[AUDIO FROM CHINATOWN POST OFFICE]

Rosario Dawson: You’re hearing sounds from the post office at 6 Doyers Street in New York’s Chinatown. In 2018 it was renamed the Mabel Lee Memorial Post Office.

[Producer: “Do you know who Mabel Lee is? Customers: No?]

This response is not uncommon. Mabel Lee is honored at this imposing stone building in her community, but as people come and go, buy their stamps, return those impulse pandemic buys… her story is relatively unknown.

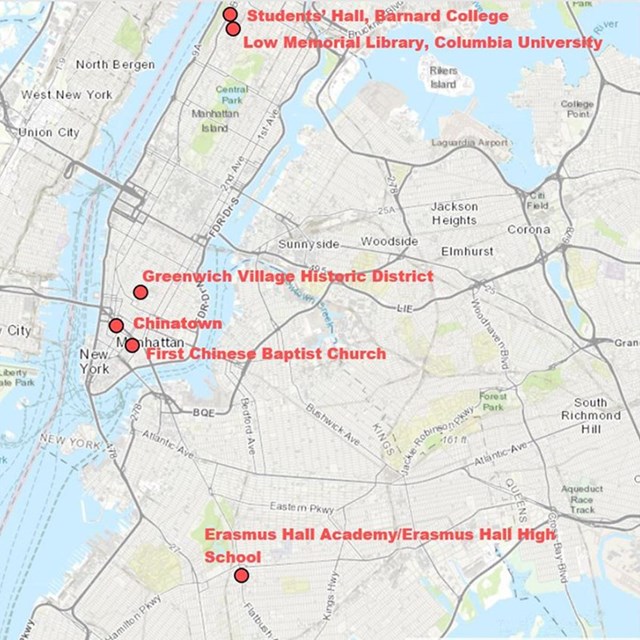

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was a prominent Chinese-American suffragist, a member of the Women's Political Equality League, and the first Chinese-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia University.

She was like so many radical, inspirational women who changed history. Women who ended up on statues, monuments and even post offices. And yet - we don’t know their stories. Or even their names.

And so many of these women who fought for American rights never got to become American citizens. While the mainstream suffrage movement declared 'Votes for Women,' women like Lee, women of color, immigrants, and Native women who were fighting for the vote, were navigating not just their gender, but also questions of immigration, race, and citizenship. Which made their fight for "Votes for Women" much more complex.

This is And Nothing Less, Episode 4: Suffrage in Translation

I’m Rosario Dawson.

Retta: And I’m Retta. [THEME]

R: “Never was justice more perfect; never was civilization higher.”

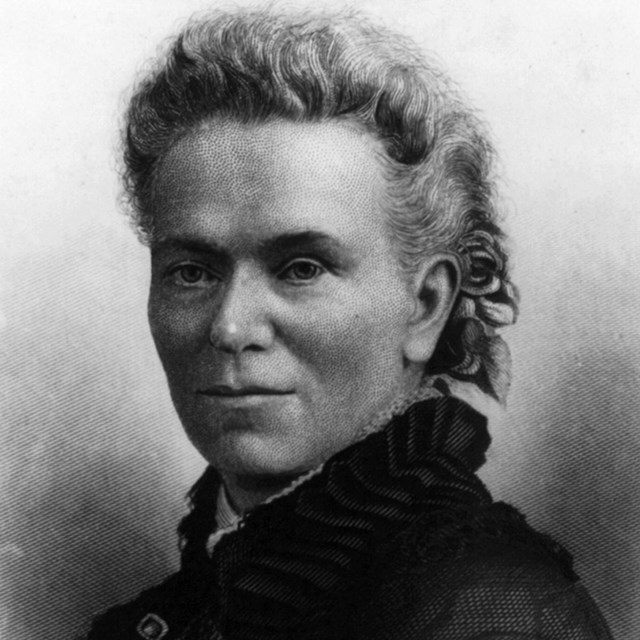

Suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage wrote that about the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, who lived in New York state.

Gage was close with the Mohawk Nation of the Iroquois. She was honorarily adopted into their Wolf Clan and invited to join their Council of Matrons. This was a decision-making body. In other words, a voting body. This was 1893 to be exact. That same year Gage was given rights and power by the Mohawk, she was arrested by her own government….for voting.

Sally Roesch Wagner is the founder and director of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation in Fayetteville, New York.

RD: She was with us in Episode 2.

R: That’s right. As she explains it, long before American women won the right to vote, they lost it.

Sally: Native American women had political voice long before white people entered this land as settlers. When the suffragists were organizing in the National Women's Suffrage Association, for example, Matilda Joslyn Gage, who is one of the leaders, said we're not asking for a new right. We're asking for the restitution of a right that our foremothers had.

R: Gage and her colleague Elizabeth Cady Stanton at the National Woman Suffrage Association -- two suffrage intellectuals -- were both interested in looking beyond their own culture for ideas and inspiration. And as New York state natives, they did not have to look far.

As they saw it, the six nations of the Iroquois had social, religious, economic and political positions that were far superior to their own.

Sally: The contrast between women in the United States, citizens in the United States and citizens of the Haudenosaunee nations. The Six Nations day and night. It’s polar opposite. Violence against women almost nonexistent before contact. And if it existed, it was dealt with very harshly. For example, when a clan mother chooses to this day, the chief that she'll sit beside and advise and she'll place him in position of authority and she'll remove him is if necessary, that's her responsibility.

R: The women basically ran the economy and were responsible for farming. Sally: They were the sacred ones to bring forth life from the land because they were the creators of life.

R: They also made the final decision about whether or not to go to war. Which makes sense when you think about men’s track record with that.

Sally: If the men want to go off to war. It can't happen if the women say no. And it's wealth, his spiritual authority, because they're the ones who have given birth to these to these men whose lives will be lost. But it's also an economic one, because if men want to go off to war and there aren’t any food, there aren’t any moccasins, they aren’t going to get very far.

R: Women like Stanton and Gage even admired the freedom Native clothing gave women.

Sally: White women were drinking arsenic to have whiter skin. They were afraid to go outside without wearing hats and gloves and being totally protected because their skin might get a little bit brown. They corseted to 18-inch waist. By the time you got to be my age, you couldn't stand up straight without your corset because your muscles had atrophied. You'd started corsets when you were 10. And the clothing, 20 pounds of clothing suspended from this tiny, encased, corseted waist meant mobility was not easy. And of course, that affected every part of your life.

R: It wasn’t just the corsets that were confining upper class women during Gage and Stanton’s time. The laws were also constraining. Especially for married women. They were basically invisible in the eyes of the law. When a woman married in the early 19th century, everything she owned became her husband’s property. Everything she earned, became her husband’s wages. Her children belonged to their father. She had no legal protections against abuse or even rape at the hands of her husband. Given all this, it’s easy to understand why a vote would seem so far-fetched. That is, unless, you saw that there was another way to live.

Sally: There are specific suffragists across the United States, women being influenced by seeing the position of Native women, knowing about it through personal contact, knowing about it through the newspapers, knowing about it through books, knowing about it through just the history as people knew the history at that time. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was one of the suffragists that picked up that research and and ran with it. She begins to study the prehistoric matriarchy, as in the 1880s, 90s when this information becomes widespread. It was part of the strategy saying, look, we're told that our position of inferiority to men and being under the authority of men, being subordinate to men, we're told that that's God ordained. So they needed something that would say, look, it is neither God or ordained nor biologically determined.

They don't want to go to hell. If you had if you demand the right to vote, you're going up against God. That's what they were confronting. And so they needed proof, evidence that, look, it has not always been this way, and it is not always this way today. This is what a free woman looks like.

RD: This model of indigenous women’s rights gave suffragists a vision of something better. But according to Sally Roesch Wagner, the same cannot be said of the Native women’s experiences in 19th Century America.

Beginning in 1871, the federal government stopped signing treaties with Native nations, outlawed Native governments and placed indigenous people under legal federal wardship. As wards of the state, they were granted citizenship if they quote “adopted the habits of civilized life,” but they also experienced violent separation from their land, poverty, and permanent separation from their families.

All while this was happening, the suffrage movement was marching forward to demand a greater role in this same government that was erasing indigenous cultures. And then looking to Native people for inspiration.

That’s some pretty major irony, right?

Sally: The irony is that at the same time that United States citizens, women, were taking inspiration and learning, this is what we should expect from Native women, the “Christianize and civilize” policy of the United States government and churches was forcing Native women into their subordinate position of white women.

And when there was in 1878, a law in New York state attempting to force citizenship and the vote on Indian man, the chiefs, the Confederacy Grand Council met at Onondaga as they've been meeting since before Columbus and continue to meet today to make decisions. And their decision was, no, we will not accept citizenship in the United States. Matilda Joslyn Gage at that time was editing a women's suffrage paper and she wrote an editorial in support of the decision of the Chiefs. And then she goes on to learn strategy from them. She's says you know, the chiefs went to the White House from all over the the land. They converged on the White House last New Year's, and that's when the president would be receiving people. And they converge on the White House and they all present their calling cards, on the back of each one of them is a broken treaty.

RD: A calling card as in a visiting card. Something you left when you made a call on someone. And they leave these cards for the president. And she said, you know, maybe we should adopt a strategy like that.

RD: Here things get complicated.

Native people did not want to be forced to become citizens if it meant erasing their own culture. But unless they were citizens, they couldn’t vote in U.S. elections. And without a vote, Native communities couldn’t change the discriminatory policies affecting their way of life

And so many made the choice to reject voting rights, at least at first.

Sally: For some women, some indigenous women have talked about how because the Indian Citizenship Act wasn't passed until 1924, 1920 didn't mean anything to them. Those who became United States citizens in cases forced to become United States citizens. But once you're citizens, you want a place at the table, you want to vote.

Looking back at the history of suffrage and Native Americans in the 19th and early 20th century shows how acutely voting is linked to citizenship. No citizenship, no vote. This is also true for African Americans and immigrants coming to the United States. They fought for the right to vote and for citizenship. But at various points in history, not being citizens excluded them from ever entering a voting booth.

That’s next, on And Nothing Less.

---

BREAK/SHORTIE

---

R: At the corner of Lincoln and San Francisco in old Santa Fe plaza stands the Palace of the Governors. Flanked by Spanish colonial and Pueblo style buildings, this has been the center of life in the New Mexico capital for hundreds of years. There’s also a Haagen-Dazs up the street.

RD: And one afternoon in October, 1915, one hundred and fifty suffragists filled up the plaza before starting their route. They’d head south to the capitol building, back across the plaza and then north to the federal building.

Cathleen: It was organized by suffragists in New Mexico who tended to be Anglo and Hispanic women.

RD: Cathleen Cahill is a Penn State University professor and the author of Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement.

Some marched on foot, but as we’re well into the 20th century, many rode in cars, decorated for the occasion.

Women like Mrs. Trinidad Cabeza de Baca, whose family owned one of the first cars in the city. And women from powerful Hispanic families in the state.

Cathleen: These are women who had been in different kinds of women's clubs and they're sort of an umbrella organization of the New Mexico Women's Club organization. And many of them start pushing for suffrage for similar reasons for women across the country. They are concerned what's often called social housekeeping issues. So questions of women's labor and children's labor laws, health issues, and they're working in their communities and sort of seeing some of these concerns that face particularly women and children and want to be able to participate in government, government to address them. And this is true for both the Hispanic women and the Anglo women.

RD: But some of these suffragists did have some other concerns. The western U.S. came with its own complicated history. So, Hispanic suffragists faced unique challenges. They were immigrants. Some weren’t white. Some weren’t citizens. And they didn’t all speak English. The suffragists of New Mexico were living in an area that had only become a state three years earlier. If they were going to get the political and social power they wanted, they needed to make the national suffrage movement and the federal government listen.

During that October 1915 parade, the suffragists of Santa Fe were also due for a visit from Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party. The NWP was focused on amending the U.S. constitution to secure women’s right to vote. They needed New Mexico. And because of the way New Mexico’s state constitution was written in 1912, New Mexican suffragists needed the National Woman’s Party.

R: Why?

[music]

RD: Well it’s because of the unique way in which New Mexico’s state constitution was written. The women of the state knew they would have a tough time getting a suffrage amendment passed. A federal amendment was their only hope.

Cathleen: Many other Western states have granted women's suffrage. There have been campaigns in those states that have been successful. So New Mexico actually ultimately is really the only state in the West that doesn't grant women's suffrage at the state level before 1920, in large part because of this constitutional issue that the constitution was very hard to amend.

RD: It was hard to amend precisely to protect religious and language freedom. In other words, to protect Spanish-speaking Catholics.

Cathleen: Nina Otero Warren, who's one of the women that I look closely at, and also Aurora Lázaro. Both of those women are in Santa Fe, are related to powerful male politicians who are right in the midst of these constitutional debates and are on the committees writing parts of the constitution. And they are all working to try to protect Spanish language. The federal legislation, the enabling act that Congress passes to allow New Mexico to send their tentative constitution to Congress says that it should be, it should specify English only. And the folks making the Constitution refuse that and actually put in some really strong protections for Spanish language rights and for religious affiliation and for the suffrage movement. What this means is they actually make the constitution, the state constitution extremely hard to amend. And so the women working for suffrage rights in New Mexico are going to find it really hard to change the state constitution.

RD: Suffragists like Otero-Warren and Lazaro were working hard for the right to vote to improve the lives of women and children. In that sense they were no different than their fellow activists across the country. But, in addition to wanting to have a greater voice in laws and policies, they also insisted on protecting their Spanish language at a time when many other Americans were happy to do away with it.

R: So what happened with the march?

RD: Well it ended at the house of New Mexico Senator Thomas Catron. This was a man notoriously against women voting. In a 1917 article on suffrage that he introduced to the Senate, Catron wrote that women voting was quote “detrimental to the human race,” and called the feminist an “avowed enemy to the home.”

While in front of his house, four speeches were given asking the Senator to support the federal amendment. But, perhaps unsurprisingly, he was unconvinced. He listened and then reminded the marchers of man’s god-given dominion over women.

But the Hispanic suffragists of New Mexico had made their mark on the National Woman’s Party. Otero-Warren became the group’s state leader the following year. And eventually, the first Latina to run for Congress.

And she’d be able to vote in 1920 when New Mexico became the 32nd state to ratify the 19th amendment.

[Music]

R: So I think it’s time to get back to Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.

Let’s go to New York, 1912. She’s sixteen and living in Chinatown. She’d been in New York since she came to the US from Canton - now Guangzhou - when she was about five years old. Mabel’s parents were teachers in a Baptist church and were raising their daughter to be a thoroughly modern woman. She was learning Chinese classics, but she also went to a New York public school. And she was also a feminist.

RD: At the corner of 7th Ave and 47th Street in Manhattan, not far from Times Square, young Chinese Americans like Mabel and prominent Chinatown community members met with suffrage leaders at the Peking Restaurant to talk about women’s rights ahead of a massive parade being planned down 5th avenue. Women like Anna Howard Shaw, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association and Harriet Laidlow, a New York city suffragist. And Chinese community leaders like Mabel Lee and her parents, teachers, merchants and missionaries. All immigrants to the U.S. None eligible to vote. And Mabel stood out.

Cathleen: She was apparently a very charismatic speaker and really could captivate an audience.

And they really take a liking to her. And so they ask her if she will lead or ride in the opening There's a group of about 50 mounted riders who are going to open this massive parade. There's thousands of women that will be in it. And they ask Mabel Lee to be one of those riders at the at the beginning of the parade.

RD: In addition to winning over suffrage leadership, Mabel Lee also talked to them about the sexism she suffered and racial prejudice.

At that point in her life she was only sixteen and had recently been accepted to Barnard College. Due to very harsh immigration laws, she was one of the very few Chinese women who lived in the U.S. in the early twentieth century

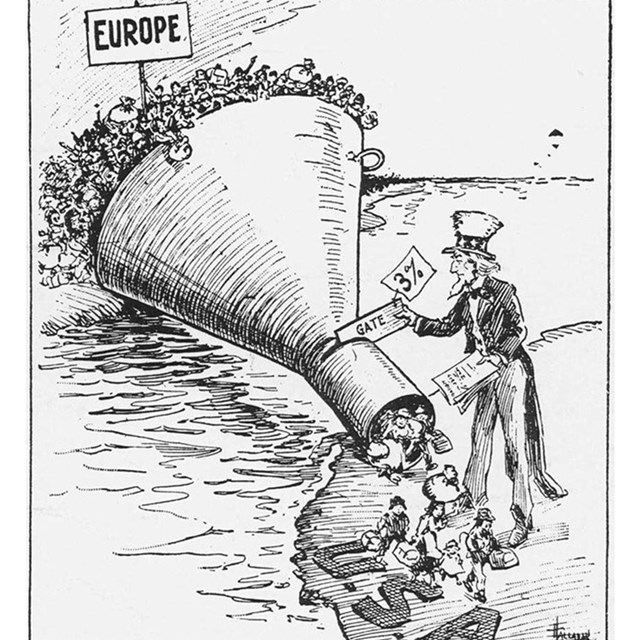

Cathleen: In 1882, the United States passes what becomes known as the Chinese Exclusion Acts, which basically say that the number of people from China who are going to be allowed to immigrate is extremely small. There are a few small exceptions, but basically they're cutting off all immigrant laborers from China. And that's the vast majority of people who want to come to the United States, mostly Chinese men.

Mabel's mother is allowed to come because she is a teacher. She's going to be working in the mission with him. And teachers are one of the exemptions to the Chinese exclusion acts. And Mabel is her daughter is able to come.

So the Chinese exclusion acts cuts off this ability for Chinese laborers to emigrate. It also states that immigrants from China cannot become naturalized citizens no matter what their class status or their immigration status.

R: Because they could not become citizens, people like the Lees were not able to vote. And yet, many women like Mabel were passionate about suffrage. You have to wonder why?

The reasons for this, according to Cathleen Cahill, are more political than they are personal. You have to look at what was going on around the world and back home in China.

Messages of the Chinese revolution included women’s rights and equal education.

Cathleen: Their vision of the fight for suffrage is broader than just the United States. They're looking internationally and they're very involved with the discussions around the Chinese revolution of 1911. And so they're thinking about the building of a new Chinese republic.

News of the Chinese revolution comes to the United States. Newspapers cover it pretty heavily. There are lots of stories about the Chinese women who are involved in the revolution. There's actually a woman's volunteer military unit that gets a lot of coverage. And there's a great deal of interest in this. And then with the establishment of that Chinese republic, what's reported in the U.S. is that the Chinese have enfranchised their women.

So for white suffragists, this doesn't fit with all of these American stereotypes about China being this very backwards country, so backwards that its people can't become citizens of the US. And so American white American suffragists want to know more. So they reach out to Chinese women in the different Chinatowns in their communities and ask them what's going on and invite them to meetings, to suffrage meetings. And those Chinese women are very willing to go because it gives them this audience of up, in some cases, really powerful national leaders. And white suffrage leaders are curious and want to use the idea of Chinese suffragists to kind of shame American men. Look at this country that we think it's so backwards, but they've enfranchised women. You know, that's flipping everything we think about who's the civilized country on its head. Whereas the Chinese women are excited to have this audience and they use their platform to talk about the issues that they're concerned with, particularly education for Chinese children, the prejudice that they face. And, of course, the immigration and citizenship policies of the US.

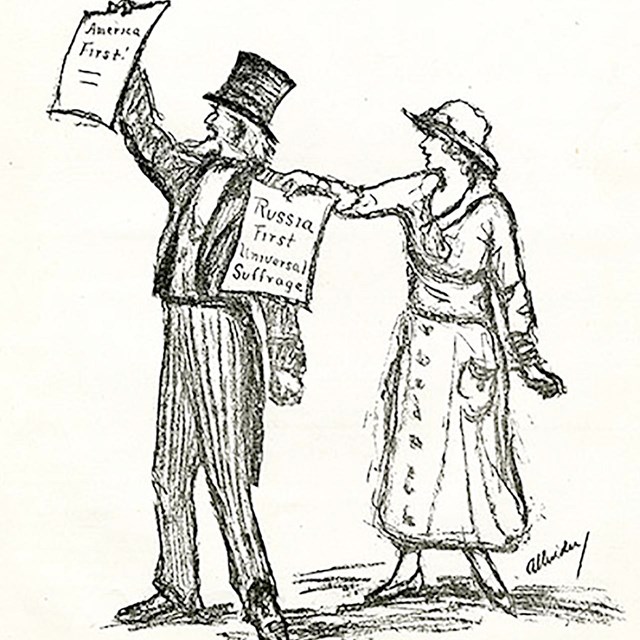

R: The ways in which the Chinese and white suffragists both used their platform for their own causes was very much on display at the 1912 5th Avenue parade. Mabel, her mother and other Chinatown women proudly carried an American flag as well as a sign that read “Light from China.” Anna Howard Shaw had her own banner. It read “NAWSA Catching Up With China.” In other words -- when it comes to voting rights, who are we calling backwards?

[pause]

RD: That fall Mabel Lee went to Barnard. And she continued to promote women in both the United States and China.

Cathleen: She talks to both white American suffragists, but she's also directing her arguments for women's suffrage to the Chinese Student Association and arguing that as they build their new nation, they can't they can't leave women out. And in fact, she'll point to Britain and the United States in the suffrage movements there and say, look, these countries left women out. And so now they're trying to sort of bring them in. And it's a patch job. Right. We're building a new nation. We can do it from the ground up.

RD: When New York women won the right to vote in 1917, Mabel was not a citizen. When the country guaranteed women's right to vote in 1920, she was not a citizen. But a year later, she became a PhD in economics from Columbia University. She was the first Chinese woman to do so.

R: Women like Mabel Lee didn’t become citizens until 1943 when the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed. Over two decades later, we don’t know if Mabel Lee ever became a citizen or if she ever reached the ballot box, but we do know she helped us get there.

[fade up postal worker who knew Mabel Lee]

[MUSIC]

RD: Next time on “And Nothing Less,”... the revolution continues, and it’s on a trip around the world.

Dubois: So in the early 20th century, the British suffrage movement takes off like a rocket.

It generates a militant wing of the suffrage movement which cannot find a place for itself in the suffrage mainstream.

RD: I’m Rosario Dawson.

R: And I’m Retta. Thanks for listening

[CREDITS]

This was And Nothing Less, from the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission and PRX. This podcast was envisioned by W-S-C-C Executive Director Anna Laymon with support from Kelsey Millay.

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Adelina "Nina" Otero-Warren

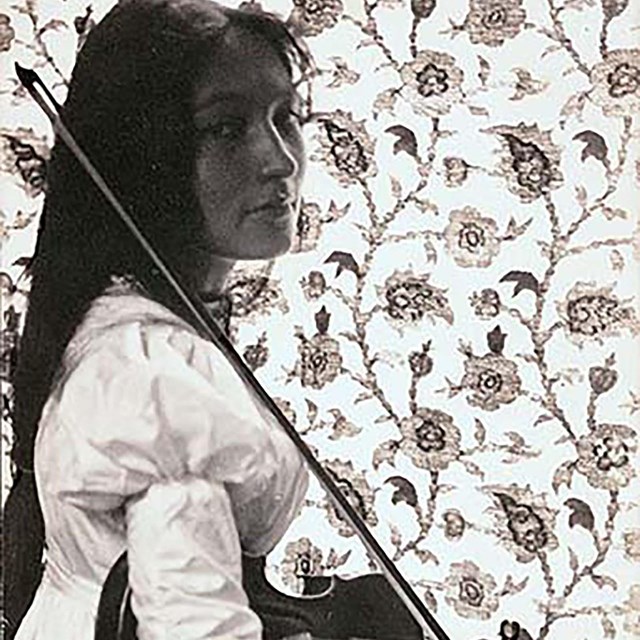

Adelina "Nina" Otero-Warren Zitkala-Ša

Zitkala-Ša Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw

Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw The Places of Dr. Mabel Lee

The Places of Dr. Mabel Lee New York CityChinatown

New York CityChinatown New YorkAllegany Council House

New YorkAllegany Council House PlacesBelmont-Paul Women's Equality NM

PlacesBelmont-Paul Women's Equality NM The Places of Nina Otero-Warren

The Places of Nina Otero-Warren New MexicoPalace of the Governors

New MexicoPalace of the Governors Woman Suffrage in the West

Woman Suffrage in the West The Necessity of Other Social Movements

The Necessity of Other Social Movements International Connections to US Suffrage

International Connections to US Suffrage Closing The Door on Immigration

Closing The Door on Immigration Indian Children Forced to Assimilate

Indian Children Forced to Assimilate