Last updated: February 20, 2025

Person

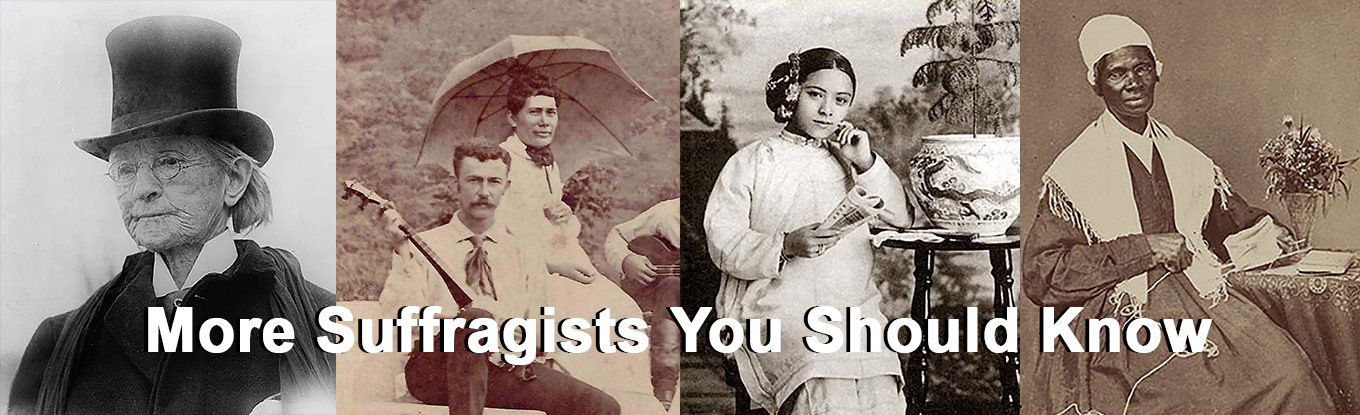

Reverend Dr. Anna Howard Shaw

Courtesy the Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016844732/

Anna Howard Shaw was born in northern England in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1847. At the age of four, her family left England and immigrated to the United States. In their new country, the Shaws made several moves. After settling in the bustling port city of New Bedford, Massachusetts, they uprooted again, this time to the industrial city of Lawrence, Massachusetts.[1] A few years later, the family at last settled on a farm in rural Michigan. Deciding she did not want to continue working on the farm, Shaw pursued teaching and then worked as a seamstress. None of these vocations really suited Shaw, but they would shape her for life. These experiences served as the foundation for Shaw’s insistence on tackling the problems of working and indigent women along with the cause of suffrage.

In her mid-twenties, Shaw enrolled in Albion College in Albion, Michigan. She then returned to Massachusetts and enrolled in the School of Theology at Boston University. After becoming a Methodist minister, Shaw worked at the Dennis Union Church in Dennis, MA. But she was not content to stay out of the city of Boston. She started commuting back in from the Cape Cod area and pursued a medical degree at Boston University while continuing her ministry.[2] She was only the second woman to graduate from BU’s School of Theology and the first to be ordained as a Methodist minister. She received her medical degree in 1886. Still, Shaw did not spend much time working in either field. Called to do more overtly political work, Shaw decided not to minister or heal one-on-one and left to speak to a larger base.

By the mid-1880s, Shaw was establishing herself as an advocate for temperance, a cause she took in part because of her time doing medical work in Boston. She first worked as a paid lecturer with the Massachusetts Women Suffrage Association, a position she secured through her connections with the prominent suffragist Lucy Stone. Moving up the ranks, Shaw was subsequently hired to work with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, or WCTU, a national organization working against the consumption of alcohol. For Shaw, temperance and women’s suffrage were not mutually exclusive causes. As Chair of the Franchise Department of the WCTU, Shaw traveled extensively to promote women’s voting rights. The WCTU believed that, with access to the ballot, women would vote for candidates who supported temperance. As she rose to prominence on the lecture circuit, Shaw was elected president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1904.

Shaw was known as a fierce advocate for working class women. Yet her Progressive politics with regards to suffrage and labor must be understood within a larger context. As Shaw traveled the country, she also espoused nativist, or anti-immigrant ideas. Under her leadership, NAWSA was known to be a hostile organization to African American women and other minorities. Shaw’s exclusionary politics were not unique. Unfortunately, they were too often mirrored in the practices and policies of NAWSA and other pro-suffrage groups for women.[2] This, too, is part of the legacy of Shaw’s ministry and speaking career.

In her final years, Shaw focused on another form of national service, becoming part of the Woman's Committee of the Council of National Defence during World War I. This would earn her widespread acclaim and praise from President Woodrow Wilson. Still, contemporaries more likely knew her for her speeches on suffrage and temperance: Shaw is estimated to have delivered over 10,000 in her career. In July 1919, less than a month after the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed by Congress and sent to the states for ratification, Shaw died. She did not live to see it become law. In 1897, Shaw had said, “The millennium may not come when women vote, but it will never come, until they do.”[4] At her bedside when she died was Lucy Elmina Anthony, Shaw’s partner of 30 years and niece of Susan B. Anthony.

Though she served as a leader during critical years of the fight for suffrage, Shaw is not as well-known as some of her peers, such as Susan B. Anthony, even as they often circulated in the same networks. Some honor her day of birth, February 14th, as an alternative to Valentine’s Day.

[1] New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park

[2] Cape Cod National Seashore

[3] Paul Dreier, “Heroes but Not Saints: How should we judge reformers and radicals who were also racists?” Public Seminar September 13, 2018.

[4] Cited in Winnifred Harper Cooley, The New Woman (1904).

Sara Egge, “How Midwestern Suffragists Won the Vote by Attacking Immigrants,” Smithsonian Magazine.

Barbara R. Finn, “Anna Howard Shaw and Women’s Work,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies Vol. 4, No.3 (Autumn 1979): 21-25.

Trisha Franzen, Anna Howard Shaw: The Work of Woman Suffrage (2014)

Anna Howard Shaw, The Story of a Pioneer (1915)