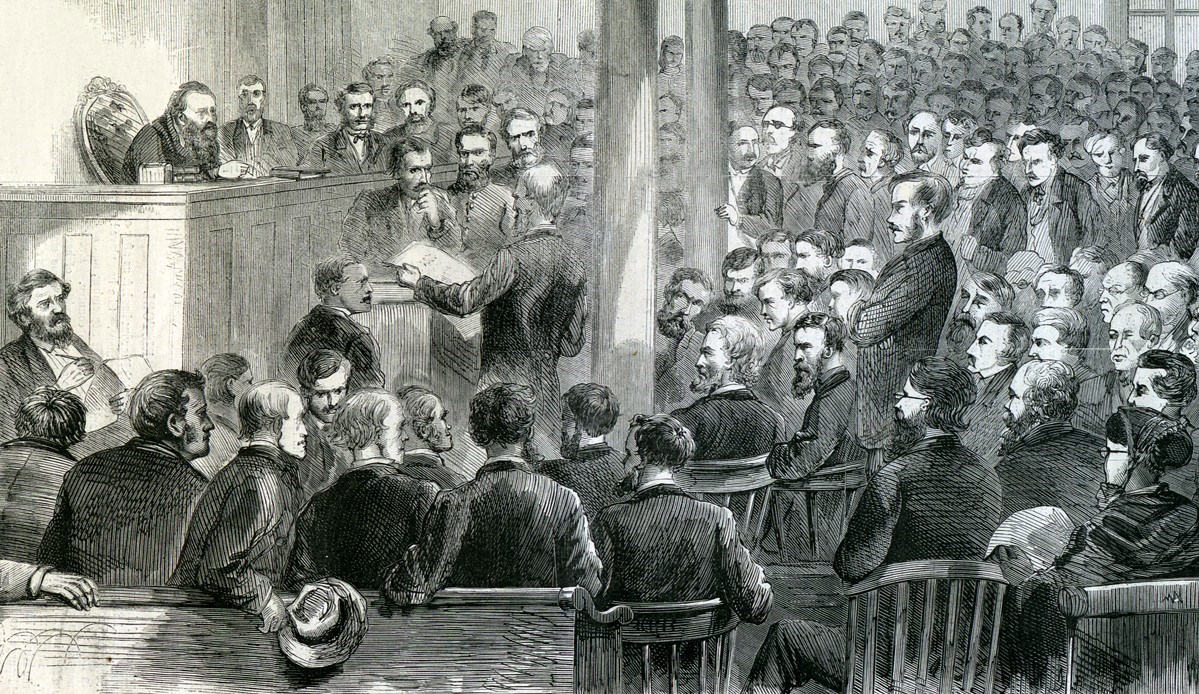

Harper’s Weekly, June 1, 1867 Thirty-seven other treason indictments were dropped at this time as well, including the pending litigation against Robert E. Lee.1 All former Confederates not under those indictments had been mass pardoned by President Andrew Johnson the previous Christmas Day, and the February nolle proesqui order drew to a quiet conclusion any threat of legal action against anyone for their participation in the war against the United States. Many factors aside from the merits of the case itself prompted the federal government to abandon prosecuting Davis. Delays had dragged out the trial process for years, including the reluctance of one of the two trial judges – Chief Justice Salmon Chase – to participate and his lengthy absence to preside over the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson. Chase’s aspirations to run for president himself in the next election cycle and his private consultations with Davis’ legal team also muddied the function of the case, as did the hyper-partisan attitudes of the judge who co-presided, radical Republican John C. Underwood. The unpredictability of a Richmond jury (which excluded former Confederates from serving and was thus composed of wartime Unionists and African Americans) and a last-ditch effort to bypass the jury by having the case dismissed on unrelated constitutional grounds made the case, in the estimation of prosecutors, too complex and politically charged to be worth pursuing. For his part, Jefferson Davis was apparently eager to defend himself in court. He intended to argue that secession had been legal in the hopes of publicly (and legally) vindicating himself and the entire Confederate movement. His counsel, however, prioritized securing his client’s freedom over the larger question of settling secession’s legality, and was successful in concluding Davis’ case without having to place the question of secession before a Richmond jury. The question of secession’s lawfulness was instead ruled upon by the United States Supreme Court in a less sensational case just two months later. Texas v. White, in April 1869, stated succinctly that the Confederacy’s secession had been “absolutely null.” Williams v. Bruffy, an 1877 case, elaborated further on secession’s illegality with much more a thorough explanation by the court of the legal reasoning involved. These rulings stand as the current authority on the status of secession in American law.2 1 John Reeves, The Lost Indictment of Robert E. Lee: The Forgotten Case Against an American Icon (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), 63-64. 2 see Cynthia Nicoletti, Secession on Trial: The Treason Prosecution of Jefferson Davis (Cambridge University Press, 2017) for the definitive account of the Davis trial. |

Last updated: August 30, 2023