I’m laying face down in the top of the Brooks River when it occurs to me that, in this position, I may appeal to a bear’s curiosity. The water is clear as day but floating on my belly I can’t see if any investigative bears are on the shore.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

The white noise of the river fills my ears but I can still hear the squeaky stutter of a Bald Eagle overhead. Facedown I inspect the details of this environment but the bird sees the big picture: two massive Alaskan lakes connected by a couple miles of twisting river. Katmai National Park protects this twisting river and all its inhabitants. Today, I’m swimming the length of it hoping to glimpse a few of those species.

My back to the sky and arms outstretched, the gravel passes beneath me as the lake becomes river and the current comes into itself. I’m still taking in the beauty of the light beaming through the water when I spot a fish. I back stroke to get a better look but it’s too late the river has me now and I face back into the downstream to see a school of fish wriggling against the current below me. They’re so close. I reach down to touch one and in an instant it shoots away, my hand feels only pebbles from the river bottom.

Photo by D. Lombardi

Photo by D. Lombardi

I float on, giddy to be a guest in a world that is not my own. To check for bears without standing I strain the cold muscles in my back to lift one side of my mask toward the banks then plop my face back into the water to see what I’ve missed.

Every boulder in the streambed has at least a few fish treading the slack water behind it and I’m spinning in circles trying to see them all. I come to a place where the river pushes fast around scattered boulders and I turn to float feet first. I shoot past fish as the current pulls me around rocks. In an effort to take a longer look I grab the next boulder as I go by. It almost works but my hand slips and I only get a fleeting glimpse of a few heavy scaled fish as I go by.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

I grab again on the next rock and this time I’m able to hold. Now I can feel the true force of the water as it crushes around me. The current pushes cold into my wetsuit but I hold tight. I am hanging in the water next to a small school of fish.

These are Longnose suckers. The only species of sucker found in Alaska. They sometimes grow close to two feet long but these are not trophy fish. No angler poses for pictures with a Longnose sucker on his line. Regardless, I’m enchanted watching them suck up little bugs from the rocks. They have no teeth in their jaws and their lips form a round vacuum on the bottom of their heads. Farther back in their throats there are pharyngeal teeth that they press food against.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

They aren’t the most charismatic fish in the river but suckers add to the diversity and resiliency of the ecosystem. Eagles, osprey and otters eat Longnose suckers and other fish and ducks prey on the juveniles. Before long they swim off and I release myself back into the current.

Fish like the Arctic Char and the Dolly Varden Trout may also make this river home even though I haven’t seen any. It’s not even all that unlikely for Northern Pike (Esox lucius) and Lake Trout to use this river on occasion. Rather than one particular species this diversity is what the National Park Service seeks to preserve.

I most desire to swim with the Arctic Grayling but I’m least able to get a good view of them. Growing up in the lower forty-eight, where Grayling have largely been extirpated, I see them as rare and special fish even though they’re plentiful here in Alaska. When I spot one I hold perfectly still hoping not to spook it as I float by. Its long elegant dorsal fin flexes like a wisp of purple smoke as it rises to the surface of the water for an insect.

Like many of the other fish in the Brooks River, Grayling can live for several decades and have widely varied and unique life histories, the specifics of which are still mostly unknown. Across their range some populations of Grayling are fluvial, living and spawning in rivers. Other populations are lacustrine and spend their lives in lakes. Still others live in lakes but spawn in rivers and streams.

Like caribou or bears these animals migrate and travel throughout their lives in ways that are unique to each population and even to each individual. Fish in any given ecosystem find a system of survival that works best in that place. Katmai isn’t a National Park just to preserve the animals but also the natural processes, like migration, that make the animals wild.

The Brooks River bends back on itself constantly and I follow the outer edges where the current is strongest and the water is deepest. Here is where I find the big Rainbow Trout weaving through the branches of a birch tree that fell in with an eroding bank last summer. At the last second I’m able to grab a red-barked branch. From there I climb upstream, branch-by-branch until I’m suspended in the stream parallel with the speckled and multicolored monster of a fish. I think it might be as long as my leg and maybe just as fat too.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

This is the trophy fish of the Brooks River. Anglers come from around the globe to lure these guys into their hands with artificial flies – but only for a few moments - Rainbows are all catch-and-release on the Brooks River. I’ve been watching these fish swim from the banks for the past month but ever since the river opened to fishing I’ve been seeing one or two dead rainbows floating down stream each day. It can be a tremendous thrill to spend twenty minutes or more reeling in one of these animals but it can exhaust the fish, perhaps to the point of death. One purpose of a national park is to allow for recreational uses so long as all is left unimpaired for future generations.

I continue downstream gawking in wonder at all the life passing around me. I’m nearing the end of the river where, just the other day, I saw an Arctic Lamprey swimming in the shallows. Muddy black and serpentine it was thicker and longer than a pencil and sometimes they get much bigger than that. Lampreys are parasitic and look like leeches but they maintain as complex and dramatic a lifecycle as any other fish in this river. Some are anadromous and when they spawn in freshwater streams both the male and female build a nest for their eggs together. This is just another strand in an elaborate web of animals that call the Brooks River home.

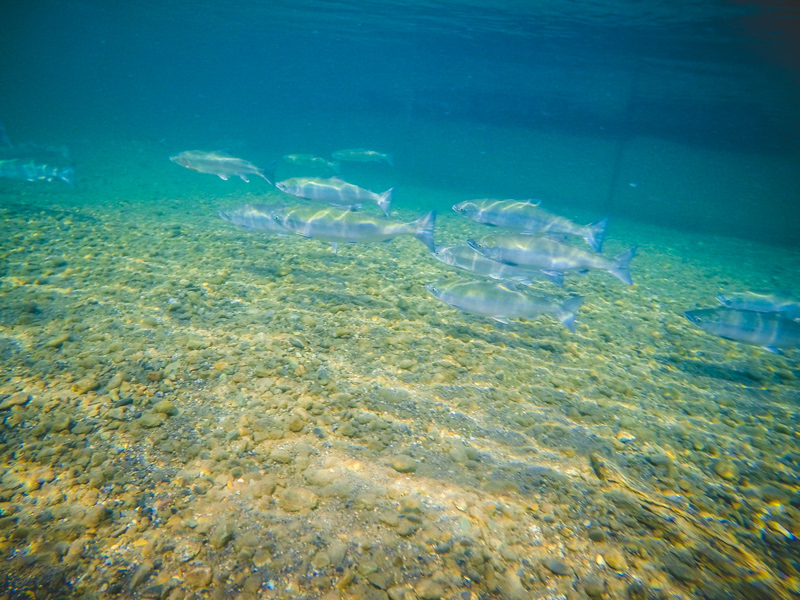

I float slowly past the boundary of the river into Naknek Lake. I’m about to swim to shore when I see flashes of silver through the blue haze of the water. The flashes are fat shiny fish in a massive school that parts and rejoins as I float through it. For a moment I’m confused then I understand all at once. After two years in the ocean these are Sockeye Salmon returning to their natal streams to spawn and die.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

Photo by D. Lombardi.

This is the keystone of Katmai. These fish bring a bounty of nutrition from the ocean into the interior feeding everything from other fish, birds and bears, to the trees along the shore. Remains of salmon left by bears on the shore soak nitrogen into the soil for trees and grasses to absorb. I wonder what the Brooks River would look like without the salmon. This annual migration is one of nature’s greatest events and perhaps the most magnificent of all the natural processes preserved by Katmai National Park.