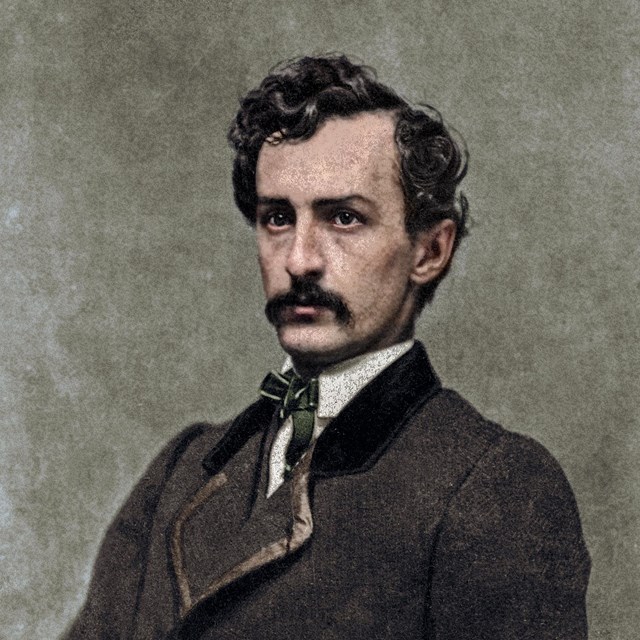

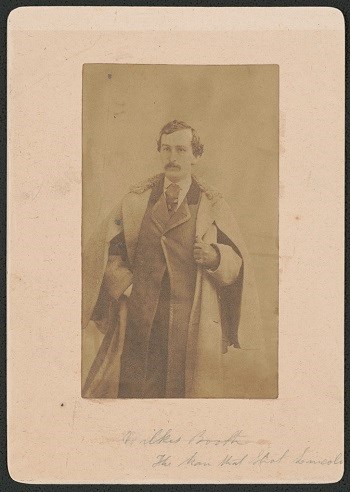

NPS Photo From April 16 – 20, 1865, the two fugitives hid in a pine thicket in southern Maryland, with food, water and newspapers supplied by Confederate agent Thomas Jones. Booth was anxious to read any news of the assassination and his plot to take down the United States government. Booth was certain that he would be heralded as a hero by many. Like any actor, he looked forward to reading the “reviews” of the events of April 14, 1865, in which he had played a leading role. Jones later recalled Booth’s insatiable interest in how he was being judged for his act. He wrote that Booth “never tired of the newspapers. And there – surrounded by the sighing pines, he read the world’s condemnation of his deed and the price that was offered for his life.”

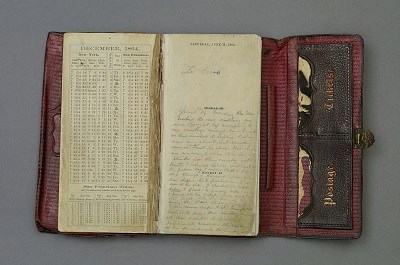

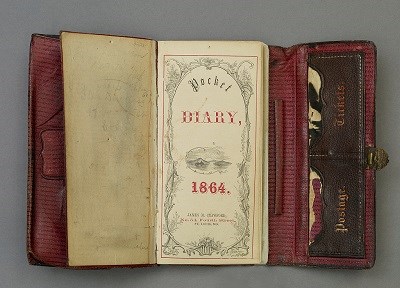

Library of Congress The diary is described in the museum collection at Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site as “a small book, which was actually an 1864 appointment book kept as a diary, found on the body of John Wilkes Booth on April 26, 1865. The datebook was printed and sold by a St. Louis stationer named James M. Crawford. The book measured 6 by 3 1/2 inches and pictures of 5 women were found in the diary pockets. Booth's entries in the diary were probably written between April 17 and April 22, 1865." The diary is now on display in the museum at Ford's Theatre National Historic Site, along with many other artifacts presented as evidence at the trial of the conspirators in June, 1865. Booth wrote two entries in the datebook. The first was likely written between April 17-20 in the pine thicket, while Booth dated the second entry as April 21. A full transcription of Booth's handwritten text in the diary is as follows:

Ford's Theatre National Historic Site Museum Collection [FOTH 3221] First Entry:[Page 1] April 14 Friday, The Ides. Until today nothing was even thought of sacrificing to our country’s wrongs. For six months we had worked to capture. But our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done. But its failure was owing to others, who did not strike for their country with a heart. I struck boldly and not as the papers say. I walked with a firm step through a thousand of his friends, was stopped, but pushed on. A colonel was at his side. I shouted Sic Semper before I fired. In jumping broke my leg. I passed all his pickets, rode sixty miles that night with the bone of my leg tearing the flesh at every jump. I can never repent it. Thought we hated to kill. Our country owed all her trouble to him, and God simply made me the instrument of his punishment. The country is not [Page 2] April 1865. what it was. This forced Union is not what I have loved “I care not what becomes of me” I have no desire to outlive my country. This night before the deed, I wrote a long article and left it for one of the editors of the National Intelligencer, in which I fully set forth our reasons for our proceedings. He or the South What was Booth saying?John Wilkes Booth's first journal entry offers insight into his plans, thoughts, and actions surrounding the events of April 14, 1865. He referenced his initial plot to kidnap President Lincoln when he stated that "for six months we had worked to capture." With the war reaching its end, though, Booth felt that more dire measures were needed. He wrote that "Our country owed all her troubles to him," as Booth believed that Lincoln was responsible for the woes of the United States and the Confederate States alike.On the afternoon of April 14, Booth wrote a letter to the editor of the National Intellingencer that he wanted the newspaper to publish. He gave the letter to a friend and fellow actor, John Matthews, who was in the production of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. Matthews was to deliver Booth's manifesto to the newspaper the next morning. However, after the assassination, Matthews opened the envelope and read what his friend had written. Fearful of the consequences should he be discovered with such a document, Matthews burned the letter. The words that Booth wrote shortly before the assassination will never be known. Additionally, Booth's first entry shows how he responded to and attempted to shape the narratives that were forming around his actions at Ford's Theatre. Booth had certainly read newspaper accounts of the assassination by this point. He knew that many people saw him shooting a defenseless President Lincoln in the back of the head as the act of a coward. The assassin wanted to correct that record to suit his own ends. He stated that he "struck boldly and not as the papers say" to influence how future generations would view what he had done. Booth also wrote exaggerations that made his story sound grander and more heroic than it really was. He did not "ride sixty miles that night," and while his broken fibula surely hurt him, it almost certainly was not "tearing the flesh at every jump." Nonetheless, these words show that John Wilkes Booth wanted to have his version of events become known and accepted.

Ford's Theatre National Historic Site Museum Collection [FOTH 3221] Second Entry:[Page 3] Friday 21. After being hunted like a dog through swamps, woods, and last night being chased by gun-boats till we I was forced to return wet cold and starving, with every man’s hand, against me. I am here in despair. And why; For doing what Brutus was honored for. What made Tell a Hero. And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew. Am looked upon as a common, cutthroat. My action was purer than either of theirs. One, hoped to be great himself. The other had not only his country's but his own wrongs to avenge. I hoped for no gains, I knew no private wrong. I struck for my country and that alone. A country groaned beneath this tyranny and prayed for this end, and yet now behold the cold hand they extend to me. God cannot pardon me if I have done wrong. Yet I cannot see any wrong except in serving a degenerate people. The little, [Page 4] the very little I left behind to clear my name, the Government will not allow to be printed. So ends all. For my country I have given up all that makes life sweet and holy, brought misery upon my family, and am sure there is no pardon in the Heaven for me since man condemns me so. I have only heard of what has been done (except what I did myself) and it fills me with horror. God try and forgive me and bless my mother. Tonight I will once more try the river with the intent to cross, though I have a greater desire and almost a mind to return to Washington and in a measure clear my name, which I feel I can do. I do not repent the blow I struck. I may before my God, but not to man. [Page 5] I think I have done well, though I am abandoned. With the curse of Cain upon me, when if the world knew my heart, that one blow would have made me great, though I did desire no greatness.Tonight I try to escape these blood hounds once more. Who, who read his fate. God's will be done.I have too great a soul to die like a criminal. O may he, may he spare me that, and let me die bravely.I bless the entire world. Have never hated or wronged anyone. This last was not a wrong. Unless God deems it so. And its with him, to damn or bless me.And for this brave boy with me, who often prays (yes, before and since) with a true and sincere heart. Was it crime in him, if so, why can he pray the same? I do not wish to shed a drop of blood, but "I must fight the course.” ‘Tis all that’s left me. What was Booth saying?By this point in his escape, John Wilkes Booth had become desperate and disgruntled. The actor who was used to living in the best hotels and eating the finest food had spent the last week living in the woods. He knew that the nation, both North and South, would not hail him as a hero for what he had done at Ford's Theatre. He knew that Federal forces were after him, that he was being "hunted like a dog." His anger reached a boiling point in this diary entry.Booth reiterated his belief that Abraham Lincoln was a tyrant and that the nation "groaned beneath this tyranny and prayed for this end." He compared himself to Brutus and to William Tell, two heroes of the past who had overthrown dictators in their nations. Booth saw himself as continuing their grand tradition of taking down rulers who had gone too far. The American people, however, did not agree. Booth lashed out in anger at the public who had rejected him and viewed him as nothing more than "a common cutthroat." He wrote that he regretted none of his actions and that he believed only God could judge him if he had done wrong. The only thing he regretted was that he had acted on behalf of "a degenerate people," those who vilified and condemned him. Booth also lashed out at the United States government, believing that it had suppressed publication of his manifesto. He did not know that his friend John Matthews had burned the letter, ensuring its contents would never be read. This final entry also provides a bit of foreshadowing for how John Wilkes Booth would meet his end. He wrote that "I have too great a soul to die like a criminal," indicating that he would not let himself be captured alive, tried, and executed for his crimes. Indeed, at the Garrett Farm on April 26, 1865, he would not be taken alive. In attempting to fight his way out of the burning tobacco barn in which he had hidden, John Wilkes Booth was shot in the neck by a Federal soldier. The assassin died a few hours later, and the pen that had written these words finally fell silent. Want to Learn More?

|

Last updated: August 14, 2025