Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress Today, Laura Keene is mostly remembered for being at Ford’s Theatre the night of the Lincoln assassination. However, history should remember her for the entire trailblazing, exciting, and fulfilling life she led as an actress, theatre manager, mother, and entrepreneurial woman. On July 20, 1826, Mary Frances Moss was born in London, England. After her husband was exiled and imprisoned for unknown reasons in Australia, Mary Frances wanted to reinvent herself. She sought an independent life that allowed her to care for herself and her two daughters. With the support and inspiration of her aunt, a retired English actress, she decided to pursue a life on stage. Acting was not a respectable profession then, though, particularly for a single mother. For this reason, as well as the need for a fresh start, she changed her identity and became known as Laura Keene. Laura Keene made her debut in England on October 8, 1851, in Richmond, on the southwest side of London. She successfully played the tragic role of Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet. Twenty days later, she made her London debut at the Theatre Royal as the leading role in The Lady of Lyons. Within a year, her outstanding presence on stage caught the attention of James Wallack, an American actor and theatre manager. He invited Laura to be the leading actress at his theatre in New York City, and she eagerly accepted the offer. While it meant leaving her children with her mother for a short time, it was an opportunity to get her family out of London, an unhealthy place for the working class.

Houghton Library Theatre Collection, Harvard University Furthermore, Laura’s success allowed her to pursue a bigger dream as an actor: to be a theatre manager. Though it was unheard of for a woman to manage a theatre, she successfully leased and opened the Charles Street Theatre in Baltimore on December 24, 1853. This act made her one of the first female theatre managers in the United States (Catherine Sinclair opened a theatre in California on the same day). Laura produced 34 plays at Charles Street. Both critics and the people praised her performances. A newspaper published the following letter about Laura: “She is an actress of unquestionable merit - the most pleasing and popular that has ever visited Baltimore. Aside from this, she is exquisitely beautiful, and sustains an unsullied reputation for all those qualities of virtue which adorn and dignify woman.” After her leasing contract ended in March of 1854, Laura moved to California. Theatres there were benefitting from the influx of money caused by the Gold Rush. Catherine Sinclair’s Metropolitan Theatre offered her a lucrative contract of $30,000 a year. While there, she met Edwin Booth. They performed many times together, although never very well. According to reviews, their styles clashed on stage. Despite this, Laura agreed to do a tour with him in Australia, where there was a boom like the Gold Rush. Many historians believe she also hoped to find her convicted husband while there and get a divorce. However, Laura never found him, and the tour was not as successful as they had hoped, either. They returned to California in March of 1855 to more misfortune. San Francisco was in the midst of a financial depression. Laura worked tirelessly to help revitalize theatre in the city before heading back to New York City. The papers recognized her work on September 18, 1855: “Besides having great tact and capacity for stage business, she [Miss Keene] devotes her whole soul and energy to the work, nor rests unsatisfied until everything is as perfect as it is possible to make it. As long as Laura Keene is there, they will see something worth going to see.”

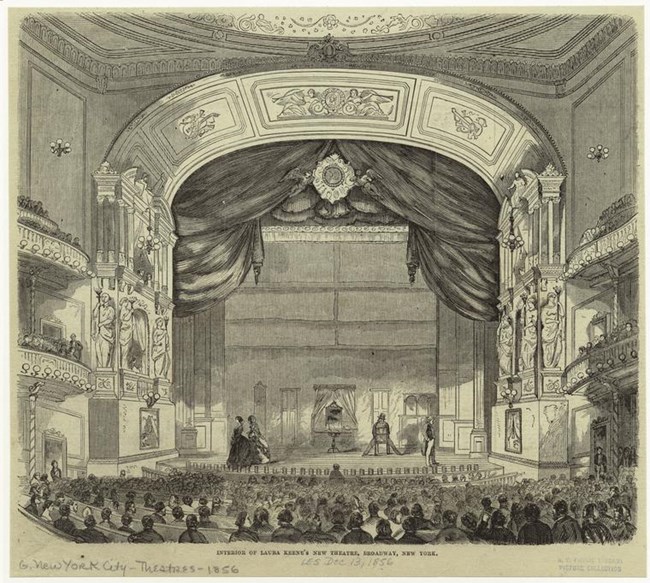

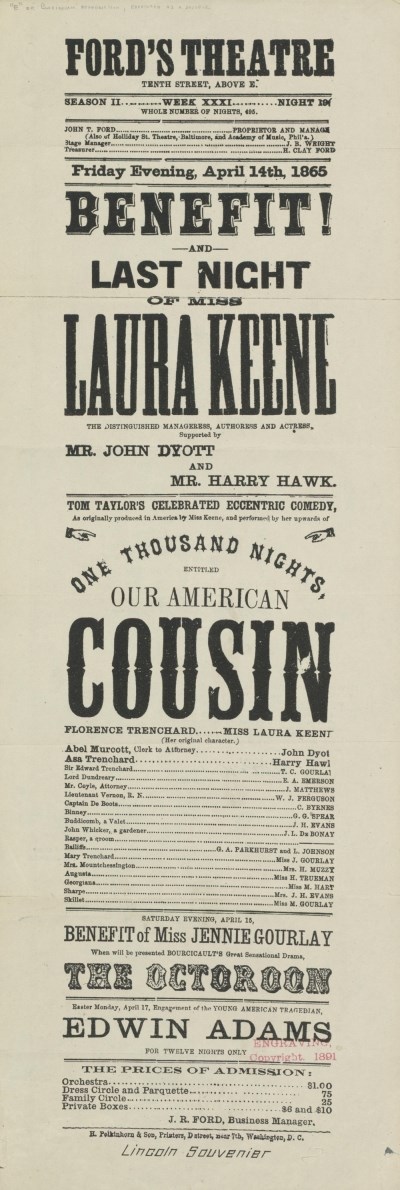

New York Public Library Laura Keene’s Theatre was extremely successful for many years to come, and Laura, herself, was the main reason behind its prosperity. She not simply run day-to-day operations. She wrote plays, helped design the sets and costumes, played the leading role in all her productions, and managed to get other famous actors of the time to be part of her stock company. Laura was more than just a theatre manager. She was a director with immense theatrical knowledge and creativity, sharp insight into an audience’s psyche, and strict punctuality. All this, paired with her excellent business skills and kind spirit, made her a force to be reckoned with in the American theatre. Many of her peers affirmed that “there never was such a stage manager as Laura Keene” and that she was “the greatest business woman [they had] ever known.” Laura was a trailblazer and greatly influenced the way theatres operated even to the present day. In 1857, her show The Elves ran for 50 performances. No show had ever lasted that long. In 1858, Laura premiered Our American Cousin and presented it for 5 months straight - a total of 145 times. In 1860, Laura broke her own record with the play The Seven Sisters. It ran for 253 consecutive nights and closed on August 10, 1861. Laura is credited for establishing the idea of a long-running show, in addition to the charity matinee. She is also credited for the revival of Shakespearean plays on the American stage, and as one of the first theatre managers to support American playwrights. While Laura was making theatrical history, theatres around her were shutting down due to the demands and climate of the Civil War. Laura was adamant to remain open, though. She felt the theatre was a place where people could get some relief from the devastating realities of a war-torn country. She believed laughter, particularly, was the best medicine for weary souls. Laura felt this way so strongly that she started a touring company to bring the joys of theatre to others. In 1862, Laura leased her theatre and left it to go on tour. She remained nonpartisan and traveled all over, from Boston to Detroit to New Orleans to Savannah.

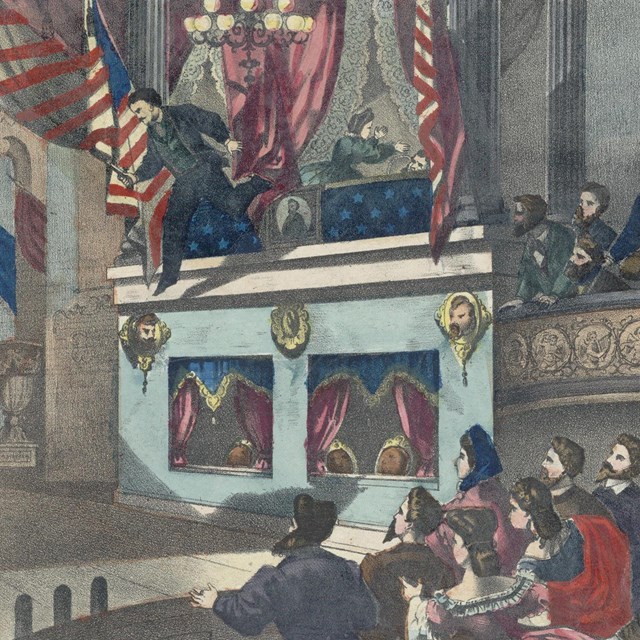

Library of Congress Some historians believe that the Lincolns decided to attend Ford’s Theatre rather than Grover’s Theatre that night because it was Laura’s final and benefit performance. Nonetheless, Laura was ecstatic that the president chose her performance. Upon the Lincolns’ late arrival, she paused the production so the orchestra could play “Hail to the Chief” as Lincoln and his party walked to the box. Eventually, everyone stopped applauding and took their seats so the play could resume. Later, a little after 10 pm and during the final third act, Laura was backstage preparing for her next scene. She heard what she thought was a gunshot caused by unruly stagehands. Then, a man she immediately recognized as John Wilkes Booth ran towards her and pushed her aside to get to the back door. As Laura got back to her feet, she heard screams and knew something was terribly wrong. She went on stage to determine the issue and saw Major Henry Rathbone covered in blood and pointing in the direction Booth had just fled. He demanded anyone to “stop that man!” Mary Lincoln was screaming and someone else was shouting, “He has shot the president!” After Laura regained her own composure, she walked to center stage to plead for order.; Her entreaty ended with the words, “For God’s sake, have presence of mind, and keep your places, and all will be well.” According to several accounts, including her own, Laura then made her way into the state box. She found Lincoln lying on the ground while three doctors tended to him and Mary Lincoln sat in shock on the sofa. According to Dr. Charles Leale, the first doctor to enter the box and treat the fallen president, Laura asked him if she could hold the president until they moved him. With his permission, she knelt and held Lincoln’s head in her lap. Only a few moments passed before they carried Lincoln outside and eventually into the Petersen House across the street. According to one historian, Laura followed alongside Mary over to the Petersen House. Another claims that Harry Ford arrived and greeted Laura with a hug while everyone was out on 10th Street. Harry later recalled that, when asked by someone in the crowd if the president was going to live, Laura exclaimed “God only knows!”

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum After the president’s death, Laura returned to the theatre and then her hotel room. There, her husband John Lutz and her daughter Emma comforted her. Despite this harrowing experience, Laura tried to return to normal and continued with her scheduled tour. She and two other actors in her company, John Dyott and Harry Hawk, were on the train heading towards their next show when police stopped them in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and arrested them. Many people suspected that other actors could have been involved in John Wilkes Booth's conspiracy. They were also witnesses to the assassination and had not obtained proper permission to leave DC. Laura was eventually released and carried on with her tour. She was hesitant to perform Our American Cousin ever again, though. She quickly encountered people eager to see her dress with President Lincoln’s blood on it. These curiosity seekers disturbed her so much that she wrapped up the dress and delivered it to Jamie Bullock, the designer. The dress stayed in his possession in Chicago until Laura’s death, upon which it was returned to her daughter, Emma. Today, only pieces of her dress still exist. Like everyone who happened to be at Ford’s Theatre that tragic night, Laura’s life was altered following it. For many years, she wrapped up her tours early to rest at her and John’s Riverside Lawn home in Acushnet, Massachusetts. Laura’s life was even more severely changed when John Lutz suddenly died in 1869. Not only did she miss him, but his death led to her financial demise. John had always protected her from those who might do her harm in the theatre business. According to Emma, Laura’s troubles began when John died, because “no one can be in front of the theatre and playing at the back, too, and the consequence is, if they have no relative in the box office, they are both mismanaged and robbed.”

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Despite it all, Laura continued to strive for success in the theatre, even if it proved unfruitful. For example, she managed the Chestnut Theatre in Philadelphia. Her competition there was none other than Edwin Booth, who managed the Walnut Theatre. The Chestnut Theatre was in the midst of a renovation, though, and the season was cut short due to financial burdens. During this time, Laura also helped Colonel T. Allston Brown, editor of the New York Clipper, develop the ingenious idea of a touring system. She selected the actors and arranged performances at southern theatres left empty following the Civil War. The idea proved successful, but it took off too quickly. The system collapsed when Laura could not keep up with the personal and financial demands. Laura’s idea may have inspired the distribution system of motion pictures. In 1872, it became clear to Laura that it was time for her to step away from the theatre. She no longer possessed the energy and star quality that made her shine on stage for so many years. Laura released some of her responsibilities to better care for herself and be with her family. She had tuberculosis and the illness was taking over. Before returning to her Riverside Lawn home, she met with her lawyers to renew the lease agreement on her theatre and arranged a rental agreement with actor E. A. Sothern for the exclusive use of Our American Cousin. She would eventually sell the play to him, including the manuscript and all rights in both the United States and Canada.

NPS/Byers Although it has taken some time for history to properly acknowledge and remember Laura Keene, that should not diminish her accomplishments or historical importance. Her unlimited talents and energy and her fierce determination to achieve her hopes and dreams made her a successful leading actress and theatre manager. She is an inspiring historical figure, and one well worth remembering at Ford’s Theatre. Want to Learn More?

|

Last updated: December 1, 2024