Probably most alarming were the reports to the Indian Agent, Edward Wynkoop from the Dog Soldier Chief, Roman Nose, that many tribes planned uprisings in the spring. These warnings would eventually bring Civil War hero, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock to Fort Larned in April of 1867 to deal with restive Cheyenne and Lakota Indians in the area. Hancock commanded the Military Department of the Missouri, which the Army created in August of 1866 to provide better protection to travelers crossing Kansas into Colorado and New Mexico.

One reason the Indians felt confident about taking on the U.S. Army is because they various traders selling them guns in violation of the Army’s General Order No. 70, which stated that only traders authorized by the Army could sell weapons to the Indians. Another “Indian problem” was getting the Dog Soldiers to vacate their hunting grounds along the Smokey Hill River to make way for the Kansas Pacific railroad. The Dog Soldiers had no intention of leaving and rumors of their attacks in the area began to circulate, though many of them untrue.

The government couldn’t ignore current Indian attacks, nor the threat of a future uprising. Congress authorized $150,000 for a spring campaign, to begin before the Indians had a chance to leave their winter camps. Gen. Hancock met the troops for his campaign at Fort Riley, which included the newly formed 7th US Cavalry under the command of George Custer. There were four companies of the 7th Cavalry and one company of the 37th Infantry from Fort Riley, as well as two more companies from the 7th, who joined them at Fort Harker. The force of almost 1400 men arrived at Fort Larned on April 7, 1867.

Before leaving Fort Leavenworth in March, Hancock had sent a letter to Indian Agents Edward Wynkoop and Jessie Leavenworth telling them that he was bringing a large force out to the plains to deal with any tribes that had been attacking travelers. Hancock was proposing to use threat to keep the tribes in line, but both these experienced Indian Agents knew that persuasion and gifts were more likely to get the Indians to cooperate. Regardless, they did get promises from the local chiefs to come to Fort Larned on April 10th for a meeting with Hancock.

On April 9th, two days after Hancock got to Fort Larned, a late spring blizzard dumped eight inches of snow in the area. This much snow made it impossible for the Indians to come to the fort for their meeting on the following day. They had also found a bison herd, which they decided to hunt to replenish their supplies instead of coming to Fort Larned.

Hancock didn’t think either of these were valid reasons to miss the meeting. At best, he thought they were stalling; at worst, they were simply ignoring him. He decided to give them another day to comply, though. By the evening of the 12th several chiefs from a nearby Cheyenne-Lakota village arrived for the meeting. Hancock decided to march to the village because he believed that not all the chiefs had come to Fort Larned. He ordered the expedition to set out the following day.

The force marched 21 miles that day and camped along the Pawnee. Hancock expected the chiefs to come to his camp the following day at 9:00. When they didn’t appear, he broke camp at 11:00 and continued towards the village.

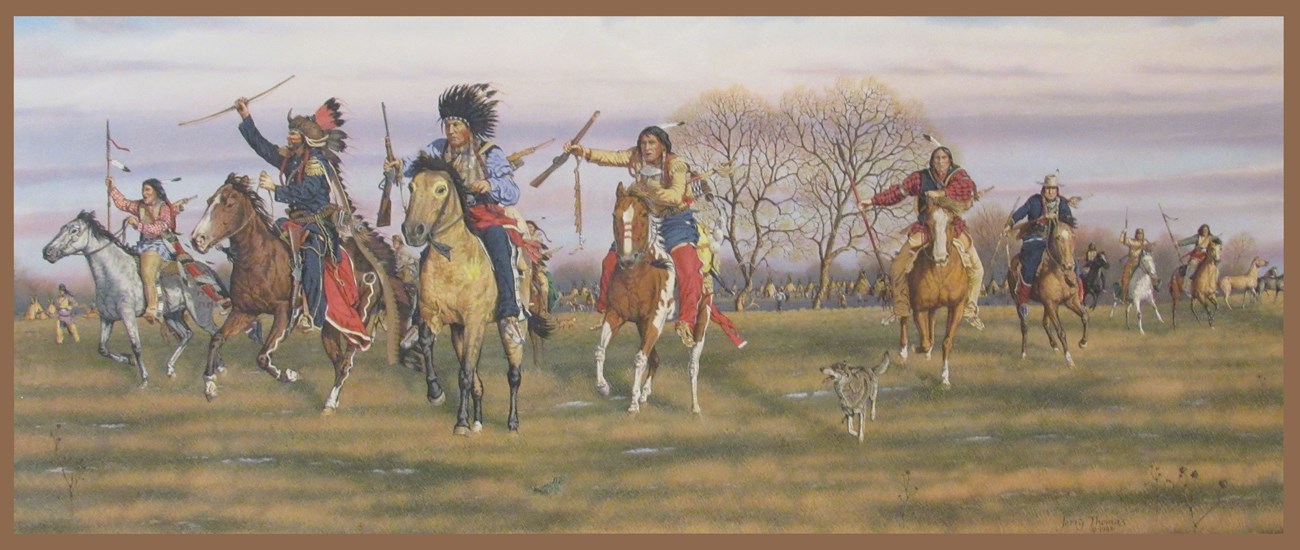

A strong force of mounted braves met Hancock’s force near the village. They were dressed in war gear and clearly ready to fight to keep the Army troops away from their women and children. Hancock was ready to attack but Indian Agent Wynkoop persuaded the general to let him to talk with Roman Nose and Bull Bear. The two chiefs wanted the soldiers to go away, afraid that any clash between the two forces would result in casualties among the women and children in the village.