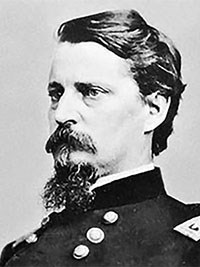

Public Domain As American society pushed west and disrupted the livelihoods of the American Indian nations on the Southern Plains, conflict was inevitable. Violence, however widespread, was typically small-scale in western Kansas prior to 1867. Much of the violence took the form of raiding along the Santa Fe Trail. In response, Fort Larned was established in 1859. Fort Larned, as part of a system of forts, allowed for a permanent military presence on the frontier aimed at converting the land from tribal to U.S. control. Following the conclusion of the Civil War, the U.S. Army and its ambitious officers turned their attention westward, where tribes stood in the way of American expansion. From among the tribes' leaders, several stood out to officers at Fort Larned by March, 1867, including Satanta and Kicking Bird of the Kiowa; Tall Bull, White Horse, Bull Bear, Roman Nose, and Black Kettle of the Cheyenne; and Little Raven of the Arapaho. In March 1867, Captain Henry Asbury of the 3rd Infantry reported on his view of the situation from Fort Larned, noting, "The 'Cheyennes' talk but little but are among the most dangerous of the Indians on the Plains, on account of their superior qualities as soldiers." General Winfield Scott Hancock, a Union hero of the Battle of Gettysburg, arrived in western Kansas in 1867. Hancock was inexperienced dealing with American Indians, though was confident in his ability to bring them under control. Hancock met with several Cheyenne chiefs at Fort Larned on April 12. Legally unable to forge treaties with the tribes, Hancock instead sought to intimidate them into alignment with U.S. interests. "You know very well, if you go to war with the white man you will lose….I have a great many chiefs with me that have commanded more men than you ever saw, and they have fought more great battles than you have fought fights," Hancock warned the chiefs.

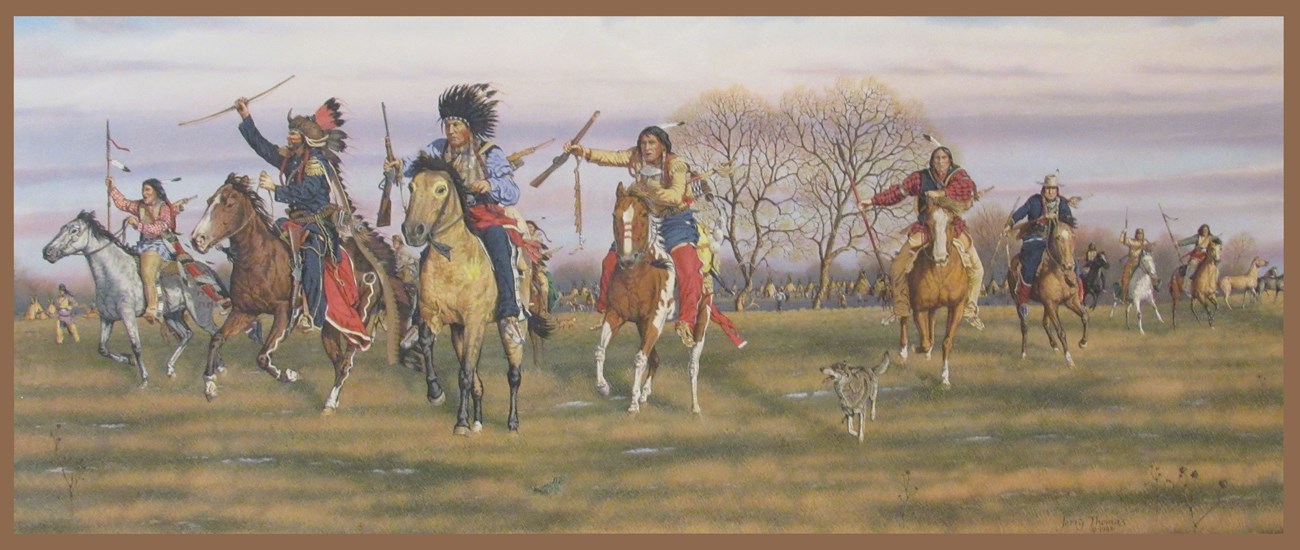

NPS Photo of the original painting which hangs in the Fort's Visitor Center. The sight of a massive formation of troops so near their village evoked memories of the Sand Creek Massacre, prompting the women and children to flee on the evening of the 14th, leaving most of their lodges and belongings behind. Hancock, who had brashly moved his troops to within sight of the village, evidently could not conceive of why the people would flee. Furious at what he took to be an offense, Hancock demanded their return. Some of the Cheyenne warriors obliged Hancock and rode to look for the women and children, but returned empty-handed. Fearing the repercussions of Hancock's anger, the remaining warriors also fled, eluding Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry as night fell.

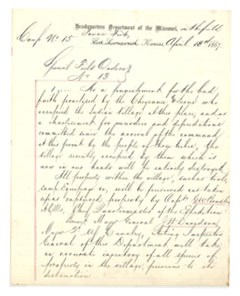

NPS Photo Hancock’s troops, particularly the 7th Cavalry, attempted to locate the villagers for several days but were unsuccessful. Assuming their flight indicated a disinterest in peaceful negotiation, Hancock concluded that the Indians meant war. Hancock ordered the abandoned village burned to the ground. "I am satisfied that the Indian village was a nest of conspirators," Hancock reported. It was the opening round in what became known as "Hancock’s War," an unprecedented season of violence on the plains of Kansas.

Word of the village's destruction quickly spread among the tribes. Battles raged across Kansas: Fort Dodge, June 12; Fort Wallace, June 21-22; Baca’s Wagon Train, June 22; Pond Creek Station and another at Black Butte Creek, June 26; Kidder’s Fight (in which Kidder's entire detachment was killed), July 2; Saline River, August 1-2; Prairie Dog Creek, August 21-22; Davis’s Fight, September 15. Raiding along the Santa Fe Trail also increased. With the cost of war increasing, the U.S. Government looked for alternatives. By the end of the summer, Hancock had been transferred to another command and was replaced by General Philip Sheridan. Fort Larned, where diplomacy had begun to unravel that spring, played a significant role in ending the season of warfare in October 1867 by supporting the negotiations for the Medicine Lodge Treaty. Artifacts from the Cheyenne village destroyed by Hancock's troops are on display in the Fort Larned visitor center. The village site is privately owned by the Fort Larned Old Guard and is closed to the public.

Public Domain |

Last updated: February 3, 2020