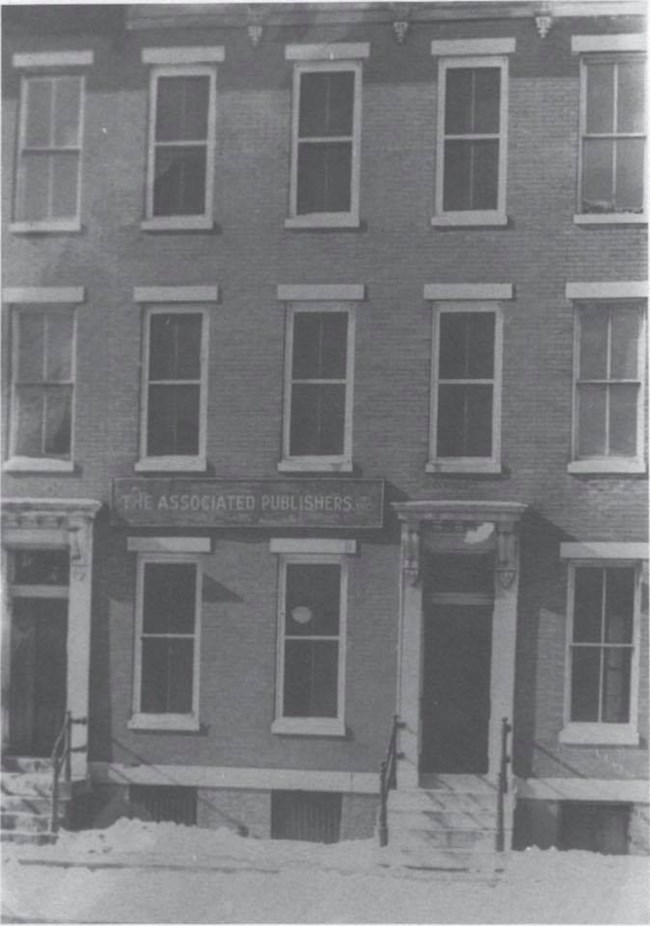

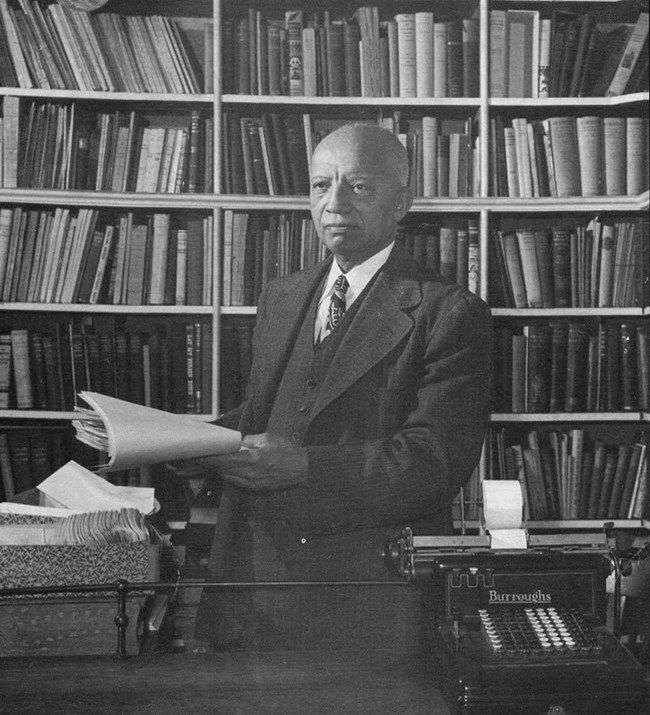

ASALH Institutionalizing the Study of Black HistoryDr. Carter G. Woodson purchased 1538 Ninth Street in Northwest, Washington, D.C. on July 18, 1922 for $8,000.00. His "office-home," as it was so-often called, would go on to play a vital role in his mission to promote the scholarly study, institutionalization, and popularization of Black History. His home housed the Associated Publishers, Inc. and served as the base of operation for The Journal of Negro History, The Negro History Bulletin, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc. (ASNLH), and where he created "Negro History Week" in 1926. According to Dr. Pero Dagbovie, Woodson “wrote and dictated to his secretaries and stenographers numerous books, letters, memos, announcements, and essays in the comfort of his office-home.” Important figures of the early Black History Movement either worked or visited the Association’s headquarters, and during the organization’s annual meetings that were held in the nation’s capital, the “national office” was certainly a busy place. Up and coming historians and scholars such as Drs. Rayford W. Logan, Charles H. Wesley, Lorenzo Johnson Greene, Luther Porter Jackson, Lawrence Dunbar Reddick, and John Hope Franklin were either employed by Woodson or sought his counsel and mentorship. The home was said to have functioned as an important mentoring center and “a training school for future historians who learned much from [a] master craftsman.” During the 1920s, the renowned poet and future leader of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes worked for Woodson. Hughes later recalled of his time with Woodson: “My job was to open the office in the mornings, keep it clean, wrap and mail books, assist in answering the mail, read proofs, bank the furnace at night when Dr. Woodson was away, and do anything else that came to hand which the secretaries could not do.” While the second floor of his home housed his office and library, the basement served as a make-shift archives. He preserved rare artifacts and collections that documented the African American and African Diaspora experience. In his annual report for 1941, he noted: “The Association…has on hand in its fireproof safe in the national office an additional 1,000 or more manuscripts which will be turned over to the Library of Congress as soon as they can be properly assorted. These manuscripts consist of valuable letters of the most noted Negroes of our time: Francis J. Grimke, Charles Young, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Richard Theodore Greerer.” Through Woodson’s work, the office-home became something of a gathering place for the community and an informal museum. Due to his collection of historical documents and artifacts, the office-home was an established place for research among scholars and members of Woodson’s associations.

Scurlock Studio Records A Lasting LegacyOn April 3, 1950 Woodson died in his bedroom, located on the third floor of the home. Upon his death, ASNLH president Mary McLeod Bethune said: “I loved Carter Woodson. He helped me to maintain faith in myself. He gave me renewed confidence in the capacity of my race.” Both the ASNLH and Associated Publishers occupied the home until 1971. In 1976, the nation recognized Woodson's achievements when his home was designated a National Historic Landmark and in 2003 when Congress named his home a National Historic Site. In 2006, the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site became the 389th unit of the national park system. Woodson’s office-home has clearly served many purposes and continues to serve and inspire future generations. A Locus of Black IdentityDr. Carter G. Woodson’s office-home was a central point of Black identity and culture in the larger Shaw neighborhood, also known as “Black Broadway”. In addition to Woodson, other prominent activists, entrepreneurs, educators, artists, and musicians lived and worked in the neighborhood including Mary McLeod Bethune, Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, and Mary Church Terrell. This community of influential African Americans in the early decades of the 1900s helped to strengthen and define a specific Black identity and space within the segregated society of Washington, D.C. and more broadly, the United States. [From] the boisterous 1920s to the riots of the 1960s, the area north of downtown Washington known today as ‘Shaw’ was the pre-eminent African American neighborhood in the city.… The neighborhood was distinguished by influential residents, important churches, literary and professional societies, and excellent public and private schools. Black businesses and entertainment establishments drew African Americans from all over Washington. - Michael Andrew Fitzpatrick, in Willing to Sacrifice: Carter G. Woodson, the Father of Black History, and the Carter G. Woodson Home by Dr. Pero Dagbovie Timeline of the Carter G. Woodson Home NHS

|

Last updated: December 23, 2024