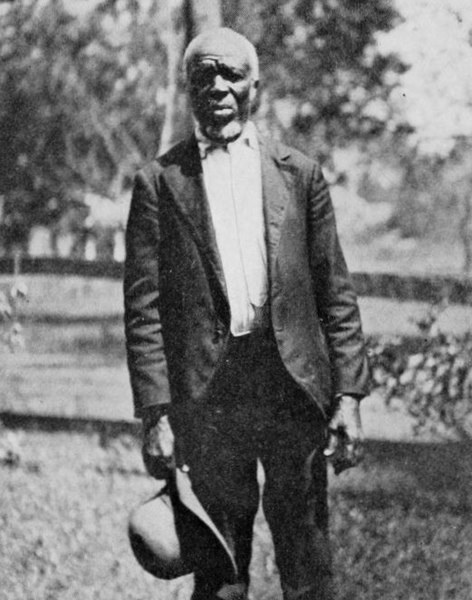

Library of Congress Uncovering HistoryZora Neale Hurston was an author and anthropologist, known for her works such as Their Eyes Were Watching God and Mules and Men. In 2018, another impactful work from Hurston, Barracoon, was published. This book told the story of Cudjo Lewis, who was born as Oluale Kossola. Kossola was thought to be the last of the 110 survivors of the Clotilda, which was one of the last slave ships to travel from the United States to Africa. Even though the transatlantic slave trade was abolished in the United States in 1807, thousands of Africans were still brought illegally to the United States to be enslaved until the 1860s.1 While Kossola’s story is not representative of the millions of African people enslaved in the United States, it is still important to know his experience and Hurston’s journey to obtain it.Hurston began working as an investigator for Dr. Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) in 1927. Hurston was recommended by her professor, Franz Boas, for a $1,400 fellowship that Woodson and the American Folklore Society’s Elsie Clews Parson were offering. She was to travel for six months throughout Florida and other places in the South to collect folklore from the Black people living there. One task from Woodson was to examine historical records relating to Fort Mose, a Black settlement in St. Augustine, Florida established in the seventeenth century. Also during this expedition, Hurston first interviewed Kossola in Mobile, Alabama. Based on this interview, the article, “Cudjo’s Own Story of the Last African Slaver,” was published in The Journal of Negro History along with the Fort Mose material. Unfortunately, there is evidence that this article was largely plagiarized from another book, Historic Sketches of the Old South by Emma Roche. However, Hurston did get a chance to redeem herself by conducting a series of interviews with Kossola in 1928 that would constitute the basis of Barracoon.2

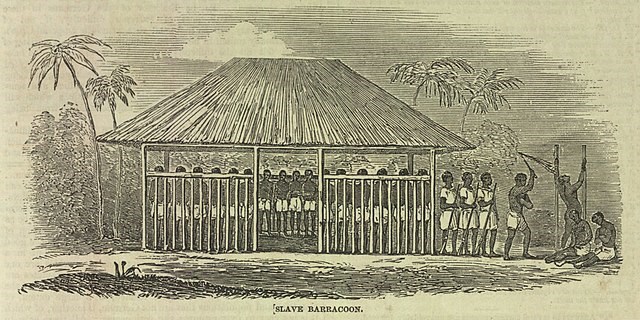

Historic Sketches of the South (New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1914) Experiences That Will Never Be ForgottenIn Barracoon, Hurston names two reasons for writing the book. As discussed above, Hurston was assigned to interview Kossola as a part of her fellowship with the ASNLH. Most importantly though, was her desire to convey the story of those who were captured from Africa and enslaved because their stories were not usually told. To emphasize this point, Hurston wrote, “all these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold…the thoughts of the ‘black ivory,’ the ‘coin of Africa,’ had no market value. Africa’s ambassadors to the New World have come and worked and died, and left their spoor, but no recorded thought.”3 As such, Hurston recorded Kossola’s story “in his own way without the intrusion of interpretation,” which she acknowledges may not be scientific in nature but was nonetheless true.4 While Hurston did have many critiques about Woodson, they were both dedicated to documenting Black history and culture, even if they would have disagreed on how this could be best achieved.5 Hurston made steps to correct the wrongs of the historical record regarding enslaved people by centering Kossola’s perspective in Barracoon.Kossola offers Hurston a comprehensive recollection of his life. He begins his story with his grandfather who worked as an officer to the king, which was an important starting point for him. Kossola then discusses his parents, family, and childhood games. He also explains the cultural practices of his people, such as their marriage and funeral rites, justice system and initiations into manhood. He then details the raid by Dahomey on his town, Bantè, that led to his capture and the journey to the barracoon in Ouidah, where he was imprisoned until he was sold to William Foster, the captain of the Clotilda and one of the co-conspirators to the capture of Kossola and 109 others. They arrived illegally in the U.S. in 1860, where they were enslaved until the end of the Civil War in 1865. After gaining their freedom, he and others from the Clotilda bought the land to establish Africatown. Kossola would get married and have six children. Sadly, Kossola faced further hardships as he was unable to work after being hit by a train and denied justice under the legal system. Kossola survived his wife and children, and his yearning for his family and homeland is apparent in his narrative. Overall, by telling his story Kossola ensured that his experiences and others alike would never be forgotten.6

Illustrated London News, 1849 Preserved and Made Available for This and Future GenerationsHurston made many attempts to publish Barracoon but was unsuccessful until 2018. The original manuscript was not initially published partly because Hurston was dedicated to authentically representing Kossola’s story by writing in his dialect.7 Even still, Hurston’s work was not lost. She discussed her experience interviewing Kossola in her autobiography, Dust Track on a Road. Others, such as Sylviane A. Diouf, also contributed to scholarship surrounding the Clotilda. Dreams of Africa in Alabama examines the lives of the Clotilda survivors before, during, and after their capture. After Barracoon’s publication in 2018, more scholarship emerged surrounding the survivors of the Clotilda. Hannah Durkin published two articles in 2019 and 2020 about two other survivors of the Clotilda, Sally “Redoshi” Smith and Matilda McCrear, both of whom lived longer than Kossola. Hurston actually met one of the women, which is evident in a letter sent to Langston Hughes in which she says, “’Found another one of the original Africans, older than Cudjo about 200 miles up state on the Tombig[b]ee river. She is most delightful, but no one will ever know about her but us.’”8 While Hurston may not have gotten the recognition she deserved for this book while she was alive, its importance to understanding the experiences of the survivors of the Clotilda cannot be understated. Through Barracoon and her other works, Hurston places herself amongst the great preservationists of her day.written by Sydney Coleman [1] Zora Neale Hurston, Barracoon: the Story of the Last "Black Cargo", ed. Deborah G. Plant (New York, NY: Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2019). [2] Valerie Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows: a Biography of Zora Neale Hurston (London: Virago, 2004), 142-167. [3] Hurston, Barracoon [4] Ibid. [5] Zora Neale Hurston, Zora Neale Hurston: a Life in Letters, ed. Carla Kaplan (New York: Anchor /Doubleday, 2003). [6] Hurston, Barracoon [7] Ibid. [8] Hannah Durkin (2019) Finding last middle passage survivor Sally ‘Redoshi’ Smith on the page and screen, Slavery & Abolition, 40:4, 631, DOI: 10.1080/0144039X.2019.1596397 |

Last updated: December 23, 2024