Lamar University Archives and Special Collections A Region Rich in TimberIt is no wonder that the lush forest landscape that is the Big Thicket would eventually command the attention of the lumber industry. The Piney Woods of east Texas have always been home to pines and hardwoods, though the dense growth and wet terrain made access to the region difficult. Prior to the 1880s, inhabitants of the region were scarce and sparse, creating only small inroads to small settlements and cabins living off subsistence farming while hunting small game. The richness of the region’s resources did not go without notice, but the realities of the region’s climate and the dense thicket made it overall unexploitable. However, as technology progressed and forest resources on the East Coast and around the Great Lakes began to dry up, lumber companies turned their attention to the South. The Early YearsThe extraction of lumber from the Big Thicket started in the early 1800s and was one of the first major industries to take root in the area. There were few roads and even fewer easily accessible ones. The dense shrubbery of the region and frequent flooding made construction of such infrastructure difficult and tedious. Instead, rivers like the Neches were used to float resources out of the thicket and towards the mills along the coast. Texas saw its first major sawmills established in cities like Houston, Galveston, Beaumont and Orange while smaller sawmills existed inland to serve local needs.

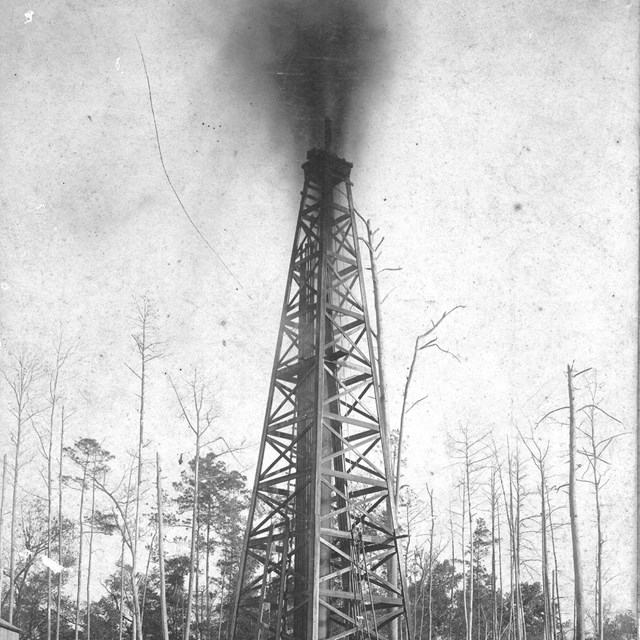

Lamar University Archives and Special Collections Railroads and the Bonanza EraThe lumber industry in the thicket changed drastically with the expansion of the railroad and saw its boom in what is known as the “Bonanza Era” lasting from roughly 1880 to 1930. Prior to the Civil War there were railroads through the region, though the lines weren’t extensive. During the war these lines were torn for scrap. After the war, amidst reconstruction efforts, the railroads were reinvested in. The state of Texas was liberal in their land grants, granting land to railroad companies for each mile of track. Many of these investments came from the lumber industry that saw an opportunity in an expanded railroad system. In Beaumont, for example, the Long and Company Sawmill sold a right-of-way to the newly reorganized Texas and New Orleans rail line for $1 in 1876. From 1880 to 1883, Herman and Augustus Kountze, two bankers from New York who had acquired thousands of East Texas timberland and for whom the town of Kountze gets its name, rebuilt the old Eastern Texas Railroad from Sabine Pass to Beaumont and eventually expanded north into the woods. Up-and-coming lumberman John Kirby built a small railroad from Beaumont to Kirbyville in 1896 that would eventually stretch all the way to Louisiana. By 1880, the railroads connected most of east Texas to major depots throughout the state, opening new frontiers to the lumber industries.

Lamar University Archives and Special Collections Fall and RiseDespite the success of this era, or perhaps because of it, it could not last forever. By 1920, the lumber companies saw many of the supply exhausted. Coupled with the effects of the Great Depression, most companies either left the thicket for the forests of the Pacific Coast or went bankrupt. 1932 saw the lowest lumber production since 1880. Ecological Effects of LoggingPrior to the Bonanza Era, the forests of the Piney Woods were tall and wide. The pine forests encompassed an area roughly the size of Indiana. Early surveyors noted pine that was 150 feet tall and five feet in diameter. Today, the average pine diameter in the Big Thicket is about four inches to one foot. Bald cypresses were measured to have up to 17 feet in girth. The thicket was an old forest within the Piney Woods filled with tall trees, dense understory and teeming with life. It was also one of the last havens for forests that had already disappeared elsewhere. The longleaf pine forest, for instance, was an ecosystem that once stretched from east Texas to Virginia. In colonial times, this pine turned out to be very valuable and the old-growth habitat slowly disappeared. The old-growth longleaf pine of the Big Thicket remained shielded for a time given the climate of the region, but this changed in the Bonanza Era when railroads made the pine more accessible. A Silver LiningThe mill towns of the Bonanza Era were short-lived. Once the forests that could be reached from the railroad lines were completely chopped, the tracks were torn up, the mill was dismantled, and the companies and laborers were moved on to the next patches of land. By the early 1900s, much of the thicket’s pine forests had been reduced to cut-over woodlands. Lumber companies used a “cut-out and get-out” method of logging, leaving a “forest of stumps” in their wake. However, at no point was technology or transportation anywhere near efficient enough to allow the deforestation of the entire thicket at once. The climate of the region allows for quick regrowth. While much of the thicket was harvested, the slowness of the process meant that much of the ecosystem remained intact and the forest slowly regrew. While the old growth that many early visitors fawned over was lost, the general ecosystem of the region, and thus its biodiversity, remained.

Lamar University Archives and Special Collections ClearcuttingThis silver lining changed with the introduction of clearcutting. Unlike the cut-out and get-out method where only the marketable trees were cut, clearcutting first cut and shipped out the marketable trees, then bulldozed the others as well as all the understory plants into large heaps and then burned the heaps. Once the land is completely cleared, the lumber company can plant new pine saplings. This method even goes as far as filling in creeks and streams. In southeast Texas, the pine planted was usually loblolly pine, chosen for its quick growth. The newly planted plots can then be harvested in 15-25 year cycles. This type of lumbering practice began in this region in the 1930s, alongside the “second-growth” efforts of the time but took off in the 1960s and persists to this day. Logging TodayToday, the lumber industry still thrives. As you drive on the roads and highways around the Big Thicket, logging trucks can be easily spotted turning their way out of the forests and transporting their loads to the numerous industries in the towns surrounded by the Thicket that make use of the lumber, whether it be the paper mill in Evadale or the Hardwoods of Woodville.

NPS Photo ConservationUnlike in the past, however, logging now exists directly adjacent to conservation. As the forests of the Thicket began to disappear, it ushered forth such groups as the Big Thicket Association who desired to see the Piney Woods protected from further shrinking. The region is now sprinkled with Big Thicket National Preserve, state parks and conservation sanctuaries. While the industry continues around the protected lands, and in some cases, even within it, the conservation efforts having arisen since the 1960s have ensured that, at least in part, the ecosystems of the region can persist. Combined, these lands strategically protect stream and river corridors protecting water quality and allowing for animal and plant circulation throughout the ecosystem without compromising the economy of the lumber industry.

Abernethy, Francis E. n.d. “Big Thicket.” Handbook of Texas Online. Accessed June 3, 2020. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/gkb03. |

Last updated: February 23, 2025