(Singing) Rosario Dawson: Cast off the shackles of yesterday! Shoulder to shoulder into the fray!

Oh come on...you know this

Retta & RD together: Our daughters' daughters will adore us And they'll sing in grateful chorus "Well done, Sister Suffragette!"

[Riff on memory of Mary Poppins / song]

RD: ala...I mean literally this was all I knew about suffrage at some point. From Mary Poppins. Jane and Michael Banks’ mom marching into the living room on Cherry Tree lane emblazoned with her sash. It was exciting, but what the heck were they singing about!? I’ll admit I never really went much further than this lyric. Like I just fast forwarded to supercalifragilisticexpialidocious. But I googled the lyrics, ok. And later Mrs. Banks sings:

"Womankind, arise!" Political equality and equal rights with men! Take heart! For Missus Pankhurst has been clapped in irons again!”

RD: So this is interesting, because while this song was brought to us by the all-American Walt Disney company, this was not an American suffrage anthem. It was about our sisters in arms across the pond -- the British suffragettes.

Fun fact - suffragette is a word that comes out of England, and you don’t use it to describe women’s voting rights activists stateside. It’s actually kind of derogatory here.

Oh and that Missus Pankhurst? She was the founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union. That group that became the driving force in British suffrage for nearly two decades. It would also influence militant, socialist suffrage activism around the world. Well before you or I sang along to Mary Poppins.

R: Well I just learned a lot! Thanks Rosario.

[Theme]

RD: And I’m Rosario Dawson.

R I’m Retta. And this is And Nothing Less.

Episode Five: Sister Suffragette - The Fight for the Vote Around the World

[THEME]

RD: So, if you remember, in 2011, after the Egyptian revolution, people credited social media as both the spark and the accelerant for social change. Facebook and Twitter made it easy for everyday revolutionaries to organize with speed and inspire with ease.

It would be easy, then, to assume, that social movements like suffrage in the 19th and early 20th century, would be small and insular. It was a time, after all, without Twitter or Instagram. Women’s rights activists back then didn’t have the benefit of digital technology. It must have been very provincial.

In reality, though, the US women’s suffrage movement was international from the start.

RD: When the women convene at Seneca Falls, their demands for women’s rights are not written in a bubble. You can see direct links to calls for human rights made by revolutionaries in Europe, the French West Indies, Mexico and of course, by Native tribes in America.

So how did all this information get around?

R: Ellen DuBois is a research professor at UCLA and the author of Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote. She concedes that early in suffrage history - in the middle of the 1800s - travel and the sharing of information wasn’t as easy as it is now. But ideas still flowed.

Dubois: There were relatively quick ships. And so it was via newspapers and letters that people got their information and so within three or four weeks they might know of something. So from our point of view, if we start in 1848, the women who led the Seneca Falls convention were quite well informed about the international environment. And the international environment on the one side meant that they knew a lot about what we call the revolutions of 1848. These are democratic revolutions. That is to say, popular revolutions seeking to create the basis of a democratic franchise. France, Italy, Germany and other places.

R: Reading international news gave many Americans the ability to compare and contrast political styles and states.

RD: If we stick with 1848, as an example, we know that for the most part, women and men of color did not have the right to vote across the U.S.

But, it was still ahead of most countries in the world in terms of democratic voting rights. This is because most countries restricted voting based on property ownership. In the US, however, virtually all white men could vote regardless of whether or not they owned property.

Dubois’ assessment?

DuBois: This was really the cutting edge of democracy.

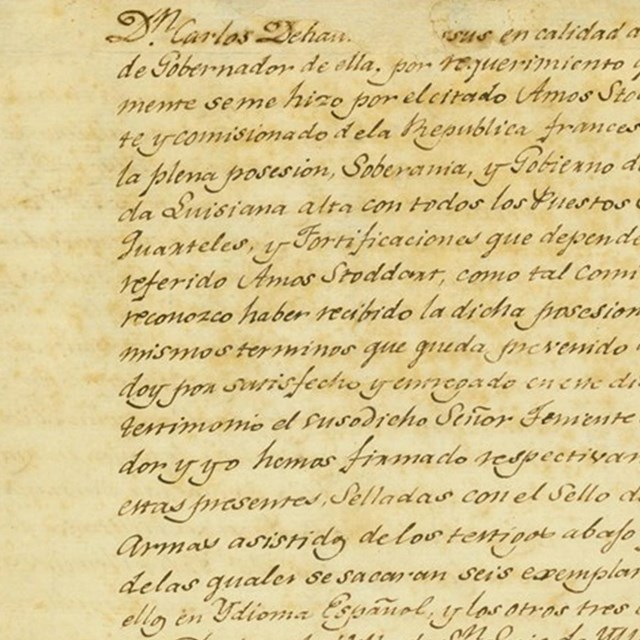

By contrast, she looks south, to Latin America.

DuBois: About the time of the Seneca Falls convention, all of northern Mexico becomes part of the United States. It's a very crucial development for what's going on in Seneca Falls, because that land accession, which increases the landmass of the United States 40 percent, something like that, throws a grenade into American politics. electoral party politics, because the compromises that had been established to keep the issue of slavery out of national politics. Dependent on only apply to the prior territories of the United States, especially those of the Louisiana Purchase. And that meant that all of this land, which would go from California to Texas to Colorado, was opened territory for political battles. And this sets the stage very quickly for a dramatic revolution in American party politics, which means that national politics and the right to vote become crucial to the issue that's so important to these women, which is the history. The future of whether slavery will exist.

[music]

R: This grenade, as Ellen DuBois calls it, gets thrown into American politics a mere six years after the Seneca Fall convention. So that’s 1854. The issue of slavery breaks open the country. And suffragists were determined to take political action.

RD: This desire to be political created deep international connections that would continue to grow. And the technology enabled it.

The first transatlantic telegraph lines were constructed in the 1860s, during American reconstruction and the birth of transnational communications, travel and print culture.

The 1880s and early 1900s saw the birth of world organizations in temperance, peace and suffrage. You had the World’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union founded by Frances Willard, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom founded by Jane Addams and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance founded by Carrie Chapman Catt, all in partnership with allies around the world.

R: Women were traveling and communicating internationally to share ideas about civil rights, human trafficking, equal pay for equal work, arbitration, marriage rights and of course, voting.

The World’s Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which was the international arm of the American group we’ve heard about, would become the largest of the international women’s organizations with over forty national affiliates.

DuBois: That was the first organization concerned with the condition of women that really had global outreach.

And its outreach was primarily to the east. It was influential in Japan. And elsewhere in the east.

R: The connection between the WCTU and suffrage can’t be overstated according to historians. And its leader, Frances Willard,

DuBois: she takes this connection between suffrage and temperance to the next level. I should say that the connection between temperance and woman suffrage was a direct one. The essence of it was that. Drinking, alcoholism was primarily a condition of men as far as women were concerned, it meant violence in a domestic violence and economic deprivation within the family.

Frances Willard is able to convince her organization this is not radical women who have forged their political skills in the radical anti-slavery movement. This is an organization made up of very conventional Protestant small-town women. And she is able to convince this organization to go on record in support of women's rights to vote. It's the first really national organization which takes suffrage from a small radical movement to really the beginning of a mass movement of women.

R: For example, The WCTU is credited with the world’s first national suffrage victory in New Zealand in 1893. They led a campaign of petitions, lectures, debates, editorials, and even sometimes, cricket matches.

Temperance club members were also active in education, fair pay, and women’s health.

RD: But, although groups like these spoke of global sisterhood, their membership was usually segregated, with white branches and “colored” branches.

The politics were also rather conservative.

But all this would change.

[Music]

That’s right, we’re talking [whispers] feminists in just a minute. On And Nothing Less.

//

BREAK / SHORTIE

//

R: So here we are in a new century. And the suffs are welcoming more modern and international politics.

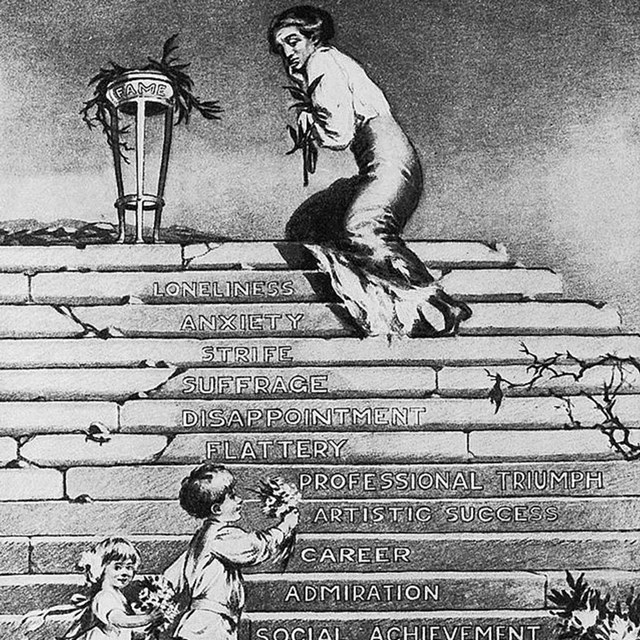

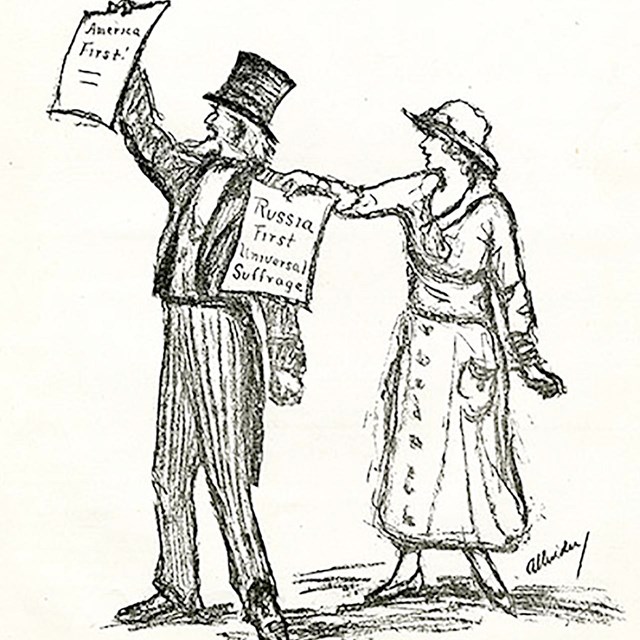

RD: You’re starting to see the word feminist. And political women are reading about the 1917 Russian Revolution, fair labor and socialism. A wave of social democratic and labor parties in Europe would contribute to women’s movements. And Americans took note.

R: Alice Paul, who would become one of the most famous suffrage protesters, was very attentive to international movements. She was first inspired to join the suffrage cause while in graduate school in England.

In 1907 she caught a lecture by a daughter of our “Sister Suffragette,” Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst. A week later, at a suffrage march in Hyde Park in London, she heard calls for “Votes for Women!” echoed by bugles and saw colorful banners and flags. She was hooked.

RD: It was not all rah-rah for women, however. Suffragettes were regularly hit with stones and abused. Paul and others were repeatedly arrested and mistreated. To protest this, they went on hunger strikes. And eventually were brutally force fed by prison guards.

The stories of these horrors would reach Americans. Here again, historian and author Ellen DuBois.

DuBois: In the early 20th century, the British suffrage movement takes off like a rocket. It starts out in the northern part of the country, in the mill towns and the manufacturing towns of the north of England. The popular basis of it is are women workers. They draw on some of the energies of the labor movement in England, which is quite radical.

And they conduct these what they call monster parades in 1908 and 1909 in 1910. And they are unlike anything that's ever been seen and they absolutely are covered in the international press.

There are Americans, lots of them who go to England and learn what's going on. Carrie Chapman Catt, Anna Howard Shaw, even African-American women, a woman named Sarah Garnet. She's the second wife of a man named Henry Highland Garnet, who's one of the great figures of the abolitionist movement. And she goes to England and brings back information about this exciting set of new developments.

One of these radical suffragettes, the first one who comes to United States, comes at the invitation of this African-American woman, Sarah Garnet, and speaks to her group.

It's not possible to overstate the influence of this development on the American movement. It generates a militant, to use the word of the period, a militant wing of the suffrage movement which cannot find a place for itself in the suffrage mainstream. And it is this movement that conducts the militant tactics that. It's a lot of what we know about in the final years of suffrage.

RD: Alice Paul returns to the United States in 1910 after her final imprisonment in London. She needed to recover...Paul was force fed daily, sometimes fifty times, while in jail. And she was also driven to further the suffrage effort at home, armed with tools she learned overseas.

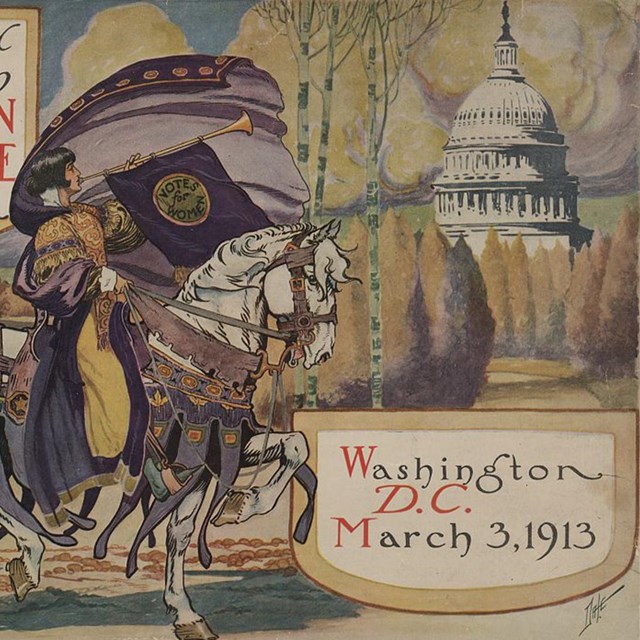

She and others conduct these massive parades. She's responsible for the 1913 Washington, D.C. parade, which is an imitation of the British parade. And then in 1917, when the United States goes to war. They're not supporting the American entry into the war.

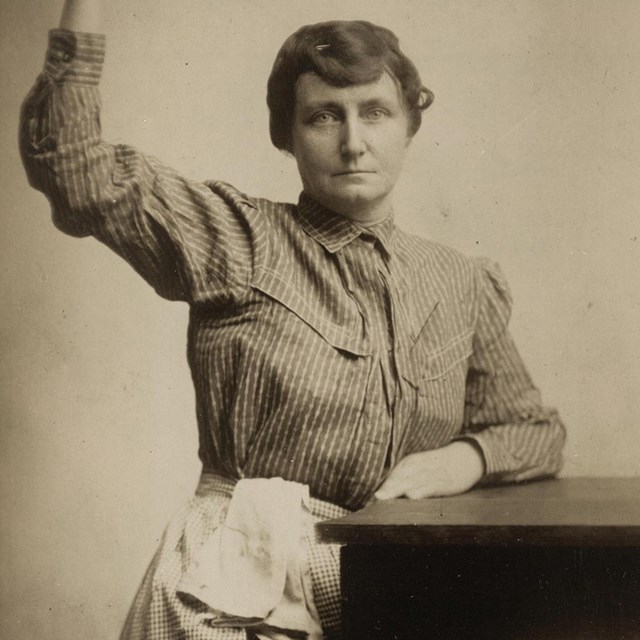

R: Maybe you’ve seen photos of women standing in front of the White House Gates..? R: Well, those 1917 Silent Sentinels -- as they were called -- are part of one of the most famous events in suffrage history. They did it first ...they literally invented protesting in front of the White House.

R: One of their signs read, “Mr. President how long must women wait for Liberty?”

President Wilson was initially uninterested. But, still these picketers, organized by the National Woman’s Party, came back six days a week, no matter the weather for almost a year.

Once the U.S. entered World War I, this kind of hostility in front of the White House lawn was seen as unpatriotic. But the NWP didn’t stop. And for many months, they were arrested and faced violence. More than 150 women went to jail. And more women went on hunger strikes, including, their leader, Alice Paul. And again they were force-fed.

But with news of this, on top of reports of women being beaten, choked and kicked in prison, public opinion was on the side of the suffragists.

And just a few months after the Silent Sentinels protest, President Wilson and Congress would send the US into World War I. What would this mean for women and the vote?

RD: Well, just look at what was happening around the world. In the years leading up to our entry into the war, European and other North American countries had already been in the fight. And many of those women also got the right to vote -- Denmark, Russia, Canada, Austria, Germany, Poland, and England - all passing voting laws between the years 1915 and 1918.

Weiss: Yes, unfortunately, it's true that the war did advance the cause of suffrage.

RD: That’s journalist Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour.

Weiss: So what happens when America--It's looking like we are going to be drawn into the war in 1916. Woodrow Wilson campaigned for reelection on the. The slogan “he kept us out of war.” So he reluctantly enters the war. And the suffragists see this happening, And so the Americans have been watching their French and German and all the European countries that are drawn into the what's called the Great War, we call World War I now, and especially the British suffragists who are very much a sister movement to America, very much moving in parallel.

And there are even the radical suffragists give up the suffrage fight to commit themselves to war, work to helping their nation get through the war when three years later, when America is being drawn in.

Carrie Catt sees this coming and says makes a decision, a really painful decision for her. She is a pacifist. She at first opposes any entry of America into this bloody war. She and Jane Addams of Hull House of Chicago found something called the Women's Peace Party to advocate that America stay out of the war, stay neutral. But what she realizes when things are getting hot and it's going to be harder and harder for America not to enter the war. She sees that the cause of suffrage will be advanced if American suffragists pledge their help to the nation.

RD: Even though Catt is a pacifist, she eventually has to make a painful moral compromise. If she wants to further the cause of suffrage, she knows she has to publicly pledge that she and her two million supporters will get behind the war and get behind the country.

Weiss: If she publicly pledges that American women will not give up their quest for suffrage, but will put it behind the importance of war work or at least put it equally, that they'll move equally together, that this will strengthen the hand of the suffrage cause in Congress. Remember, that federal amendment has been sitting there for 40 years and they can't get it out. And so she makes this very, very painful decision to pledge the loyalty and the work of the two million women of the National American Association [NAWSA] to the suffrage cause.

And this is a big, big decision. President Wilson trumpets that this is important to him. Alice Paul, says, no, we are not going to support this. And so she--her National Women's Party never supports World War I. And pickets during--those pictures of them picketing the White House. Their imprisonment, their torture all takes place while America is fighting in World War I. And they're called, those National Women's Party picketers are called not only unpatriotic by the press and by much of the American public, but also traitors, because this is done in wartime.

RD: Whether or not to support the war tears the movement apart. But once the President and Congress made a decision to commit, the role of women in the country radically changed.

American women were working in munitions production, overseeing liberty loan fundraisers and food conservation efforts. The decision of some suffragists to focus on the needs of the nation proved to only further their cause.

Weiss: The arguments used by male politicians for so long that women don't deserve the vote because they're not strong enough, they're not smart enough, they're not mentally capable of making these hard decisions. When women have been serving in the war effort in ways they'd never served before, they're in the mines. They're in the factories, they've taken over the fields and the women's land army.

They are running the streetcars, they're doing things that were considered men's work and were vital for them to take over. So it gets really hard for a male politician to spout out these ideas that, you know, women are just too fragile and nervous and hysterical to be able to vote. And this was Carrie Catt’s calculation. And she was very right.

[music]

R: And so you saw a real change in public attitudes toward women. You also saw changes in attitude toward the President, who said that the world must be safe for democracy. He had to respond to people who asked, how safe is democracy at home, when half the citizens can’t participate?

Weiss: So it's no coincidence that everything starts moving, that the amendment passes. Congress goes to the states right after we exit World War I.

R: Just a month before the war ended, and almost exactly one year after the first picketers took their posts outside the gates of the White House, the President finally gave his support to women voting.

“We have made partners of the women in this war,” he said. “Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege?”

He knew this would be heard at home and around the world.

DuBois: The women's rights movement and the women's suffrage movement and feminism have always been global movements.

DuBois: In the United States we talk about waves of feminism. I've tried to pursue that metaphor. And waves aren't discrete things. They are movements of energy through bodies of water. So if we think of the waves of an ocean, we can imagine that after lapping up on the shores of the United States, those those waves of motion continue elsewhere. So in my experience, the feminist movement moves about the world. But it never dies.

But at times, for instance, in our country where feminism has seemed to have been quiet, at the same time, those energies have moved to other countries in other nations and they will come back to us.

RD: “So even though 2020 is a year to look at an American suffrage anniversary, don’t think of the history of women’s right to vote as a national story, says DuBois. Think of it as a global story.”

[Music]

R: Next time, World War One is over, but the suffrage fight is not.

Weiss: Tennessee could be the pivotal last state or it could be the beginning of the end of the momentum and the suffragists might have to wait who knows how long.

I’m Retta

RD: And I’m Rosario Dawson

Thanks for listening

[CREDITS] RETTA

This was And Nothing Less, from the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission, PRX, and the National Park Service. This podcast was envisioned by W-S-C-C Executive Director Anna Laymon with support from Kelsey Millay.

The production team is Executive Producer Genevieve Sponsler, Producer & Audio Engineer Samantha Gattsek, and Writer & Producer Robin Linn. Our music is by Erica Huang.

The historical content used to create these stories was brought to you by the National Park Service -- teachers can download companion lesson plans at go.nps.gov/suffragepodcast.

For even more suffrage history, visit the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission at womensvote100.org.

Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst Sarah Garnet

Sarah Garnet Dr. Alice Paul

Dr. Alice Paul Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw

Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw Jane Addams

Jane Addams Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt National Historical ParkWomen's Rights National Historical Park

National Historical ParkWomen's Rights National Historical Park Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights

Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights National MonumentBelmont-Paul Women's Equality

National MonumentBelmont-Paul Women's Equality Occoquan Workhouse

Occoquan Workhouse Frances Willard House

Frances Willard House President's Park (White House)

President's Park (White House) Suffrage in 60 SecondsTemperance

Suffrage in 60 SecondsTemperance Suffrage in 60 SecondsWoman Suffrage Procession

Suffrage in 60 SecondsWoman Suffrage Procession Suffrage in 60 SecondsPicketing the White House

Suffrage in 60 SecondsPicketing the White House Suffrage in 60 SecondsTraitors or Patriots?

Suffrage in 60 SecondsTraitors or Patriots? Suffrage in 60 SecondsJail Door Pin

Suffrage in 60 SecondsJail Door Pin Suffrage in 60 SecondsThe Night of Terror

Suffrage in 60 SecondsThe Night of Terror Did You Know? Suffragist vs. Suffragette

Did You Know? Suffragist vs. Suffragette International Connections to US Suffrage

International Connections to US Suffrage The Necessity of Other Social Movements

The Necessity of Other Social Movements African American Women and the 19th

African American Women and the 19th Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase Democracy Limited: The Prison Special

Democracy Limited: The Prison Special Women in World War I

Women in World War I Silent Sentinels

Silent Sentinels 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession

1913 Woman Suffrage Procession