Last updated: February 20, 2025

Person

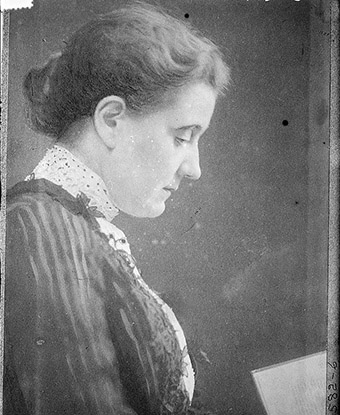

Jane Addams

Bain News Service, Collections of the Library of Congress.

When Jane Addams penned Twenty Years at Hull House: With Autobiographical Notes, she presented her life story as inextricably tied to her work in running a settlement house. Addams was born into an affluent family in Illinois, but comfort and leisure did not suit her. After spending much of her early life searching for outlets for progressive work, Addams became a reformer. In 1889, this led her to found Hull House in Chicago, IL with a group of like-minded reformers.[1] From within the walls of a spacious, abandoned mansion, Addams and her colleagues created a sanctuary for immigrants who wanted to both settle and thrive in the city. Addams saw this work as a major part of her life story; another examination shows that this was but one important chapter.

Prior to creating Hull House, Addams completed her education at Rockford Female Seminary. The president of her class, Addams was a bright and ambitious woman born to a well-connected family. Her father, Illinois senator John Addams, left a sizeable inheritance that enabled her to pursue her education even further. After Rockford, Addams enrolled at the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia, PA, but personal health issues derailed her career in medicine. Searching for her purpose, Addams set out to find a different kind of education; she soon embarked on an extensive, long tour of Europe.

During her trip abroad, Addams became a critical observer of society. Deeply moved by the suffering of others, and especially the indigent, Addams sought solutions to the problems faced by residents of densely packed cities. Addams returned from this trip energized to create a settlement house similar to what she’d seen in Toynbee Hall, a social settlement in London. From her base at Hull House, which she co-founded with her partner, Ellen Gates Starr, Addams became a highly influential progressive in Chicago.[2] In addition to providing direct social services for those who came through the settlement, Addams fought for better labor conditions, safe play spaces, cleaner city streets, a court system for juvenile offenders, and much more.

From the 1890s on, Addams became more involved with both progressive social issues and party politics. When Theodore Roosevelt ran for president in 1912, Addams offered her endorsement, seconding his nomination in Chicago during a convention of the Progressive Party. Addams had gained significant power and influence by this point through her advocacy work, yet she still could not vote. Addams continually campaigned for suffrage, both nationally and internationally, bemoaning that “It is always very difficult for me to make a speech on woman suffrage. I always feel that it belongs to the last century rather than this.”[3] In 1913, the state of Illinois granted suffrage to women; the 19th Amendment was passed a few years later.

Addams was widely regarded as an important voice and conscience in this period known as the Progressive Era. Public opinion sharply changed when she fought against the entry of the United States in World War I. Throughout her life, an important tenant of Addams’s politics was pacifism. Addams was involved in the meeting of the International Congress of Women in 1915 at The Hague and she became a leader in the Women’s Peace Party and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Addams’s resistance to the war and accounting of worldwide suffering were seen by many, including agents within the Federal Bureau of Investigation, as unpatriotic.[4]

In 1931, just a few years before her death in May 1935, Addams was honored with a Nobel Peace Prize (shared with Nicholas Murray Butler). This came after a decade in which Addams was widely condemned for her pacifism. Addams may have found herself in Hull House, but the world was changed because she also used her voice so far outside of it, too.

A project through the Save America's Treasures Grant Program, which helps preserve nationally significant historic properties and collections, funded work to preserve and cold store master negatives of the Jane Addams Hull House Photograph Collection in 1999.

[1] Hull House, 800 S. Halsted, Chicago, Illinois was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 23. 1965. The house and the dining room wing were documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

[2] Addams and Starr met in college. Addams later met, and set up house, with Mary Rozet Smith, who also worked with her at Hull House. They were together for over thirty years, reffering to each other as though they were married. Their relationship ended with Smith's death in 1934.

[3] Jane Addams, “Speech on Woman Suffrage,” June 17, 1911.

Learn more about Hull House here: http://npgallery.nps.gov/pdfhost/docs/NRHP/Text/66000315.pdf

https://www.nps.gov/thri/jane-addams.htm

http://npgallery.nps.gov/pdfhost/docs/NRHP/Text/66000315.pdf

http://npgallery.nps.gov/pdfhost/docs/NRHP/Text/66000315.pdf

Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House (1910)

Victoria Bissell Brown, The Education of Jane Addams (2007)

Lucy Knight, Citizen: Jane Addams and the Struggle for Democracy (2005)