Last updated: June 12, 2023

Article

Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights on the President’s Doorstep (Teaching with Historic Places)

"Aerial view of Lafayette Park and Washington Mall, Washington, D.C." Carol M. Highsmith, 2006, Library of Congress.

Every day the women with their banners marched across the park to take up positions in front of the White House. They came from the headquarters of the National Woman’s Party (NWP) on Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C. Their banners demanded that President Woodrow Wilson help them in their campaign to get all American women the same right to vote that American men already had. They maintained their vigil every day for two months, through the rain and snow of January and February 1917.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees all Americans freedom of speech and of assembly and the right to petition their government. What better place to exercise those rights than in front of the White House? When these brave women chose to take their protest to the president’s front door, they blazed a trail for thousands of Americans who have come to Lafayette Park to exercise their right as citizens—their right to be heard.

The NWP pickets began to encounter violent reactions from onlookers after the United States entered the First World War in April 1917. The police began to arrest them and to imprison them under harsh conditions. Many people were shocked when they learned about the women’s treatment. Some lawyers thought the sentences imposed were in violation of the First Amendment. The women continued to demand their rights, in spite of the violence they endured. The 19th Amendment, guaranteeing all women in America the right to vote, finally became part of the Constitution in 1920, three years after the first pickets marched to the White House.

By exercising their First Amendment rights, the women provided a model for many others. Groups and individuals have demonstrated against the Vietnam War, for rights for gays and lesbians, for and against abortion, and for civil rights. U. S. citizens and foreign nationals also protest on issues or events occurring around the world that they believe the United States should be aware of and become involved in. All of these people have presented their causes and their grievances to the president in Lafayette Park—where he could not ignore them.

About This Lesson

Lafayette Square, in Washington, D.C., is listed in the National Register of Historic Places by virtue of its designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1970. This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places documentation “Lafayette Square Historic District” (with photos) and on materials on Lafayette Park and the National Woman’s Party (NWP). The lesson was written by Marilyn Harper, former Teaching with Historic Places historian, and edited by staff members of the Teaching with Historic Places program, President’s Park, National Park Service, and the White House Historical Association.

The lesson was made possible by a generous grant from the White House Historical Association. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, government, and civics courses in units on early 20th century reform movements, American political history, or women’s history.

Time period: Early 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights on the President's Doorstep

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

- Standard 3B–The student understands the guarantees of the Bill of Rights and its continuing significance.

Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

- Standard 1B–The student understands Progressivism at the national level.

- Standard 1C–The student understands the limitations of Progressivism and the alternatives offered by various groups.

Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the Present)

- Standard 2E—The student understands how a democratic polity debates social issues and mediates between individual or group rights and the common good.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights on the President’s Doorstep

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

- Standard A - The student compares similarities and differences in the ways groups, societies, and cultures meet human needs and concerns.

- Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

- Standard D - The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.

- Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

- Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

- Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

- Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

- Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

- Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land uses, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

- Standard B - The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

- Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

- Standard G - The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

- Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

-

Standard B - The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

-

Standard C - The student describes the various forms institutions take and the interactions of people with institutions.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard A - The student examines persistent issues involving the rights, roles, and status of the individual in relation to the general welfare.

- Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

- Standard H - The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice, and influence to the examination of persistent issues and social problems.

-

Standard I - The student gives examples and explains how governments attempt to achieve their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard F - The student demonstrates understanding of concerns, standards, issues, and conflicts related to universal human rights.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard A - The student examines the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

-

Standard B - The student identifies and interprets sources and examples of the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

-

Standard C - The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard D - The student practices forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard G - The student analyzes the influence of diverse forms of public opinion on the development of public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard H - The student analyzes the effectiveness of selected public policies and citizen behaviors in realizing the stated ideals of a democratic republican form of government.

-

Standard J - The student examines strategies designed to strengthen the "common good," which consider a range of options for citizen action.

Objectives for students

1) To examine the relationship between Lafayette Park and the White House;

2) To explain the importance of the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment, using the NWP women’s suffrage campaign of 1917-1920 as a case study;

3) To describe the campaign and to explain why NWP leaders decided to make Lafayette Square the party’s headquarters;

4) To identify places in the local community where controversies about First Amendment rights have occurred.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can be used directly on the computer or printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a small version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps showing the White House, Lafayette Park, and Lafayette Square;

2) two readings about the NWP and its suffrage campaign;

3) one document, the text of a speech by President Wilson;

4) six photos of the suffrage campaign;

5) one political cartoon relating to women’s suffrage.

Visiting the site

Lafayette Park is a seven-acre landscaped area and is part of President’s Park, which is composed of the park lands surrounding the White House and its grounds. Both the White House and President’s Park are part of the National Park System. The buildings that face Lafayette Park form a neighborhood known as Lafayette Square. Some of the buildings on the Square are open to the public, but most are not. The park and its surrounding streets are public spaces. A visit to the site should begin at the White House Visitor Center, located at 1450 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, open daily from 7:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. The Visitor Center contains exhibits and background information, as well as other visitor services. The White House can be viewed from Lafayette Park and the surrounding streets, but visitors need to contact their congressional representatives to arrange for tours. For more information, visit the President’s Park website.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

"Woman Suffrage Banner," Harris and Ewing, 1917, Library of Congress

What do you think is going on in this photo?

Setting the Stage

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The new U.S. Constitution was sent to the states for approval in 1787. Many state legislatures strongly criticized it because it did not include specific protections for the individual liberties that Americans had fought for during the Revolution. The Constitution was ratified in June 1788 without a bill of rights, but the first Congress elected under the new system took up the question of adding one as soon as it convened in March 1789. Eventually, 12 separate amendments were submitted to the states. They quickly ratified all but two of them. These first ten amendments, which became known as the Bill of Rights, entered into force on December 15, 1791.

The Bill of Rights protects the liberties at the heart of the American system of government. Many scholars think the First Amendment may be the most important of them all. The First Amendment is often at the center of the nation’s bitterest conflicts.

Suffrage, the right to vote, is not one of the rights protected by the Bill of Rights. The Constitution left decisions about who could or could not vote to the states. At the time the Constitution was adopted, most states allowed only property owners and taxpayers to vote. The vast majority of voters were white men, but white women who met the property qualification could vote in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and New Jersey. By the early 1800s, all four states had enacted universal white manhood suffrage, but excluded women.

The first call for voting rights for women came in 1848, at the First Women’s Rights Convention, held in Seneca Falls, New York. By the 20th century, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the oldest and largest of the women’s suffrage organizations, was concentrating on amending state constitutions to allow women to vote. By 1916, women could vote in 12 western states, but the campaign seemed to have stalled. In 1917, a small group of determined, impatient women set out to extend the vote to all women by amending the U.S. Constitution. The proposed amendment had been introduced in Congress in 1878, reintroduced every year for almost forty years, but never brought to a vote. The women’s attempts to gain the rights of full, participating members of “We the People” would test the ability of the First Amendment to protect the liberties it guaranteed. They picked Lafayette Park, across from the White House in full view of the president, as the stage for their campaign.

Locating the Site

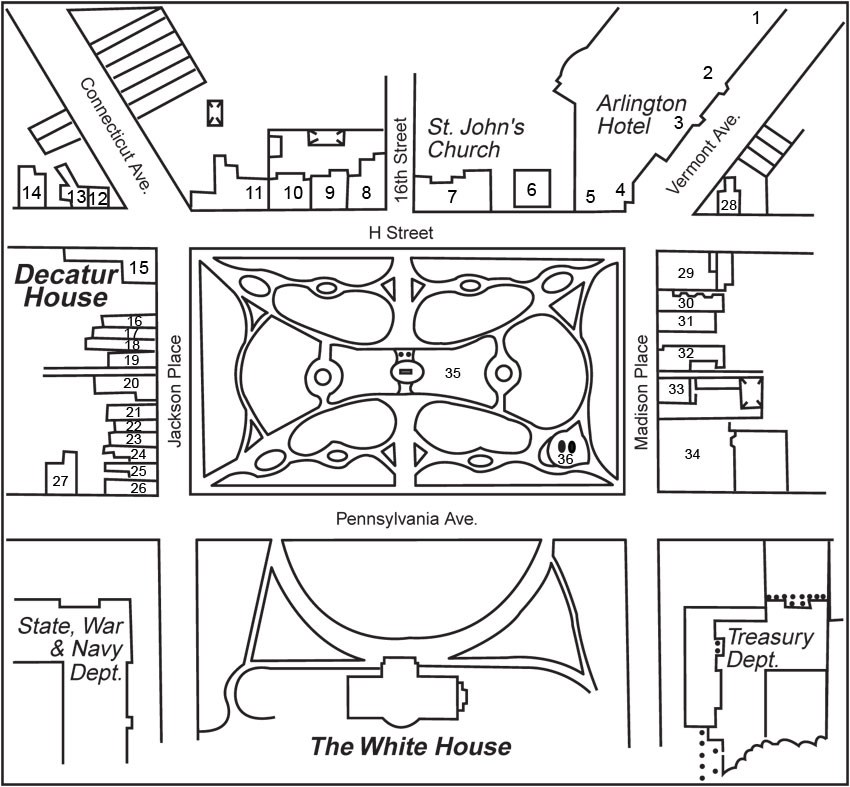

Map 1: The White House, Lafayette Park, and Lafayette Square

National Park Service

Questions for Map 1

1) Find the White House on this map. What is its relationship to Lafayette Park and to Lafayette Square, the neighborhood surrounding the park? Washingtonians have gathered in Lafayette Park to celebrate joyous events and to mourn great tragedies for more than 200 years. Why do you think the park has been so important to people who live in the city?

2) The White House is a powerful symbol for all Americans. Why do you think that is the case? What do you think it represents?

3) In the original plan for Washington, the grounds of the “President’s House” were much larger than they are today. They extended from H Street on the north to what is now Constitution Avenue on the south and from 17th Street on the west to 15th Street on the east. Outline this area on the map. Why might the planners of the new capital city of Washington have thought the President’s House needed so much land?

4) When Thomas Jefferson was president, he decided that the grounds of the White House were too big. He built a fence around the immediate White House grounds, opening up the north side of President's Park, later renamed Lafayette Park, to the public. Why do you think he might have done that?

5) What kinds of buildings surround Lafayette Park today? How would you describe the neighborhood?

Map 2: Lafayette Park and Its Surroundings in 1891

National Park Service

This map is based on a map included in an article published in Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly in April 1891. The article included a key as a caption for the map:

Numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 constitute what is now the Arlington Hotel. The following names indicate former or present residents:

- Reverdy Johnson, Senator and Minister to England; James Buchanan and Benjamin Harrison, Presidents-elect; the Prince of Wales.

- William L. Marcy, Secretary of War and Secretary of State.

- Lewis Cass, Secretary of War and Secretary of State.

- Senator Charles Sumner.

- Senator Pomeroy.

- Lord Ashburton, British Ambassador.

- St. John’s Episcopal Church, attended by all the Presidents prior to Lincoln.

- John Hay, poet and historian.

- Henry Adams, author and grandson of President John Quincy Adams.

- Senator John Slidell; Walter A. Wood, inventor and manufacturer (present occupant).

- Senator Daniel Webster; Mr. Montothlon, French Ambassador; William Corcoran, banker (last occupant).

- Admiral Shubrick (last occupant).

- Judge Bancroft Davis, Secretary of State and Minister to Germany (present occupant).

- George Bancroft (last occupant).

- Commodore Stephen Decatur; Henry Clay; Martin Van Buren, Vice-president; Edward Livingston, Secretary of State; George M. Dallas, Vice-president; General Beale (present occupant).

- William L. Marcy, Secretary of War; Representative Newberry, of Michigan; Senator James G. Blaine; Representative William L. Scott (present occupant).

- Charles C. Glover, banker (present occupant).

- William Murtagh, Editor; General Frank Steele (present occupant).

- Major-General J. G. Parke.

- Commodore Stockton; Levi Woodbury, Secretary of the Treasury under Van Buren; John C. Spencer, Secretary of the Treasury under Tyler; General Daniel E. Sickles; Vice-president Schuyler Colfax; Washington McLean, Editor Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Mrs. James Blair, daughter of General Jesup.

- Senator Gorman; George F. Appleby (present occupant).

- Admiral Alden; Major Henry R. Rathbone; General N. L. Anderson; Senator Dolph (present occupant).

- Mrs. Green, daughter of Admiral Dahlgren; Colonel William H. Philip.

- John McLean, Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Peter Parker, Minister to China; Bureau of American Republics, William E. Curtis, chief.

- Francis P. Blair; Montgomery Blair; Thomas Ewing, Secretary of the Treasury.

- Rev. Smith Pyne; Commodore Morris.

- Dolley Madison; Commodore Wilkes, General McClellan; Cosmos Club (present occupant).

- William Windom, Secretary of the Treasury.

- Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll.

- Ogle Tayloe; Admiral Paulding; Senator Don Cameron (present occupant).

- Henry Clay, Secretary of State; John C. Calhoun, Vice-president; Washington Club; William H. Seward, Secretary of State; James G. Blaine, Secretary of State.

- United States Attorney-general’s office.

- Jackson’s equestrian statue.

- Lafayette’s monument.

Questions for Map 2

1) Study the map carefully before looking at the key. What clues can you find that might help you figure out how the buildings in the Lafayette Square neighborhood were used in 1891?

2) Now look at the key to the map. It lists some of the people who lived in these buildings during the 19th century. What kinds of jobs did these people have? Why do you think they might have chosen to live on Lafayette Square?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The National Woman’s Party and Lafayette Park

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

--First Amendment to the U. S. Constitution

In 1917, Alice Paul and her National Woman's Party (NWP) set out to use their First Amendment rights to gain the vote for all American women. They chose Lafayette Park as the stage for their protest because of its location. It was right across the street from the White House, the home of Woodrow Wilson, the president of the United States. The women thought they had to gain his support to succeed.

Paul was a young, well educated American woman from a prosperous Quaker family in New Jersey. She had recently returned from England, where she had worked with the most radical wing of the British women's suffrage movement ("suffrage" means the right to vote). She went through violent confrontations with the police, jail sentences, hunger strikes, and force feedings while she was there. When she came back to the United States, she tried to bring some of the militancy of the British suffragettes to the American suffrage campaign.1

In 1912, Paul became chairman of the Congressional Committee, part of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The committee soon moved its headquarters from New York to Washington, D.C. The nation’s capital was a better place to lobby for the passage of a constitutional amendment granting all women in America the right to vote.

On March 3, 1913, the day before President Wilson's inauguration, the committee organized a massive suffrage parade. This was only two months after it moved to Washington. Bands, floats, and over 5,000 people, mostly women, marched down Pennsylvania Avenue. An unruly crowd of onlookers attacked the marchers. The police made no effort to control the violence. The parade brought the committee's cause national attention.

Parades were among the new tactics Alice Paul and her organization used in the suffrage campaign. The women also added pageants, street speaking, demonstrations, and mass meetings. They learned these techniques from many sources, including the British suffrage campaign, and the temperance and anti-slavery movements. They focused on federal office-holders in Washington. They quickly learned to turn the violence they encountered into a political advantage.

The NWP was established as an independent political party in 1916, with Alice Paul as its head. In that same year, the new party set up its headquarters in Cameron House on Lafayette Square. Cameron House was one of a number of private houses on the square converted to offices. The square was changing rapidly in 1916. Large office buildings had replaced some of the original houses. Fewer wealthy and ambitious men thought they had to live close to the White House. Diplomats, bankers, and philanthropists now lobbied lawmakers in lavish new houses located away from downtown. Lafayette Square was, however, a very strategic and prestigious address for organizations like the NWP.2

Streetcar lines ran along Pennsylvania Avenue and H Street, which were among the busiest streets in the city. Lafayette Park was still a garden, with shade trees, flowerbeds, and curving gravel paths. Four large statues of Revolutionary War heroes now stood at the corners of the park. In 1902, the Army Corps of Engineers reported that “Lafayette Park was the most highly improved and the most centrally situated small park in the city . . . seen and used by more people than any other.”3

In 1916, the leaders of the new NWP had decided they needed to be more aggressive in pressuring the government. Their expanded tactics included direct confrontation and civil disobedience. The campaign targeted President Wilson, their neighbor across Lafayette Park. At first, the president was polite to suffrage delegations, but he would not change his public position. He insisted that the states had the responsibility for deciding whether women could vote or not. Privately he told a friend "suffrage for women will make absolutely no change in politics–it is the home that will be disastrously affected.”4

Questions for Reading 1

1) Why do you think Alice Paul chose Lafayette Square as the headquarters of her new political party? What advantages do you think that location might have had for her campaign for women suffrage (refer to Maps 1 and 2, if necessary)?

2) How did the tactics of the suffrage campaign change in 1916?

3) What do you think President Wilson meant when he wrote that “the home . . . will be disastrously affected” if women got the vote? How do you think the women would have reacted if they had known his private opinion?

Reading 1 is adapted from materials prepared by Janice Ruth and Barbara Bair, historical specialists, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, for the Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party on-line exhibit on the Library of Congress American Memory website; and George Olszewski, Lafayette Park (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1964).

1British women working for voting rights are usually called "suffragettes." In the United States, men and women supporting women’s suffrage referred to themselves as "suffragists.”

2In 1919, the National Woman's Party moved to the Ewell House at 14 Jackson Place, across the park. They stayed there for 20 years.

3James M. Goode, Washington Sculpture: A Cultural History of Outdoor Sculpture in the Nation's Capital (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 464-472; Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers (Washington, DC: Office of Public Buildings and Grounds, 1902), 2541, cited in Lafayette Square (Reservation 10), Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS No. DC-676, 8.

4Nancy Saunders Toy, Diary, quoted in Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Vol. 32; January I-April 16, 1915, Arthur S. Link, ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, Press, 1980), 21.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Picketing and Protest: Testing the First Amendment

On January 10, 1917, a dozen determined women left National Woman's Party (NWP) headquarters and marched across Lafayette Park to the White House. They carried purple, white, and gold flags and banners. The banners read, "Mr. President, What Will You Do for Woman Suffrage?" and "How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?" Every day for the next few cold and wintry months, women took up their stations in front of the White House as "silent sentinels."

The dictionary defines picketing as a "practice, used in labor and political disputes, of patrolling, usually with placards, to publicize a dispute or to secure support for a cause.”5 American labor unions began using this tactic in the 19th century. The unions claimed that the First Amendment protected picketing, but state courts usually ruled against them. British suffragettes and the Women's Political Union in New York City had already used picketing effectively in their suffrage campaigns. NWP lawyers told the women that what they wanted to do was not against the law.

At first, onlookers greeted the pickets with curiosity and sometimes support. President Wilson smiled and tipped his hat as he left the White House grounds. By March, he refused even to look at the women. Public reactions to the pickets changed dramatically in April 1917, when the United States entered World War I. In the frenzy of patriotism that followed, many women stopped campaigning for the vote and devoted themselves to war work. The NWP did not announce its support for the war and did not suspend its picketing. By the summer of 1917, the party's attacks on Wilson were becoming harsher and more personal. Newspapers began calling the women "hecklers" and "women howlers.”6

Many people thought it was unpatriotic for the NWP to criticize the government during wartime. Some even thought it was dangerous and subversive. Mobs started threatening the pickets and destroying their banners, while the police did nothing.7 In June 1917, police began arresting suffrage pickets for blocking traffic. In July and August, there were more arrests. The women served their jail sentences under harsh conditions in old, unsanitary buildings. They were sometimes beaten. Alice Paul and other leaders of the NWP went on hunger strikes and were brutally force-fed.

The women’s treatment was front-page news even during wartime. The publicity shocked the nation and brought attention, sympathy, and support for the suffrage cause. With women doing so much for the war effort, government officials were already having trouble denying them the vote. Anti-suffrage arguments about women's mental and physical inferiority were less convincing as women took the jobs left behind by men drafted into military service. Finally, on January 9, 1918, President Wilson announced his support for the suffrage amendment. The next day, it passed the U.S. House of Representatives.

The NWP immediately began a campaign to force the U.S. Senate to pass the amendment. Members set up picket lines in front of the Capitol and the Senate Office Building. Bystanders and police attacked them and there were more arrests. In August 1918, the women began to hold mass meetings in Lafayette Park. In March, a federal appeals court had decided that the earlier arrests and detentions were unconstitutional, but the police still arrested more than 60 women and sent them to prison.8 Many of them went on hunger strikes. In mid-September 1918, the pickets began burning copies of Wilson's speeches at the mass meetings. On September 30, Wilson made a speech to the Senate, asking the senators to pass the suffrage amendment to help win the war. The amendment was defeated again. The count was two votes short. (Two-thirds of the Senate must approve a Constitutional amendment.)

The end of World War I on November 11, 1918, had no effect on the NWP's efforts to force Wilson to get two more senators to vote for the amendment. On January 1, 1919, the women began a series of "watch-fire" demonstrations. Flaming urns were set up in front of the White House and in Lafayette Park. Women dropped copies of any Wilson speeches and books that mentioned "liberty," "freedom," or "democracy" into the fires. The pickets kept the fires burning even when bystanders and policemen put the flames out. More women were arrested, this time on charges of lighting fires on public property. They immediately began hunger strikes. In February, the women burned a picture of the president and more arrests followed. The suffrage amendment was still one vote short in the Senate.

The Senate finally passed the federal suffrage amendment on June 4, 1919. This began a fierce 14-month campaign for ratification by three-quarters of the states. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the amendment. The 19th Amendment, stating simply that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex,” became part of the U.S. Constitution eight days later.

The brave members of the NWP defended their First Amendment rights and their right to dissent even in wartime. At great personal cost, they picketed and protested to secure voting rights for women in every state of the Union. Women of all classes risked their health, jobs, and reputations to join the protests. According to one historian, approximately 2,000 women picketed between 1917 and 1919 and 500 women were arrested. Of these, 168 went to jail, some more than once. The NWP made heroes of the suffrage prisoners. The women went on nationwide publicity tours dressed in their prison garb. Everywhere they went, they spoke about their experiences in prison, winning much public support for their cause.9

The members of the NWP did not work alone. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) also supported the federal suffrage amendment, although its leaders feared that the NWP's "unladylike" behavior and the "unwelcome" publicity would make it difficult to gain widespread support for women's voting rights. They supported the government during World War I and opposed the NWP’s picketing as unpatriotic. In spite of these differences, the NWP militants helped NAWSA by making the older organization appear moderate by comparison. Politicians who were beginning to reconsider their anti-suffrage position could respond to NAWSA’s support of a suffrage amendment without appearing to yield to the “extreme” tactics of the NWP. Both organizations could rightly claim success when women all over the United States voted for the first time on November 2, 1920.

By exercising their First Amendment rights, the women of the NWP provided a model for many others who have used Lafayette Park as a stage to present their protests to the president on his own doorstep.

Questions for Reading 2

1) What happened in Lafayette Park on January 10, 1917? Why do you think the NWP decided to use picketing as part of its campaign to gain votes for women? What advantages might it have? What disadvantages?

2) Go back to Reading 1 and read the text of the First Amendment carefully. Explain each of its clauses in your own words. Do you think it protects picketing? Why or why not? In July 1917, a NWP lawyer defending the pickets asserted in court that the sentences imposed on them violated their constitutional right to “petition for redress.” Why do you think he used this section of the amendment as the basis for his argument? Do you think it is the most appropriate one to use? Explain your answers.

3) What effect did U.S. entry into World War I have on the women’s voting rights campaign? Why did many people become less tolerant of criticism of the government? Do you think criticism that is acceptable in peacetime should be unacceptable when the country is at war? Why or why not?

4) Many NWP members were educated women from comfortable homes. How do you think the treatment they endured in prison would have affected them? Many of them came back to the picket lines to be arrested over and over. Why do you think they did that? What issues might make you want to do what the women did?

5) Many people read in the newspapers about how the women were treated. How do you think they would react to these stories? Do you think men and women would have reacted differently? If so, why? Do you think the arrests of the pickets helped or hurt the cause of suffrage?

Reading 2 was adapted from materials prepared by Janice Ruth and Barbara Bair, historical specialists, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, for the Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party on-line exhibit on the Library of Congress American Memory website.

5“Picketing,” Dictionary of Business Terms, Barron's Educational Series, Inc, 2000.

6 Entry for June 30, 1914, "Detailed Chronology: National Woman's Party History, "Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party,” on-line exhibit, Library of Congress American Memory website.

7 Christine Lunardini, From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928 (New York: New York University Press, 1986), 128.

8 Robert P. J. Cooney, Jr., Winning the Vote: The Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement (Santa Cruz, CA: American Graphic Press, in collaboration with the National Woman's History Project, 2005), 363; entry for March 4, 1919, "Detailed Chronology: National Woman's Party History," Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party on-line exhibit, Library of Congress American Memory website.

9 Linda G. Ford, Iron Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, MD; University Press of America, 1991), 3.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: President Wilson’s Address to the Senate, Sept. 30, 1918

GENTLEMEN OF THE SENATE: The unusual circumstances of a world war in which we stand and are judged in the view not only of our own people and our own consciences but also in the view of all nations and peoples will, I hope, justify in your thought, as it does in mine, the message I have come to bring you. I regard the concurrence of the Senate in the constitutional amendment proposing the extension of the suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged. I have come to urge upon you the considerations which have led me to that conclusion. It is not only my privilege, it is also my duty to apprise you of every circumstance and element involved in this momentous struggle which seems to me to affect its very processes and its outcome. It is my duty to win the war and to ask you to remove every obstacle that stands in the way of winning it.

I had assumed that the Senate would concur in the amendment because no disputable principle is involved but only a question of the method by which the suffrage is to be extended to women. There is and can be no party issue involved in it. Both of our great national parties are pledged, explicitly pledged, to equality of suffrage for the women of the country. Neither party, therefore, it seems to me, can justify hesitation as to the method of obtaining it, can rightfully hesitate to substitute federal initiative for state initiative, if the early adoption of the measure is necessary to the successful prosecution of the war and if the method of state action proposed in the party platforms of 1916 is impracticable within any reasonable length of time, if practicable at all. And its adoption is, in my judgment, clearly necessary to the successful prosecution of the war and the successful realization of the objects for which the war is being fought.

That judgment I take the liberty of urging upon you with solemn earnestness for reasons which I shall state very frankly and which I shall hope will seem as conclusive to you as they seem to me. This is a peoples' war and the peoples' thinking constitutes its atmosphere and morale, not the predilections of the drawing room or the political considerations of the caucus. If we be indeed democrats and wish to lead the world to democracy, we can ask other peoples to accept in proof of our sincerity and our ability to lead them whither they wish to be led nothing less persuasive and convincing than our actions. Our professions will not suffice. Verification must be forthcoming when verification is asked for. And in this case verification is asked for,–asked for in this particular matter. You ask by whom? Not through diplomatic channels; not by Foreign Ministers. Not by the intimations of parliaments. It is asked for by the anxious, expectant, suffering peoples with whom we are dealing and who are willing to put their destinies in some measure in our hands, if they are sure that we wish the same things that they do. I do not speak by conjecture. It is not alone the voices of statesmen and of newspapers that reach me, and the voices of foolish and intemperate agitators do not reach me at all. Through many, many channels I have been made aware what the plain, struggling, workaday folk are thinking upon whom the chief terror and suffering of this tragic war falls. They are looking to the great, powerful, famous Democracy of the West to lead them to the new day for which they have so long waited; and they think, in their logical simplicity, that democracy means that women shall play their part in affairs alongside men and upon an equal footing with them. If we reject measures like this, in ignorance or defiance of what a new age has brought forth, of what they have seen but we have not, they will cease to believe in us; they will cease to follow or trust us. They have seen their own governments accept this interpretation of democracy,–seen old governments like that of Great Britain, which did not profess to be democratic, promise readily and as of course this justice to women, though they had before refused it, the strange revelations of this war having made many things new and plain, to governments as well as to peoples.

Are we alone to refuse to learn the lesson? Are we alone to ask and take the utmost that our women can give,–service and sacrifice of every kind,–and still say we do not see what title that gives them to stand by our sides in the guidance of the affairs of their nation and ours? We have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right? This war could not have been fought, either by the other nations engaged or by America, if it had not been for the services of the women,–services rendered in every sphere,–not merely in the fields of effort in which we have been accustomed to see them work, but wherever men have worked and upon the very skirts and edges of the battle itself. We shall not only be distrusted but shall deserve to be distrusted if we do not enfranchise them with the fullest possible enfranchisement, as it is now certain that the other great free nations will enfranchise them. We cannot isolate our thought or our action in such a matter from the thought of the rest of the world. We must either conform or deliberately reject what they propose and resign the leadership of liberal minds to others.

The women of America are too noble and too intelligent and too devoted to be slackers whether you give or withhold this thing that is mere justice; but I know the magic it will work in their thoughts and spirits if you give it them. I propose it as I would propose to admit soldiers to the suffrage, the men fighting in the field for our liberties and the liberties of the world, were they excluded. The tasks of the women lie at the very heart of the war, and I know how much stronger that heart will beat if you do this just thing and show our women that you trust them as much as you in fact and of necessity depend upon them.

Have I said that the passage of this amendment is a vitally necessary war measure, and do you need further proof? Do you stand in need of the trust of other peoples and of the trust of our own women? Is that trust an asset or is it not? I tell you plainly, as the commander-in-chief of our armies and of the gallant men in our fleets, as the present spokesman of this people in our dealings with the men and women throughout the world who are now our partners, as the responsible head of a great government which stands and is questioned day by day as to its purposes, its principles, its hopes, whether they be serviceable to men everywhere or only to itself, and who must himself answer these questionings or be shamed, as the guide and director of forces caught in the grip of war and by the same token in need of every material and spiritual resource this great nation possesses,–I tell you plainly that this measure which I urge upon you is vital to the winning of the war and to the energies alike of preparation and of battle.

That is my case. This is my appeal. Many may deny its validity, if they choose, but no one can brush aside or answer the arguments upon which it is based. The executive tasks of this war rest upon me. I ask that you lighten them and place in my hands instruments, spiritual instruments, which I do not now possess, which I sorely need, and which I have daily to apologize for not being able to employ.

Questions for Reading 3

1) How many times does President Wilson say that passing the suffrage amendment is necessary to winning the war? What reasons does he give to support that conclusion? Do you think his arguments are convincing?

2) Who were the people he says he listened to in making his decision? How does he describe the people he did not listen to? To whom do you think he was referring? Why do you think he included this passage in his speech?

3) What qualities does he seem to admire in women? Can you think of any other admirable qualities that he does not mention? Why do you think he chose the ones he did?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: National Woman’s Party Pickets,

February 1917

"Woman Suffrage Pickets at White House," Harris and Ewing, photographer, 1917, Library of Congress.

Questions for Photo 1

1) Identify the building in the background of this photo. Why do you think the National Woman’s Party (NWP) would have decided to locate their picket lines here?

2) Look carefully at this image. The attitudes of passers-by towards the women changed as the picketing continued. What do you think this photo tells you about public reactions at the time it was taken (refer back to Reading 2, if necessary)?

3) NWP organizers planned every detail of the picketing. They recruited volunteers for shifts of seven hours each. Suffragists traveled from 30 states to take turns on the picket line. The women in this photo were all from Pennsylvania. Why do you think the NWP would have made such careful arrangements? Why do you think these women made the trip to stand on the picket line?

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: “Russian” Banner, June 1917

"Woman Suffrage Banner," Harris and Ewing, photographer, 1917, Library of Congress.

Photo 3: Man Attacking “Russian” Banner, June 1917

"Woman Suffrage Banner," Harris and Ewing, photographer, 1917, Library of Congress.

Questions for Photos 2 and 3

1) Read the text of the banner carefully and summarize what it says in your own words. Look up the definition of democracy. Do you agree that America was not a democracy because it did not allow women to vote?

2) The women thought that preaching democracy abroad while denying half of the population the right to vote at home was hypocrisy. Do you think they were right? Explain your answers.

3) Bystanders tore the original banner down as soon as it appeared. Why do you think people were so angry about it?

4) National Woman’s Party members soon returned with identical banners. Why do you think they would picket with the same banner when they knew what had happened to the first one?

5) What appears to be happening in Photo 3? How do the women holding the banner seem to be reacting? Why do you think the photo is so fuzzy?

6) Do you think the First Amendment protects banners like this? Why or why not? Which section of the amendment do you think applies?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Pickets marching from National Woman’s Party headquarters to the White House on Bastille Day, July 14, 1917

Photograph 165-WW-(600A)2; American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs, 1917 - 1918; Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Record Group 165; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Questions for Photo 4

1) Read the text on the third woman’s banner. This was one of the most famous slogans of the French Revolution, which began with the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789. Why do you think the women selected that slogan for their banner?

2) Do you think the crowd of men surrounding the women was friendly or hostile? Why do you think so?

3) If you were one of the women, how would you have felt?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Alice Paul leads pickets out of National Woman’s Party headquarters, October 1917

"Woman Suffrage," Harris and Ewing, photographer, 1917, Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Questions for Photo 5

1) On October 19, 1917, the police announced that pickets arrested after that date could expect to be sentenced to jail for up to six months. This photo shows Alice Paul, the leader of the National Woman’s Party (NWP), leading a group of pickets to take up their positions at the White House on the next day. Look carefully at the expression on Paul’s face. What do you think that tells you about how she reacted to the police announcement?

2) Alice Paul was arrested and sentenced to seven months at the Occoquan Workhouse, the longest term ever handed down. While she was there, she demanded to be treated as a political prisoner. Look up the definition of “political prisoner.” Why do you think that is how she wanted to be recognized? Do you think she and the other pickets sent to jail fit the definition?

3) When Alice Paul’s demand for political prisoner status was denied, she began a hunger strike. The prison authorities force-fed her three times a day for three weeks. This involved pushing a tube down her throat and pouring liquid food directly into her stomach. What do you think this would have been like? Paul was transferred to the psychiatric ward at the District of Columbia jail later for “evaluation.” Why do you think the prison authorities might have done that?

4) Read the slogan on Alice Paul’s banner. Explain in your own words what you think it means. The slogan is quoted from one of President Wilson’s own speeches. The NWP often used such quotations on their banners. Why do you think they might have done that?

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Burning Wilson’s speeches in Lafayette Park, September 1918

"Lafayette, Marquis de. Suffragette Demonstration at Statue," Harris and Ewing, photographer, 1918, Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Questions for Photo 6

1) The women are standing in front of a statue. Whom does it commemorate? Locate the statue on Map 2. Why do you think the National Woman’s Party (NWP) might have picked this as an appropriate location for their protest?

2) Look carefully at the woman in the center of the image. Her name is Lucy Branham and she is holding a torch in her right hand. The charred piece of paper in her left hand is a speech by President Wilson. Lucy Branham called the burning a “symbolic act.” The women wanted action from the president, not just words. Do you think burning his speeches was an effective way to make their point?

3) Do you think the First Amendment protects symbolic acts? Why or why not? If so, which clause applies?

4) When the women began throwing copies of Wilson’s speeches into “watch-fire” urns in front of the White House and in Lafayette Park in October, soldiers and sailors rushed the women and overturned the urns. Why do you think people reacted so violently to the watch fires?

5) At one point, the women burned a picture of President Wilson. This action was highly controversial, even among other NWP members. Why do you think this might have been the case?

6) Do you think the First Amendment would protect the burning of speeches or pictures? Why or why not? If so, which section of the First Amendment would apply?

Visual Evidence

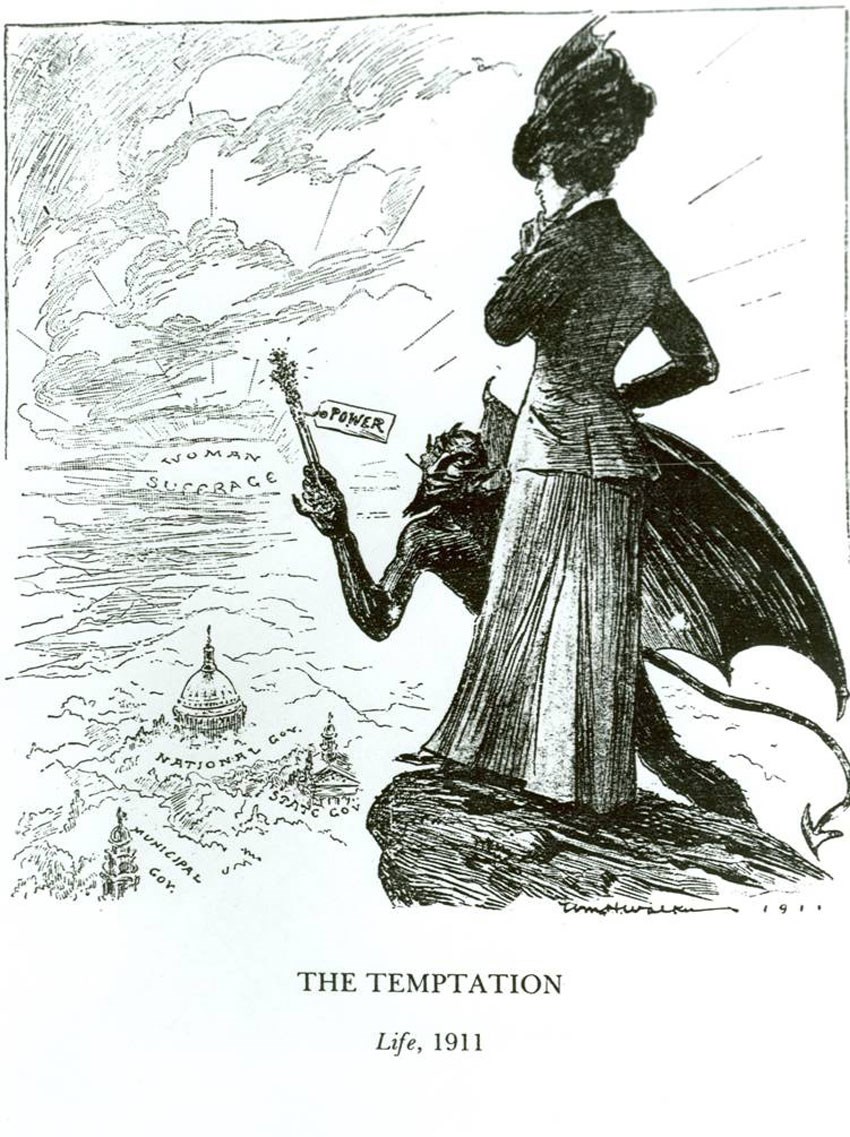

Illustration 1: “The Temptation”

Courtesy of The Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library, Staunton, VA

This cartoon appeared in Life magazine in 1911.

Questions for Illustration 1

1) Look carefully at this cartoon and describe in your own words what you see. It may be helpful to divide it into sections and list what you see in each one. What do you think it shows?

2) Who is being tempted? Who is doing the tempting? What is the temptation?

3) How does the woman appear to be reacting?

4) Cartoons often use symbols to carry their message. What symbols can you identify?

5) Do you think the artist supported or opposed women’s suffrage? Explain how you reached your conclusion.

6) Imagine replacing the image of the woman with one of a man. How do you think that would affect the message of the cartoon?

Putting It All Together

In this lesson, students have examined the protests that the National Woman’s Party (NWP) carried out in Lafayette Park in front of the White House between 1917 and 1920 to secure for all American women the right to vote. These protests asserted the women’s rights under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and paved the way for thousands of citizens and others to present their causes to the President on his own doorstep. The following activities will help students integrate and expand on what they have learned.

Activity 1: Following in the Women’s Footsteps

The NWP was one of the first organizations to use Lafayette Park as a stage for carrying their protests about government policies to the president, but not the last. This website discusses a number of protests that have taken place at the White House, in addition to the women’s suffrage campaign. Divide the students into small groups and ask each group to take one of the protests and find out more about it. Ask them to compare the one they have studied to the suffrage campaign and report back to the whole class. How was it the same? How did it differ?

Activity 2: Planning for Protest

The National Park Service, part of the U.S. Department of the Interior, has responsibility for taking care of Lafayette Park and for protecting the rights of all of the people who want to use it. This is not always an easy job. Many protests have taken place in the park since the women’s suffrage campaign of 1917 to 1920. In addition to those described on the “Citizen’s Soapbox” website, citizens and foreign nationals also demonstrate in Lafayette Park about issues or events occurring outside the United States. These demonstrations call attention to the situations, events, or issues happening around the world which the demonstrating individuals believe the United States should be aware of and become involved in solving or addressing. At other times, when foreign heads of state are visiting the White House, demonstrators on all sides of issues occurring in that nation ask for permission to demonstrate in Lafayette Park or on the White House sidewalk.

By the 1980s, some protesters were maintaining continuous vigils with elaborate semi-permanent signs and displays. Tourists complained that the large signs blocked their view of the White House. Ask the class to discuss how they would go about making decisions that would balance the rights of the protesters to free speech and the rights of citizens to enjoy a public park and see the home of their president. After the discussion, tell the students that what the Park Service eventually did was to limit each protester to two non-hand carried signs, to restrict the size of the signs to less than four feet by four feet, and to require the protester to remain with the sign(s) at all times. Ask the students whether they think that solution was a reasonable compromise.

Activity 3: First Amendment Rights

When the NWP staged its protests, there were many unanswered questions about what the First Amendment protected. Does freedom of speech protect only spoken words or does it also include actions? Should there be any limits on free speech in a democracy? Does the government have the right to set conditions on freedom of assembly in public spaces? Does the First Amendment protect people’s right to join any group they choose?

During the course of the 20th century, U.S. Supreme Court decisions gradually provided answers to these questions. The process was difficult, because people have very deep feelings about many of the issues involved and disagree strongly.

Divide the students into groups and ask each group to select one right mentioned in the First Amendment. Have them conduct research to identify important Supreme Court cases dealing with that right. They can find useful information in some of the websites and books listed in the Supplementary Resources section of this lesson. Ask each group to select one particular case and to write up the most important arguments used by both sides. Ask them to hold one or more mock trials, defending their positions in front of the whole class. Ask the class to reach a decision and then discuss why they agreed or disagreed with the Supreme Court’s decision.

Activity 4: Women and Violence

The protests of the British suffragettes eventually turned violent. That was one of the reasons many men and women, including the leaders of National American Woman Suffrage Association, opposed what they saw as the radical policies of the NWP. The right of peaceable assembly is one of the rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights and the NWP protesters never resorted to violence, but they often met with violence from onlookers. Ask the students to discuss the role that violence played in the NWP suffrage campaign. What do they think would have happened if the pickets, when arrested, had simply paid their fines and gone home? What might have been different if the prison authorities had treated the prisoners well?

Some students may want to study other non-violent campaigns for political change, such as Mohandas Gandhi’s campaign for Indian independence from Great Britain in the early 20th century or the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. How did they resemble the women’s suffrage campaign? How did they differ? Were the efforts of the authorities to suppress freedom of expression successful in any of these cases?

Activity 5: First Amendment Rights in the Local Community

Have students try to identify disputes that have occurred in the local community pertaining to rights identified in the First Amendment. Maybe the community was divided over separation of church and state, laws relating to equality and justice, medical choices, or other issues. One good way to find examples is to ask their parents or long-term residents. Disputes of this kind continue to be painful and divisive for many years and it may be difficult to get people to talk about them. These difficulties themselves may help students understand how important and how controversial First Amendment rights can be. They might also want to consider alternative ways of resolving disputes.

Are there places in the community associated with these disputes? Ask the students if they think these places should be recognized or preserved. Hold a discussion about whether it is important to commemorate painful community events or whether it is better to forget about them as soon as possible.

Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights on the President’s Doorstep

Supplementary Resources

By studying Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights on the President’s Doorstep, students will learn how one small group of determined women used Lafayette Park’s proximity to the White House to fight for their rights as citizens under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Their dramatic protests helped bring about the adoption of the 19th Amendment, which gave women all over America the right to vote. They also provided a model for many other demonstrators, who used the stage of Lafayette Park to present their causes to the president. Those interested in learning more will find much useful information on the internet.

President’s Park

Lafayette Park and the White House are both part of the National Park System. Visit the President’s Park website for operating hours, maps, schedules of events, and other information. The site also offers a walking tour that includes Lafayette Square.

Heritage Education Services, National Park Service

The Teaching with Historic Places website contains more than 135 curriculum-based lesson plans on places listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Decatur House: A Home of the Rich and Powerful discusses Stephen Decatur’s home on Lafayette Square as an example of the importance politically ambitious men and women placed on being in close proximity to the White House in the 19th century. For additional information on the Constitution, see the Independence Hall: International Symbol of Freedom lesson plan. The M'Clintock House: A Home to the Women's Rights Movement lesson plan highlights the Seneca Falls First Women’s Rights Convention of 1848.

National Archives and Records Administration/Charters of Freedom

The National Archive's Charters of Freedom website presents detailed information on the creation and impact of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. The website also includes transcripts and high-resolution digital images of the three documents.

National Archives and Records Administration, Teaching With Documents

The Teaching with Documents website includes a “Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment--Failure Is Impossible” lesson plan. The lesson is based on a script prepared for the 75th anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 1995. The cast of characters includes Abigail Adams, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Woodrow Wilson, and others.

TeachingAmericanHistory.org

This website is a project of the Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs at Ashland University, in Ashland, Ohio. The Ashbrook Center provides an academic forum for the study, research, and discussion of the principles and practices of American Constitutional government and politics.

National Constitution Center

The National Constitution Center in Philadelphia maintains a website that includes copies of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, an interactive Constitution that provides additional information on each of the articles, summaries of important Supreme Court cases, and other useful information.

Sewall-Belmont House (now the Belmont Paul House)

The Sewall-Belmont House has been the headquarters of the NWP since 1929. Its website includes background on the party and its history and an extensive photo archive.

Library of Congress, American Memory/Women’s History

This website is a rich repository of information. It contains excellent online exhibits and lesson plans about women's suffrage, as well as collections of primary sources from the suffrage movement.

For further reading

Linda R. Monk’s book, The Bill of Rights: A User’s Guide is a rich and easy-to-use source of information. It goes through each of the ten amendments that make up the Bill of Rights, discusses their background and the issues involved, and analyzes related Supreme Court cases.

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

First Amendment Freedoms

First Amendment FreedomsHow have people engaged their First Amendment freedoms throughout U.S. history?

-

Amending the U.S. Constitution

Amending the U.S. ConstitutionHow is the Constitution amended? Should the process of amending the Constitution be easier?

-

Voting Rights

Voting RightsHow is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting voting rights? What are remedies for low voter turnout?

Tags

- women's history

- women's rights

- suffrage

- suffrage movement

- civics

- lafayette park

- first amendment

- 19th amendment

- dc history

- washington d.c.

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- shaping the political landscape

- gilded age

- early 20th century

- womens history

- womens suffrage

- women leaders

- women in government

- twhplp