Last updated: May 18, 2025

Article

1913 Woman Suffrage Procession

Library of Congress

"Miles of Fluttering Femininity Present Entrancing Suffrage Appeal"

Washington Post

On March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson's presidential inauguration, thousands of women marched along Pennsylvania Avenue in a procession organized by the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, the newly-appointed chairs of NAWSA's Congressional Committee, choreographed the procession to illustrate women's exclusion from the democratic process. They insisted that the procession follow the same route that the inaugural parade would take the next day. The purpose of the committee and the procession they organized was winning passage of the Susan B. Anthony amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment reads:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

In the 35 years since the amendment was first proposed in 1878, it had only come up for a vote in Congress once and had failed. Paul and Burns were determined to bring new energy to the campaign for women's suffrage and to push for passage of the amendment.

Harris & Ewing, photographer. Records of the National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

The New Woman

Inez Milholland rode a white horse named Grey Dawn at the front of the procession. Astride the horse rather than sidesaddle, she wore a white dress, a cape, and a golden tiara with the star of hope on top. Inez was famous as an activist, speaker, and lawyer. She was also very photogenic and was known as "the most beautiful suffragist." She rode as the herald of the future, an example of the New Woman of the twentieth century. This was the generation of suffragists who challenged society's expectations of what it meant to be a woman and the restrictions those ideas placed on the way women dressed and behaved. They called themselves feminists and were fighting not just for the vote but for full equality.

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

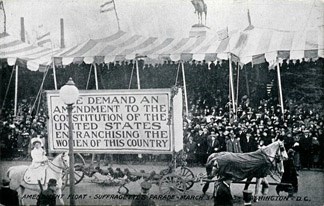

The Great Demand

Behind Inez in the procession was the first of over twenty floats. This float displayed a banner with the slogan that would become known as "The Great Demand.""We demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of this country."

Alice Paul and the other organizers were declaring a new strategy. No longer content with incremental progress, with accepting limited voting rights won in bits and pieces one state or jurisdiction at a time, this new generation of suffragists were on a mission to secure their rights to the ballot across the country under the same terms as men. They chose their language deliberately to be somewhat shocking. In the past, American women advocating for suffrage tended to do so while remaining respectable and gracious. But to demand their rights was to step out of the expectations of women as demure and gentle. The Great Demand was meant to be provocative.

Windsor McKay, artist/Library of Congress

"We march today to give evidence to the world of our determination, that this simple act of justice shall be done."

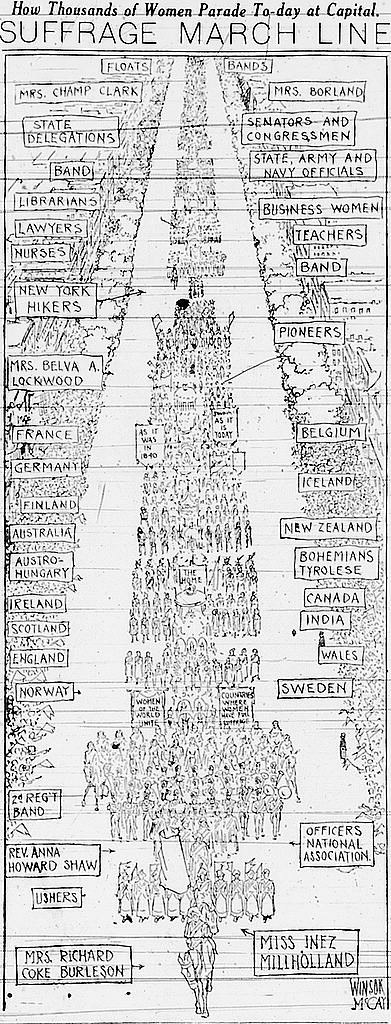

The procession was designed present an argument, section by section, about the accomplishments of women in the nation and around the world. Women marched in delegations from their states, or with others from their professions, or in their academic regalia from the universities they attended. It demonstrated that women's participation in the public sphere was dignified and in keeping with America's moral values. Behind the marchers, bands played patriotic songs and elaborate floats illustrated the beauty and competence of women.

But very few of the spectators got to see the full demonstration as Paul had envisioned it. The crowd of at least 250,000 people did not stay on the sidewalk but began to stream into the streets and block the parade route. Police stationed along Pennsylvania Avenue were unable or unwilling to control the crowds. The marchers tried their best to continue. Those in cars or on horseback tried to drive the throng of people back and clear the street, but the crowd would simply fill back in behind them. Progress slowed and then stopped.

The marchers found themselves trapped in a sea of hostile, jeering men who yelled vile insults and sexual propositions at them. They were manhandled and spat upon. The women reported that they received no assistance from nearby police officers, who looked on bemusedly or admonished the women that they wouldn't be in this predicament if they had stayed home. Although a few women fled the terrifying scene, most were determined to continue. They locked arms and faced the ambush, some through tears. When they could, they ignored the taunts. Some brandished banner poles, flags, and hatpins to ward off attack. They held their ground until the U.S. Army troops arrived about an hour later to clear the street so that the procession could continue.

Leet Brothers, photographer. National Woman's Party Records, Library of Congress

African American Women in the Procession

Black women felt like they were under attack long before the crowds descended upon the marchers. They had to fight just to be included in the procession. As described in the NAACP's newspaper:

“The women’s suffrage party had a hard time settling the status of Negroes in the Washington parade. At first, Negro callers were received coolly at headquarters. Then they were told to register, but found that the registry clerks were usually out. Finally, an order went out to segregate them in the parade, but telegrams and protests poured in and eventually the colored women marched according to their State and occupation without let or hindrance.” The Crisis, vol 5, no. 6, April 1913, page 267.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett traveled to Washington, D.C. with the Illinois delegation and fully expected to march with them. As the group was lining up to begin the procession, the white suffrage leaders suddenly asked Wells-Barnett not to march with her fellow suffragists from Illinois and instead assume a place in the back of the procession. Wells-Barnett refused and left the area. Instead, she waited along the side of Pennsylvania Avenue until the Illinois group marched by. Then she and two white allies stepped in front of the Illinois delegation and continued in the procession.

Although it is sometimes reported that African American women marched in the back of the procession, The Crisis reported that more than forty Black women processed in their state delegations or with their respective professions. Two were reported to have carried the lead banners for their sections. Twenty-five students from Delta Sigma Theta sorority from Howard University marched in cap and gown with the university women, as did six graduates of universities, including Mary Church Terrell.

"In spite of the apparent reluctance of the local suffrage committee to encourage the colored women to participate," reported The Crisis, "and in spite of the conflicting rumors that were circulated and which disheartened many of the colored women from taking part, they are to be congratulated that so many of them had the courage of their convictions and that they made such an admirable showing in the first great national parade.”

Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission. National Archives, St. Louis.

"Dawn Mist" and Native American Women

Before the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession, newspapers announced that one of the marchers would be “Dawn Mist, the beautiful daughter of Chief Three Bears of the Glacier National Park Indians.” The papers reported that Dawn Mist and her friends would ride their Indian ponies in their buckskin dresses in the parade, and camp on the National Mall in their teepees. They would “represent the wildest type of American womanhood” side by side with white women like Inez Milholland, who represented “the highest type of cultured womanhood.”But Dawn Mist wasn’t a real person.

She was a character created by the public relations department of the Great Northern Railroad. The railroad hired Native American women to perform as Dawn Mist – at least three of them. They used images of the women posing as Dawn Mist in advertising and on postcards. In 1913, Daisy Norris, a Blackfoot woman, was working in the role of Dawn Mist for the Railroad. But she wasn’t in D.C. for the Suffrage Procession. It was all a publicity stunt.

There was, however, at least one native woman in the 1913 parade. Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin marched with the lawyers contingent in the procession. Of French and Ojibwe heritage (Metis/Turtle Mountain Chippewa) she would become the first Native American woman to graduate from the Washington College of Law. She had moved to D.C. with her father to fight for tribal sovereignty and became a federal civil servant, working for the Federal Indian Bureau. She later advocated for Native American suffrage in her work with the Society for American Indians.

National Woman's Party Records, Library of Congress

The Suffrage Movement Re-energized

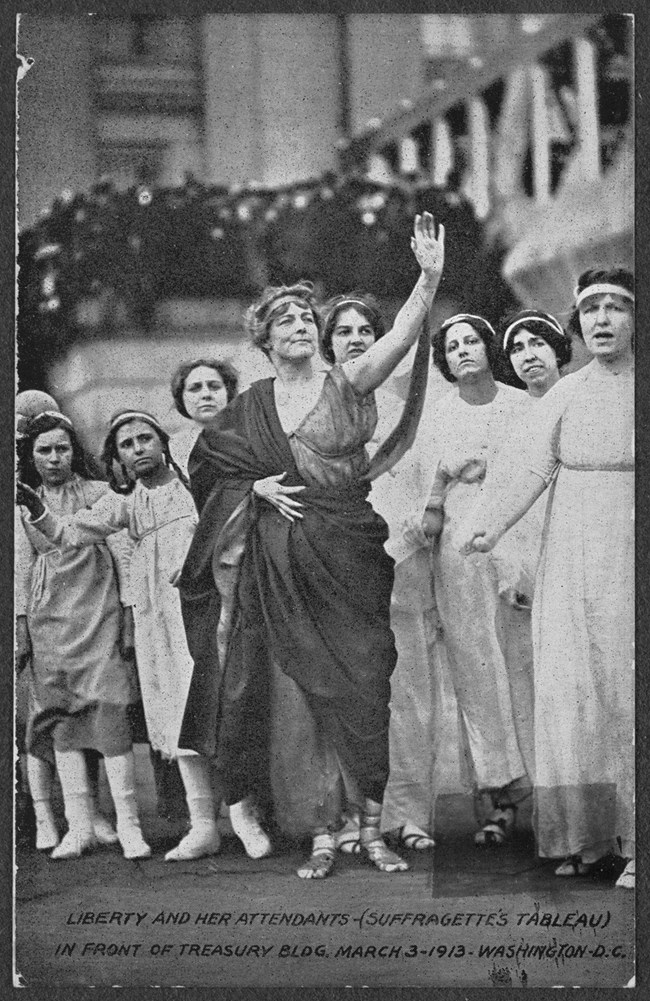

The procession ended, a hour or so later than planned, with a dramatic tableau on the steps of the Treasury Building. The next day, headlines in newspapers around the country proclaimed the drama of the Woman Suffrage Procession. The coverage of the march was often more prominent on the front pages than news of Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. Congress began an investigation to determine why crowd control by the police had been so ineffective. The hearings kept the procession in the news even longer. Although the Washington, D.C demonstration was not the first suffrage march or the largest, the publicity it received brought new attention and energy to the movement, energy that would eventually push the 19th Amendment through Congress.

L & M Ottenheimer, Publisher/National Woman's Party Records, Library of Congress

Sources:

Cahill, Cathleen. Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement. UNC Press, 2020.Rabinovitz-Fox, Einav. "New Women in Early Twentieth-Century America." Oxford Research Encyclopedias, August 2017.

Ware, Susan. Why They Marched: Untold STories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2019.

Zahniser, J. D. and Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. Oxford University Press, 2014.