Last updated: December 15, 2020

Person

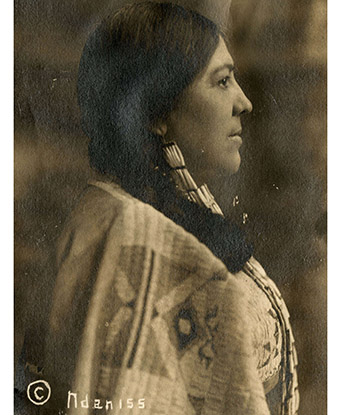

Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin

Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission. National Archives, St. Louis.

Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin (Metis/Turtle Mountain Chippewa) was born in Pembina, North Dakota. Her father, J.B. Bottineau, was a lawyer who worked as an advocate for the Ojibwa/Chippewa Nation in Minnesota and North Dakota. While a teenager, her family lived in Minneapolis, and Marie attended school there as well as in nearby St. Paul. She spent some time across the border at St. John’s Ladies College in Winnipeg, Manitoba (Canada), and returned to Minneapolis to work as a clerk in her father’s law office. She and her father moved to Washington, DC in the early 1890s to defend the treaty rights of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Nation. There, they became part of an established community of professional Native Americans who lived and worked in the capital.

In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Marie as a clerk in the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), an agency within the Department of the Interior.[1, 2] She was hired at $900 per year, and received a raise to $1,000 before she had served a full year in the position. While this pay was low compared to what other clerks were making ($1,000 to $1,800 per year), she was the agency’s highest paid Indigenous woman.

Early in her career, Marie believed that Native Americans needed to assimilate into European-American society to survive. Over time, as she became involved with the suffrage movement and the Society for American Indians (SAI), her views began to change. Instead of assimilation, Marie emphasized the value of traditional Native cultures while asserting her own (and therefore others’) place in the modern world as an Indian woman.

This shift is evident in a ca. 1911 photo of Marie. Taken for her government personnel file, she chose to wear Native dress and to braid her hair. This was a radical act as a federal employee working for the OIA. At the time, was pushing for Native Americans to assimilate into white American culture-- and using Indian employees as examples of assimilation. And yet, her choice went unremarked at the time -- except by journalists, who often paired her federal service photo with one of her dressed in “modern American dress.”

In 1911, Marie’s father died. His death proved a turning point in her life. That year, she gave a speech at the first meeting of the Society of American Indians, and became increasingly involved in their work to celebrate and advocate for Native identity. She became nationally known as a spokesperson for modern Indian women, testifying in front of Congress, meeting with women from across the country, and was a member of the contingent who met with President Woodrow Wilson in the Oval Office in 1914. While at the SAI, she was colleagues with Zitkala-Sa, another Native American woman who worked towards Indian suffrage.

In 1912, at the age of 49, she enrolled at the Washington College of Law. Two years later, after taking night classes while still working, she graduated as an attorney. Marie was the first woman of color to graduate from the school.[3] She became active with the suffrage movement in Washington DC and marched with a group of other female lawyers in the 1913 Suffrage Parade organized by Alice Paul. Interviewed in newspapers who were covering the suffrage movement, Marie educated people about the traditional political roles of women in Native society.

Changing politics and priorities within the OAI led to Marie disengaging from the group in 1918 or 1919. She continued to work for the Indian Office in Washington, DC until 1932, when she retired for health reasons. In 1949, she moved from DC to Los Angeles, where she died from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1952. She is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, Los Angeles, California.

Notes:

[1] The Office of Indian Affairs changed its name to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1947.

[2] When Marie began her work for the Office of Indian Affairs, the Interior Department was headquartered in the Old Patent Office building, which currently is home to the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum. Bounded by F and G Streets and 7th and 9th Streets NW in Washington, DC, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on January 12, 1965. From 1917 until 1936, the Interior Department headquarters was in what is now the General Services Administration Building at 18th and F Streets NW, Washington, DC. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 23, 1986. The Department of Interior is currently located at 1849 C Street NW, Washington, DC, a building added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 10, 1986.

[3] Washington College of Law was started in 1896 by Ellen Spencer Mussey and Emma Gillett in Mussey’s law offices when a handful of women asked to study with them -- traditional law schools refused to admit women. It was the first law school founded by women, the first with a woman serving as dean, and the first to graduate a class of all women. They merged with American University in Washington, DC in 1949. In the beginning, the law school accepted only white applicants. Marie Bottineau Baldwin graduated in 1914. The school graduated their first African American student in 1953.

References:

Barkwell, Lawrence J. 2014. “Bottineau-Baldwin, Marie Louise.” Virtual Museum of Metis History and Culture, January 13, 2014.

Cahill, Cathleen D. 2013. “Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin: Indigenizing the Federal Indian Service.” American Indian Quarterly, 37 no. 3: 65-86.

US Civil Service Commission. Personnel File Photograph of Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin; ca. 1911; Marie Baldwin; Official Personnel Folders-Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs; Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, Record Group 146; National Archives at St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.