Contact Us

Cult of True Womanhood

Back to the And Nothing Less Series Home

To understand what the suffragists were up against, we have to look at why men -- and even some other women -- didn't want women to have the right to vote at all.

Hosts: Rosario Dawson and Retta

Guests:

- Martha Jones, professor of history at Johns Hopkins University and the author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All

- Elaine Weiss author of The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

-

Allison Lange, professor of History at the Wentworth Institute of Technology, consultant to the WSCC

-

And Nothing Less: Episode One "Cult of True Womanhood"

To understand what the suffragists were up against, we have to look at why men -- and even some other women -- didn’t want women to have the right to vote at all.

- Credit / Author:

- PRX, WSCC, NPS

- Date created:

- 08/05/2020

[Music fades up]RD: It’s August 18, 1920. There’s an up and coming young Tennessee legislator named Harry T. Burn. He is, in fact, the youngest member of the state house.

He didn’t know it when he walked to the state house that morning, but his aye or his nay would be the deciding one when it came to protecting the right to vote for millions of women in the country.

R: You see, the fight for a federal law, one that would guarantee voting rights for women on a national scale...a fight that lasted more than 70 years, multiple wars, and yes, even a pandemic...it came down to Tennessee.

RD: The suffragists needed three-fourths of the states to vote in favor of the 19th amendment in order for it to be ratified. The lucky number was 36. And by the middle of 1920, they had 35 states secured. That left one more. And they set their sights on Tennessee.

R: For weeks, lobbyists from both sides camped out at the Hermitage Hotel in Nashville wearing their respective flowers -- yellow roses for the women’s rights crew. Red for the anti-vote folks. It was, ahem, the War of the Roses.

RD: Finally on the day of the vote, Harry T. Burn shows up with his own flower in his lapel -- the color of blood.

So he had made his decision after all. And it seemed like the anti-suffrage contingent had enough nays to delay voting on the amendment entirely.

R: But, in a surprise move, another representative switched his vote. And so the 19th amendment decision was sent forward for a vote.

This meant that Harry T. Burn, representing his conservative East Tennessee district, was forced to finally make a decision. His shocking answer was “Aye.”

Because, while he had a red flower on his lapel, he also had a letter in his pocket. And that letter was from his mother. Earlier, Febb. E Burn wrote to her son and asked him to be “a good boy” and vote for women. RD: He later explained that he expected the ratification vote to be off the table entirely and pushed to a whole other legislative session. But once his hand was forced, he said quote “I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.”

Burn then added: “I appreciated the fact that an opportunity such as seldom comes to a mortal man to free 17 million women from political slavery was mine.”

[Music flourish/ending]

RD: It’s pretty amazing to think that had Burn looked down and smelled the red roses instead of listening to his mother’s words, history would’ve been very different.

R: But this is a story about more than just one man being a good boy.

RD: This is a story about many, many women

R: And men!

RD: acting in brave and radical ways. And this is a story about democracy.

Weiss: when we talk about the women's suffrage movement, the seven decade campaign, we're talking about democracy

Elaine Weiss is the author of a suffrage history called The Woman’s Hour. Fun fact...it’s being developed for TV by someone whose name rhymes with Peevan Peelberg. In other words, she knows a lot about this. Weiss: you have to imagine that for about 150 years, the United States did not consider women, half of the population to be full citizens, full participants in deciding the course of the nation, deciding who represented them, deciding how the nation and their town and their city and their state was governed. So we're talking about the largest enfranchisement of a population without a revolution. And we're talking about half the nation not having the vote and then having to fight bitterly to get the vote.

RD: Now 100 years later, on the anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment, we get to celebrate a win for women and a win for democracy.

R: Rosario, you know, I’m recording this from my house. What about you?

Rosario: Oh, yeah. I'm In my closet. Basically. Retta: I'm in my closet. The only quiet room.

R: A few months ago, this was not how any of us imagined we’d be doing our work. Or having our celebrations. Whether we’re talking about zoom birthdays or a suffrage centennial. On the upside, I don’t know about you, but I feel the need for community now, more than ever.

Rosario: Oh. Oh, same. I mean, for my sanity sake, trying to stay as present as possible and trying to just be in my gratitude. So I'm just not so overwhelmed. What's gonna happen next? 2020 doesn't seem to be pulling any punches. So... Retta: And I need a pedicure. Rosario: You know, I think it's really easy just to get kind of lost in fear about the future. And I think that's the solace that I get in looking to history in the past to kind of make me feel less alone and to give me more context and perspective to where we are within the movement's history. R: But the risk of all the worrying about the future is forgetting about the past. Like, is there an urgency to this history?

RD: Well, we think so. martha: The story of the 19th Amendment is only one chapter in the long history of voting rights in the United States. martha: Today we live in another chapter, if you will, of the same story. So for a lot of us, coming back to the story of the 19th Amendment is a reminder about how we got where we are today. RD: That’s historian Martha Jones.

So this anniversary is an opportunity to bring this history to audiences eager to know the “whole story.” And that story is best told as part of a longer tale. One that talks about America’s relationship with the vote, with gender and with race. And of course, one that shines a light on the people that fought for the right to be counted. Because they weren’t granted anything.

R: So let’s get started. we’ve got a lot to cover and only 7 episodes to do it ---

Theme music

RD: I’m Rosario Dawson

R: And I’m Retta. And this is “And Nothing Less: The Untold Stories of Women’s Fight for the Vote”

This is Episode One, The Cult of True Womanhood

THEME Rosario: I love our theme music because we are here to celebrate our right as women to vote yes, which is huge. Retta: OK. Can I just tell you... that for the longest time I didn't know what suffrage meant. I know it was associated with voting, but I didn't know exactly what it meant. Rosario: I mean, we're unfortunately not taught that very well. And for everyone, suffrage is basically the right to vote. But I'm curious, what did you learn about women's suffrage growing up? Retta: From what I remember, it was just wealthy white women. For some reason in my head, they were all tall. They wore these like pilgrim-y white shirts, big hats, long, dark, heavy skirts. When I think about it now, it's obviously because the pictures were in black and white. They marched and then I knew that they would be jailed and they wouldn't eat. And somehow that worked to get women the right to vote. And now, for me, voting, voting is a big deal. It was important that I get to the polling station early. I'm a six a.m.-er. I am not to be standing in anyone's line all day. I don't want to have to fight anybody over how hot and annoyed I am. So I'm there 6:00 a.m. with the older neighbors and we get our stuff in and out with a quickness. Rosario: For me, the thing I think that I always brought to it was my grandmother, my grandmother, I saw as the suffragette in my head this woman who had like permanently curved feet because she wore high heels so much she used to vacuum with heels on, you know, and she, being Puerto Rican, knew that she had limited rights even as a woman capable of voting there. So even going beyond that and being in the states, she took it really seriously that she had a voice, that it wasn't just supposed to be her husband that was supposed to speak up for the family, but that her experience, her wisdom, her wants, her needs, her passions could be represented and counted as well. So, you know, my grandmother was want to say often I may speak with an accent, but I don't think with one. So she voted religiously. And it's because of that that I've taken this so seriously as a woman now. And maybe I take for granted that it's my right, my just innate right to count and to be heard and to participate. But that wasn't always the case. And it's kind of curious to think about why, like, how was this such a big deal like. What did they think would happen when women got the right to vote? R: Yeah...It’s not like letting a woman touch a ballot was going to topple the republic. Or was it? allison lange: Even today, people are afraid of changes. And They were afraid of this change. R: Allison Lange is a professor of History at the Wentworth Institute of Technology who specializes in the images of the women’s voting rights movement. And it turns out - that people in the 19th and early 20th century DID worry about women toppling the republic. Or worse. Allison Lange: They're afraid that if women take on masculine tasks like voting and speaking out in public and running for office, that men will actually become more feminine, that they will have to take on domestic chores. So they don't want to see this change in family life at all. You know, like in political cartoons, one of the, like, signs of the apocalypse is like a man carrying a baby. [music] RD: Not surprisingly, in the 1800s, it was women who were supposed to be carrying the babies. And this feminine ideal was shaped by the quote - “cult of true womanhood.” R: Probably not any cult we would join today. RD: It basically said that women were safest in the homes, away from the sullying influences of business and public affairs. Women were, of course, not suited for hard labor or politics, but safely in their abode, they were quite useful to exert their serene moral influence over their husbands and children. R: Ah serenity now…[relaxing sounds] But before we get too comfortable on our fainting couches, we should probably talk about what was happening at this point in history that was so, you know, sullying. RD: But brace yourself...we’re talking about 70 years of American history --- there's a lot to unpack here. And Elaine Weiss explains...it starts long before the Civil War... Elaine Weiss: In fact, that's the time of the Mexican war. Weiss: And if we mark it from the sort of middle of the 19th century and the women's rights movement emerging side by side with the abolition movement. And I think that's a crucial point that the women we know as the foremothers of the suffrage movement, women's suffrage, are actually begin their political careers as abolition workers and they’re working side by side with Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Things get a little messy during the reconstruction movement. And they go through several wars, including the Great War, World War One. They go through many recessions, depressions, labor strife, the progressive movement. And all of these historical moments really do impact the movement. Weiss: It's not like women's suffrage exists on a separate plane or in a little bubble. It is buffeted by all of the political and social and economic winds that strike it during these seven decades. Weiss: You’d think -- Well, they begin in the mid 19th century. It should be done in a few years, and it's certainly not. And some of the reason is the political forces, the historical forces at work, even the economic forces. And it's also about changing hearts and minds, how long it takes to change social ideas about women's role in society. RD: Changing ideas about what role women should have in society, well that was going to be almost as hard as changing policy. And these were ideas that Allison Lange says Americans were seeing everywhere -- in newspapers, magazines and ads.

allison lange: Really the common theme for the ideal woman of that time was to be someone who was really focused on the home, on family life.. And She was in a wealthy enough family to allow her to stay home and focus on her house and her children. She was a very particular type of woman. And, you know, much like the ideals we have today, they're achievable by only particular parts of the population. RD: Lange says people might be surprised to hear that one such idealized woman that could’ve received cult membership was Martha Washington. allison lange: she was probably the most recognizable American woman throughout the 19th century. And in fact, she is the first and only, as of 2020, woman to actually appear on our paper money and her portrait was on our paper money in the eighteen eighties. And she was really held up by Americans as this ideal for supporting her husband, for running his, you know, political events, acting as a really important society hostess and being a caring mother to her children as well. So she was in the 19th century, kind of the most famous first lady for sure. RD: When you think about this feminine ideal, you realize there was nothing realistic about it. Even in the wealthiest families, women were working, when you take domestic labor into consideration. And, with the industrial revolution many women had entered the factory labor force, as well as boarding houses and taverns. This cult of true womanhood also offered no membership to the millions of enslaved black women who were working in the south. Or even to the black women who were able to win freedom.

R: But women were able to find membership, if you will, and a sense of community in clubs. allison lange: Sometimes these were temperance societies, so anti alcohol societies. Other times they were to help women they considered fallen -- so women who were perhaps prostitutes, to kind of help them re-enter society and support them throughout that process. Helping children, helping poor people. All of these kind of benevolent moral reform associations were extremely popular among women by the 1830s. Women are joining more clubs, and this is a way to participate in their communities, participate in politics in a way that they otherwise just really didn't have access to. R: The birth of the club movement meant that as women were starting to think about their own rights and the rights they wanted to win on behalf of others, they were becoming bosses.

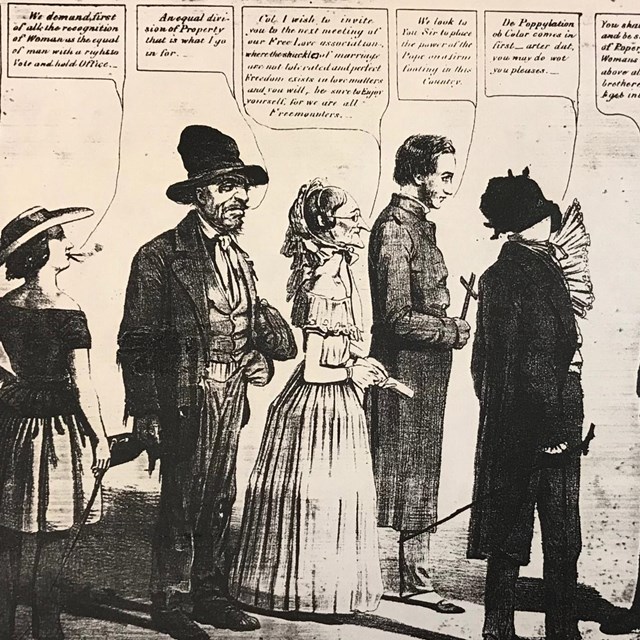

allison lange: They knew how to run a meeting. They knew how to give a lecture. And so all of those components means that by the late 1840s, when we have this meeting in Seneca Falls in 1848, these women are well equipped to start a movement. R: Though how equipped would they be to combat a fierce movement rising against them? Just as images of a delicate flower at home were popular at the time, so were anti-suffrage images. Imagine the most annoying meme, but with political power.

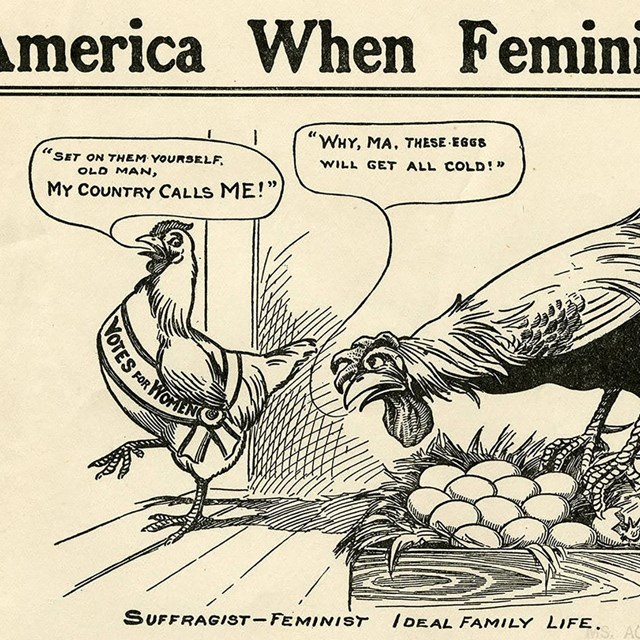

Weiss: And there are all these anti suffrage illustrations of a pair of pants saying, well, what are men going to wear when women wear the pants in the family?

R: Elaine Weiss remembers quite a few of these. Weiss: one of my favorites is something a broadside called America When Feminized. And it shows rooster and a hen. And the hen is wearing votes for women sash. And she's just walked off the nest and the rooster calls after and says, Mom, the eggs are going to get cold. And she calls back. Sit on em yourself, old man. My country calls me. And one of the taglines underneath is a vote for the federal suffrage amendment, which is the 19th Amendment is a vote for organized female nagging forever. [music] RD: So you get a sense that for certain Americans, the vote was not just going to upset public life, but their private lives too.

RD: And in a time before social media, and before sound bytes, images like these held enormous political capital, says Allison Lange.

allison lange: “Most of the popular publications that Americans read throughout the country really just had a lot of cartoons that portrayed suffragists as masculine women who are abandoning their families, who were challenging social norms, who were acting aggressively and just entirely disrupting society. And the goal of these pictures, which was to make people laugh. Right, to make fun of the suffragists who's wearing a top hat and boots with big spurs on them and a very short skirt in that time period. These are these stereotypes that are very hard to change.

RD: Suffragists would gradually learn how to fight back when it came to visual propaganda. And their own mass media campaign would present a more appealing woman suffragist: a non-threatening, wealthy, white woman.

RD: The image had little to do with the women they were fighting for. Some suffragists refused to conform to notions of how a woman should act, live, and love.

But it’s clear, even then, images were political. And some historians will argue that in time, the image of the feminine suffragist would start to reflect the dominant political agenda...with the 19th amendment only serving that one ideal of womanhood.

R: That said, while suffragists were putting a more palatable spin on their image, their ideas were no less radical. They were looking for more than just the right to enter a voting booth. They were looking for justice, and frankly, power. And you can bet that was threatening.

Weiss: Oh, it was very scary. Weiss: there are those for whom it is a moral outrage. They truly believe that women demanding equality with men goes against what they call God's plan. And to question that is really to question the tenants of the Bible. So that's a big hurdle to have to overcome. Weiss: then there's those who truly believe that women, if they are able to vote, able to express political opinions in any way, are going to be distracted and will actually abandon the home. And the idea is that a woman should have no other role than wife and mother. And if she becomes interested in politics or able to have an equal vote with her husband, what is she going to demand next? R: Depending on who you ask, says Elaine Weiss, these are either extremely outdated ideas, or still pretty relevant. R: You’re listening to And Nothing Less. Let’s take a quick break. [Theme Music]

--- BREAK

--- [music]

R: I’m Retta and...

RD: I’m Rosario Dawson. It’s Episode One of And Nothing Less.

R: And you know what, while we’re mentioning that title...you’re probably wondering what that means.

Well back in 1868, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton published a newspaper called the Revolution.

RD: I love that name.

R: It only lasted a couple of years, but it’s influence was pretty wide-reaching. It published articles and editorials on things like divorce and prostitution. And listen to its motto:

RD: "Men their rights and nothing more; women their rights and nothing less."

R: That idea - that women should settle for nothing less, nothing less than equal rights, nothing less than complete justice, nothing less than total representation...well, that goes far beyond just Anthony and Stanton. And it’s one we’re gonna keep in mind throughout the show.

RD: So let’s continue. The fight for suffrage lasted a really long time. Well over seven decades.

R: And that means that the fight against suffrage lasted for equally as long. And it’s worth giving these opponents - or “anti-suffragists” - a closer look.

RD: The anti-suffs ranged from big businesses, like the railroads and liquor lobbies, to states and governments not ready to give up power, to, of course, everyday Americans.

R: Let’s look at one big area of contention. This is both within the suffrage movement and among the people who wanted to block the vote: That’s the 15th amendment.

R: Now, this of course is a podcast about a constitutional amendment, but Rosario, I’m sure not an expert. Are you?

RD: Nope!

R: Well, you don’t need to be. But here’s what do you need to know:

[music]

R: When it comes to the Constitution there are a couple of ways amendments can be added. But the most common is that Congress passes an amendment, and then it goes to the states for ratification. You need three-fourths of the states to vote to approve it. This hurdle is a big one for the 19th amendment.

So anyways, after the Civil War and the end of slavery, there were three amendments passed between 1865 and 1870. They’re known as the “Reconstruction Amendments.”

You with me so far?

RD: I’m with you.

R: Well the first of these Reconstruction Amendments is the 13th. It essentially abolished slavery. The 14th Amendment defined national citizenship. It made clear that people who were once enslaved were now citizens of the country and deserved their rights as citizens. And there’s something really important in the second section of the 14th Amendment. It contains the first reference ever in the Constitution to gender. This section defined whose right to vote would be protected -- male citizens over the age of twenty-one. This made it explicit that only men’s right to vote deserved protection and left the door open for states to deny women certain rights. RD: But what about the 15th Amendment? R: Well that stated that the right to vote could not be denied on account of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” It established that Black men had the right to vote -- though of course states found ways to suppress those rights. What the 15th Amendment didn’t do was establish that the right to vote could not be denied on account of sex, as well. And so when it was proposed and then adopted in 1870, there was a lot of controversy within the suffrage movement. So keep all that info in your back pocket RD: Ok, got it. [end music] R: Now here we are at the end of the Civil War during Reconstruction, and the right to vote is back in public debate. This is a turning point for the suffrage movement and those who are fighting it, according to Allison Lange. allison lange: After the Civil War, Americans debated what should happen in American politics and the debate over the 15th Amendment kind of brings suffragists into the conversation, and they're trying to argue that now after the civil war, women should have the right to vote. Ultimately, they decide to pass the 15th Amendment, which says that voting rights cannot be prohibited based on race. R: Voting rights can still be prohibited on the basis of sex. This divides the women’s rights movement. And the anti’s pick up on this.

RD: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony are in one camp. They want all women to be included with black men. Wanted maybe isn’t a strong enough word?

R: “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman,” Anthony said.

[Hosts react]

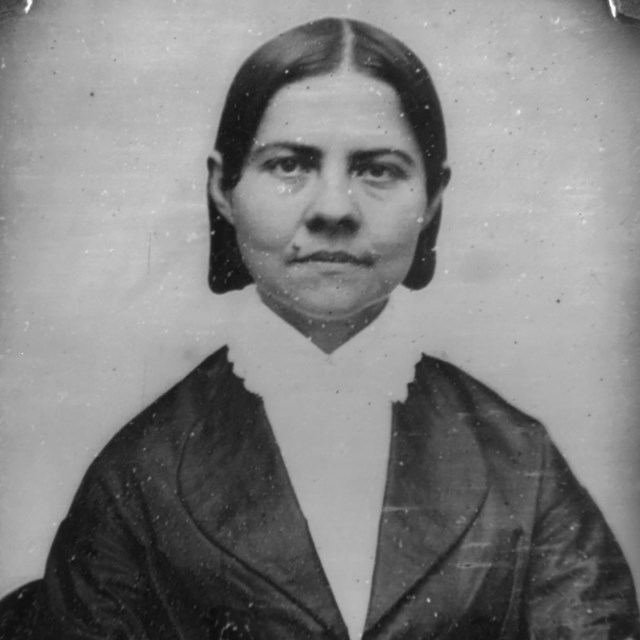

RD: Other activists like Lucy Stone, who founded the American Woman Suffrage Association, defended black men getting the vote as a first step and believed women would get there soon enough.

R: And some Americans didn’t approve of rights for women or Blacks. The vote was a common enemy, says Elaine Weiss. Elaine: racism becomes a very big part of the anti suffrage campaign. And you see kind of barely coded language of the anti-suffragists saying this is going to make black women able to vote. And perhaps black women will even feel that they are socially equal, and this will undermine the southern way of life, which, of course, is code for white supremacy.

RD: Anti-suffragists would continue to chafe throughout Reconstruction. More federal authority meant more power for individual citizens. First came men...were women next?

R: They had reason to fear. In 1869 and 1870, two territories passed laws giving women the right to vote: Wyoming and Utah. And a few years later there would be debates over women’s suffrage in Congress. And oh boy did the Anti-suffs come out in full force.

Reading (clear throat)”

R: “To the Honorable Committee on Privileges and Elections. Gentlemen - Allow me, in courtesy, as a petitioner, to present one or two considerations regarding a sixteenth amendment, by which it is proposed to confer the right of suffrage upon the women of the United States.”

RD: That’s a quote from Mrs. Admiral John A. Dahlgren. If she were writing today, she might use her own name, Madeleine. It’s a letter drafted to the Senate in opposition to a proposed women’s suffrage bill in 1878. In it she explains that the harmonious family is “the foundation of the State.” She adds that “Out of this come peace, concord, proper representation, and adjustment—union.” And that “Enfranchising all citizens would excite competing interests within the family and society and render “discord” the “corner-stone of the State.”

R: It’s hard to imagine women were worried about a vote threatening their family, let alone their state. But these were deeply felt, explains Allison Lange.

allison lange: women who were advocating against granting women the right to vote had a range of reasons why, one being that they really believed that women as caregivers, as domestic homemakers, were in a protected special, very privileged role, By being able to take care of their homes and families rather than deal with politics. They really subscribe to that belief. You know, it wasn't just an ideal for them. It was something that they truly valued. They believed that their fathers, that their husbands, that their sons all voted in their best interests. And so if these men are voting in your best interest and you truly believe that, then why would you need to go to the polling station and cast a ballot, too? So one argument was that women would simply just cast ballots the same way their husband did. And therefore, we'd just be doubling the expense of voting. And so why would we choose to do that?

RD: As the 1800s wrapped up, the weight of Reconstruction became less heavy. But suffrage met some new opponents. Women’s rights were linked to a host of other political issues and reform causes -- immigration, and marriage rights, labor and temperance

R: Which means abstinence from alcohol.

RD: Exactly. Caroline Corbin was a reformer in the late 1800s and early 1900s dedicated to temperance, Christianity, and social unity. She was also extremely anti-suffrage. Born on the east coast, she moved to Chicago after marriage and was a member of the Women’s Temperance Alliance.

Now the majority of temperance organizations at the time were actually pro-suffrage. And the connection was a direct one. The idea was that drinking led to violence against women and poor conditions for women and children. Eliminate it and you protect the home. The right to vote would give women even MORE ability to protect the home.

RD: But for Corbin, women’s rights meant men were no longer obliged to protect the family. And that tossed out the entire social order.

R: There was, however, another social activist in Chicago working at the same time who saw things much differently.

R: Jane Addams didn’t fear change. The Hull House founder was in search of a modern utopia, one that’s industrial, full of immigrants and has the capacity to regulate all that can corrupt a city, like poverty, disease and politics. And it was up to women, the moral authority, to reach that utopia.

allison lange: So in the 19th century and even into the 20th century, women were considered to be more moral, more virtuous, purer gender and in American society. So they are the ones that are kind of spearheading these moral reform societies. They're doing everything from trying to end prostitution to supporting the poor. Any kind of charitable effort is part of this moral reform society. And this is really hand-in-hand with the temperance or anti-alcohol movement that's extremely popular throughout the 19th century. Women are fighting for temperance because they do not like the fact that a lot of times drunk spouses, husbands could physically hurt their wives, their children. They didn't like that the fact that women didn't have control over their money and their and their husbands might just choose to spend it on alcohol or whatever they wished. They believed that it was detrimental, perhaps even against religious beliefs. RD: So we’re getting a sense of what the suffragists were up against. And what was happening in the U.S. and around the world during the 19th and early 20th century. You can start to see why some women were feeling the urgent need for the right to vote. While at the same time other organizations, like the Nebraska Men’s Association are sending around pamphlets describing women as “admirable and adorable”...

R: Oy vey (Oh geez / insert response of choice)

[theme Music drums starting]

RD: I know, I know. Which I am. But I should still have the right to vote! But we don’t get that until 1920. sally: no, 1920 was not when women first got the vote R: Wait, what now?

RD: Is that true?

R: I have a feeling there’s a lot we’ve been taught wrong about this story.

RD: Next time...we roll up our sleeves and get to some serious fact checking. I’m Rosario Dawson.

R: and I’m Retta And this is And Nothing Less.

[CREDITS]

This was And Nothing Less, from the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission, the National Parks Service, and PRX. This podcast was envisioned by W-S-C-C Executive Director Anna Laymon with support from Kelsey Millay.

The production team is Executive Producer Genevieve Sponsler, Producer & Audio Engineer Samantha Gattsek, and Writer & Producer Robin Linn. Our music is by Erica Huang with additional music from Epidemic sound. The historical content used to create these stories was brought to you by the National Park Service -- teachers can download companion lesson plans at go dot N-P-S dot gov slash suffrage podcast.

For even more suffrage history, visit the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission at womensvote100 dot org. [PRX AUDIO SIGNATURE]

-

And Nothing Less Extras: Suffrage Cat

Join Retta and Rosario Dawson as they discuss the connection between women's suffrage and the cat.

- Credit / Author:

- PRX, WSCC, NPS

- Date created:

- 08/05/2020

The Suffrage Cat (Episode 1)(RD & R: Banter back and forth about cats ---)

R: How many cats is too many cats?

RD: ….one cat is too many. (Or maybe she says three?)

R: [Agrees or disagrees] BUT, love em or hate em, cats have always been part of suffrage history.

RD: If you look at postcards and cartoons from the suffrage era -- and there are great exhibits of some of these right now, we’ll link to them on our show notes -- the cat was everywhere!

R: Anti-suffrage groups used cats in their propaganda against the women’s rights movement, comparing suffragists to cats. This happened both here and in England. Basically the idea was that a woman voting was as absurd as a house cat voting.

The cat also was used to symbolize something feminine. So some cartoons would show the potential risks of women in power. I’m talking - men at home, with a cat, doing the laundry and taking care of babies. He’s looking at the viewer like, what a sucker I’ve become, domesticated like this house cat.

RD: And so, if they were going to win back the public’s favor, and cat lovers, the suffs had to take the symbol of the cat and rebrand it.

Two suffragists named Nell Richardson and Alice Burke began to reclaim the cat during a cross-country road trip in 1916. They invited the press to send them off in New York City before hitting the road. Nell and Alice, in a tiny, yellow, two-seater called a Golden Flier, depart for Ohio, Texas and other states before ending in Washington and California. And along for the ride was a mascot -- a little black kitten called Saxon, named for the company that made the Golden Flyer.

Listener Companion from the National Park Service

Find out more about the people, places, and stories from Episode One.People

-

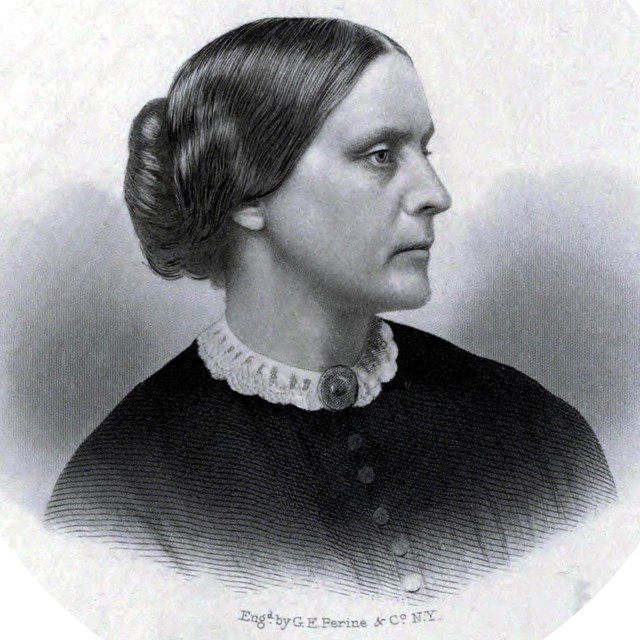

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. AnthonySusan B. Anthony was a suffragist, abolitionist, and activist for women's rights.

-

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady StantonOne of the driving forces behind the First Women's Rights Convention in 1848

-

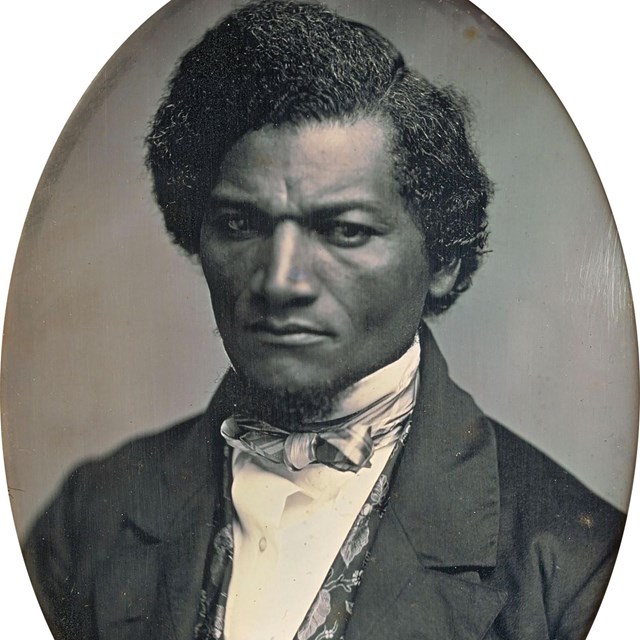

Frederick Douglass

Frederick DouglassFrederick Douglass, formerly enslaved, was an abolitionist, suffragist, publisher, and author.

-

Harry T. Burn

Harry T. BurnIf it wasn't for Harry T. Burn and his mother, the 19th Amendment would not have been ratified in Tennessee, and possibly failed altogether.

-

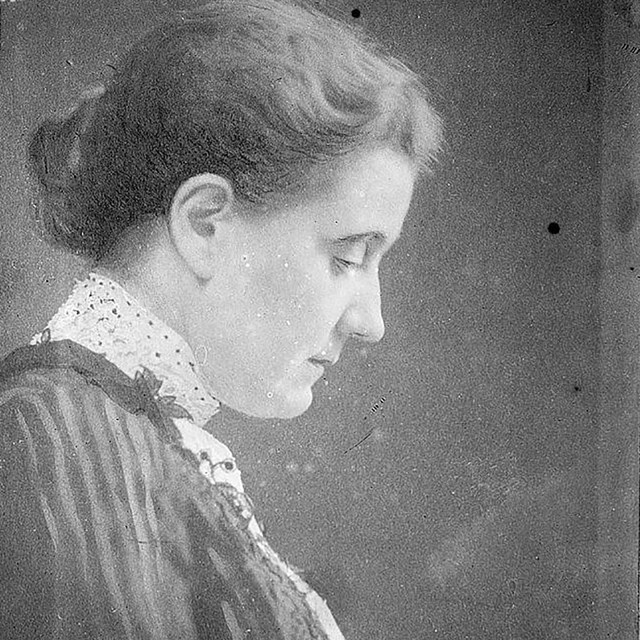

Jane Addams

Jane AddamsJane Addams was a suffragist, social activist, and author.

-

Lucy Stone

Lucy StoneLucy Stone worked to end slavery and argue for the rights of women. She founded the American Woman Suffrage Association.

Places

-

Hermitage Hotel, Nashville, Tennessee

Hermitage Hotel, Nashville, TennesseeDrama and intrigue filled the Hermitage Hotel in Nashville leading up to the vote that would decide the fate of the 19th Amendment.

-

Wesleyan Chapel, Seneca Falls, New York

Wesleyan Chapel, Seneca Falls, New YorkThe 1848 Women's Rights Convention was held here at the Wesleyan Chapel.

-

Tennessee and the 19th Amendment

Tennessee and the 19th AmendmentFind out more about Tennessee and the 19th Amendment.

Images

-

"America When Feminized"

"America When Feminized"View the anti-suffrage advertisement, "America When Feminized" at the Tennessee Virtual Archive.

-

Cartoon by Nina Allender, 1916

Cartoon by Nina Allender, 1916View the 1916 cartoon by Nina Allender, "Hat in the Ring" at Wikimedia.

-

"When Anthony Met Stanton"

"When Anthony Met Stanton"View this photo at the Library of Congress of Susan B. Anthony being introduced to Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Seneca Falls... in 1851.

Readings

-

African American Women and the 19th

African American Women and the 19thLearn about the important role of African American women in the struggle for the 19th Amendment.

-

The Necessity of Other Social Movements

The Necessity of Other Social MovementsLearn about the key role of other social movements to the US struggle for woman suffrage.

-

Anti-Suffrage in the United States

Anti-Suffrage in the United StatesLearn about the anti-suffrage movement in the United States.

Embed Video

- Duration:

- 32 seconds

Listen to Retta and Rosario discuss what they learned in school about women's suffrage. (Open captioned)

About the Podcast

Credits:And Nothing Less was envisioned by WSCC Executive Director Anna Laymon, with support from Communications Director Kelsey Millay. Executive Producer: Genevieve Sponsler. Producer and Audio Engineer: Samantha Gattsek. Writer and Producer: Robin Linn. Original Music: Erica Huang. Additional Support: Ray Pang, Jocelyn Gonzales, Jason Saldanha, John Barth. Marketing Support: Ma’ayan Plaut, Dave Cotrone, Anissa Pierre. Booker: Amy Walsh. Logo: Stephanie Marsellos.

Original Airdate: August 5, 2020

Last updated: October 5, 2020