|

Hale o Keawe Restoration

Left image

Right image

Stories of Preservation: Hale o Keawe

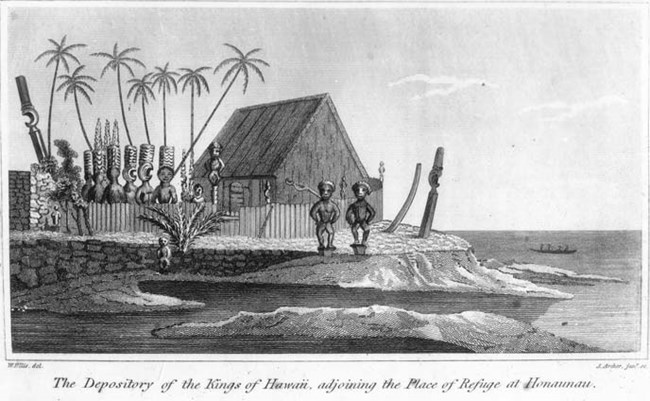

PUHO Archives Hale o Keawe, located at the northern end of the eastern wing of the Great Wall, is the only representation of a traditional hale poki (consecrated house) on the island. In ancient times the heiau served as a royal mausoleum, housing the remains of 23 deified high chiefs or aliʻi, including Keawe-i-kekahi-aliʻi-o-ka-moku, the great-grandfather of Kamehameha I. The powerful mana (divine power) associated with these bones served to sanctify and validate the existence of the Puʻuhonua. While the original structure was destroyed and the bones removed, the immense mana still remains. Native Hawaiians still revere this place and sometimes leave hoʻokupu (offerings) on the lele (tower). Genealogies and traditional accounts indicate that Hale o Keawe was likely built either by or for Keawe-i-kekahi-aliʻi-o-ka-moku around A.D. 1700. The earliest western accounts indicate that in the 1820's the structure was largely intact with thatched hale, wooden palisade, and multiple kiʻi. This indicates that even after end of the kapu system and the general destruction of heiau throughout the islands, Hale o Keawe survived largely unscathed, and continued to function as a royal mausoleum. Journey to Restoration: The Heiau Platform

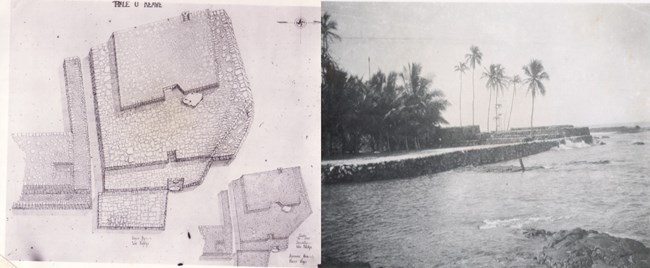

NPS Archive Photos The journey to restoring the Hale o Keawe heiau began in 1902 when the platform was rebuilt under the direction of W. A. Wall. Not much is known about the decision-making process in this restoration, only that it resulted in a reconstruction consisting of four terraces, like a truncated pyramid, and a passage between the southern end of the platform and the northern end of the Great Wall.

NPS Photos In 1966-67 Edmund J. Ladd directed the excavation and restoration of the Hale o Keawe platform. Eye-witness historical accounts and drawings indicated that the platform was smaller and did not originally have multiple tiers. Ladd's work revealed the original, smaller platform covered by the 1902 restoration. Therefore, the 1967 work restored the platform to its more authentic form that joins the Great Wall on its south side. Journey to Restoration: The Kiʻi

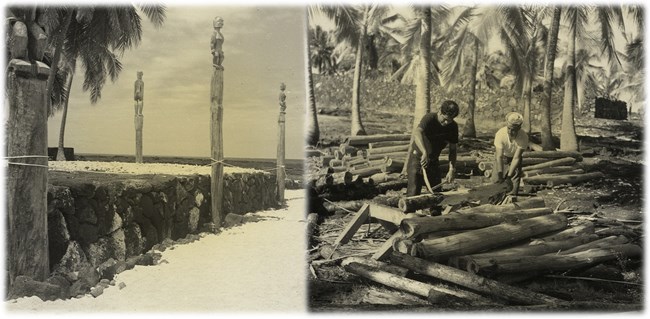

NPS Photos After the platform was restored, the National Park Service began work on reconstructing the surface features of the heiau including the thatched hale, wooden palisade, and kiʻi. While it is thought that the William Ellis depiction of the kiʻi surrounding Hale o Keawe is highly stylized, the layout and types of images could be discerned using the drawing. The park engaged scholars, artists and craftsmen who were knowledgeable of cultural traditions to guide and carry out the kiʻi reconstruction. Many of the carvers were maintenance workers in the park who brought their skills based on family knowledge to the park. Journey to Restoration: The Hale & Wooden Palisade

NPS Photos Next up on the journey to restoration was the thatched hale and wooden palisade. In addition to the Ellis depiction, the NPS studied sketches and notes done by Robert Dampier of H.M.S Blonde. These notes included details about the materials, that the interior wood of the hale was made of kauila wood, and that the palisade, or fence, consisted of coconut logs. First the posts and rafters of the hale were lashed, then dried ti leaf was placed as the wall covering thatch. Throughout the whole reconstruction process, visitors could come and observe the work in progress. The restoration process was key to the interpretive program at the time. Preserving for the FutureThe preservation of Hale o Keawe did not end with the restoration of the temple site. Preserving and caring for this sacred site is an ongoing joint-effort between the National Park Service and Native Hawaiian caretakers that have deep ties to the lands the park encompasses.

NPS Photo / Walsh

NPS Photo The National Park Service continues the process of preservation by continuing to repair and stabilize the restored temple structure. Since many of the restored structures are made of organic materials, they deteriorate over time and periodically need to be repaired or replaced. For example: since the restoration in the late 1960s, the kiʻi have been replaced twice, with the most recent replacement in 2004. Just as with the original restoration, local carvers (many of whom are family members of the original carvers) bring their skills and knowledge to continue the tradition.

NPS Photo While the National Park Service maintains the physical structure of the heiau, Native Hawaiians with deep connections to these lands continue to perpetuate ancestral traditions as caretakers and cultural practitioners, enabling the heiau to continue as a functioning religious site for Native Hawaiians. While the National Park Service and Native Hawaiian caretakers continue to work to preserve the Hale o Keawe heiau, the harmful effects of climate change pose a significant threat to future preservation. Sitting directly on the shoreline, Hale o Keawe will be affected by even minor fluctuations in sea level and stronger storm events could damage the temple site and surrounding area. Recent efforts for the future preservation of Hale o Keawe include an extensive, thorough, mapping project that will be used in both management planning and future preservation efforts. While it is unknown what the extent of the effects of climate change will have on Hale o Keawe and the rest of Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, the National Park Service is actively working to mitigate those future effects and continue to preserve the site for future generations. |

Last updated: September 30, 2020