|

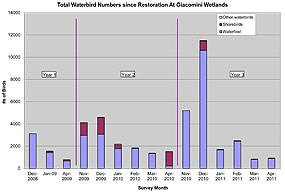

Published on November 28, 2011 What's Going on at Giacomini--in a Nutshell: Waterbird numbers continue to increase each year since restoration, particularly for dabbling ducks, with a record high number of more than 11,000 counted on one day in December 2011. However, shorebird numbers have been more variable. Numbers were low in the first winter after restoration, moderate in the second year and first half of the third year, and then declined sharply in the latter half of the third year. While the sharp drop in shorebird numbers in the third year occurred elsewhere in Tomales Bay, as well (Kelly and Condeso 2011), Giacomini is still evolving as potential shorebird habitat, with this evolution strongly dependent on invertebrate prey bases in marsh muds. In the early years, the restored wetland primarily attracted species that forage in the water column, ground, and in shallow sediments (J. Evens, ARA, pers. comm.), however, with arrival in fall 2011 of Marbled godwits, which forage more deeply in muds, this may be yet another confirmation of what we have observed through our benthic invertebrate and zooplankton monitoring results--numbers of benthic invertebrates in the restored wetlands are climbing dramatically, and species composition is shifting. See Untangling the Food Web: Changes in Prey Base Following Restoration. Scroll down or click on a link below to read more about Giacomini Wetlands: A Haven for Ducks: 2011 Update. Introduction Read Not Just for Ducks Anymore--the February 2010 update--for more in-depth information about waterfowl in the Giacomini Wetlands before restoration and during the first two years after restoration.

Introduction Perhaps, the most visible evidence of the early success of restoration efforts at Giacomini can be seen during the fall and winter, when thousands of birds are scattered across the shimmering expanse of blue. On a still day, the air reverberates with the sounds of flapping wings, splashing water, and the low hum/drone of chattering birds. The water that blankets the newly restored Giacomini Wetlands during the migratory season results in an explosion in waterbird numbers each fall and winter, and the numbers of these migratory converts continue to grow substantially each year. Numbers of waterbirds, particularly waterfowl, in Year Three greatly exceed that of Years Two and One, although shorebird numbers have varied dramatically since the levees were breached. Tidal wetlands in the greater San Francisco Bay area region provide especially valuable habitat for migrating and wintering waterbirds (Shuford et al. 1989; Goals Project 2000 in ARA 2010), and Tomales Bay is part of a network of Bay Area coastal estuaries that support waterbird populations of hemispheric importance (Kelly 2001). Fall is a period of avian movement and migration, the transition of species between nesting territories and wintering grounds (ARA 2009). Overall waterbird use tends to be low in the fall, but migratory flocks "stop-over" to forage for brief periods before moving on (ARA 2009). As one of the key coastal wetland stepping stones for migrating shorebirds along the Pacific coast, Tomales Bay provides a crucial stopover feeding habitat (Kelly and Condeso 2009). Individuals may stay only a few days to refuel before moving on, or they may stay longer (ibid). During fall migration, first year birds select wintering areas they will to return to in subsequent years (ibid). Little is known about this selection process, but most of them will probably make this choice by mid-November (ibid).

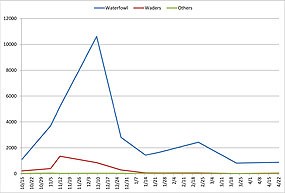

Before restoration, bird use of Giacomini was seasonally sporadic and rather limited. Pastures were used for roosting by Canada geese, Great blue herons, Great egrets, and mallards and nesting by grassland species such as Song and Savannah sparrows (ARA et al. 2002). The limited number of water features left in the dairy such as ditches and managed creeks also supported low numbers of Mallards, Gadwall, Lesser scaup, and Eared grebes (ARA et al. 2002). Occasionally, diving ducks such as Buffleheads used some of the old Duck Ponds created by the Giacominis for hunting (ARA et al. 2002). During the winter and spring, bird use would climb dramatically, with sustained flooding of lower elevation areas in the northeastern corner of the East Pasture, known as the Shallow Shorebird area. Dabbling ducks such as Gadwall, American wigeon, and Green-winged Teal stopped here, but the highest use probably came from shorebirds that would roost and forage here when tides were high in Tomales Bay (ARA et al. 2002). The most common shorebird visitors were Dunlin, Dowitcher, Greater yellowlegs, Common snipe, Willet and Killdeer (J. Kelly, ACR, pers. comm.). With restoration, waterfowl use of the Project Area was projected to remain similar to historic levels or increase slightly, while shorebird use was predicted to increase more dramatically (NPS 2007). As the marsh had subsided--or dropped in elevation very little since first being leveed in the 1940s--the former dairy ranch was expected to convert relatively quickly to a marsh very similar to the one directly north of Giacomini, near Inverness. This tidal marsh is predominantly marshplain with an intricate network of intertidal tidal creeks. This type of habitat would have great value for foraging shorebirds, but, without large ponds or open water areas, ducks would not find the restored marsh that attractive. Also, with conversion of pastures to marsh, numbers of grassland-associated species were expected to suffer the largest decline (NPS 2007). What actually happened astonished all.

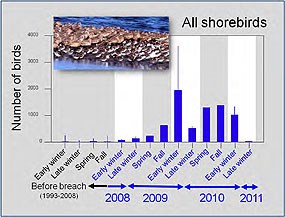

Year One Less than two months after the levees were breached, enormous flocks of waterfowl descended on the waters of the newly restored Giacomini Ranch. In December 2008, more than 3,295 waterbirds were counted during one morning survey (ARA 2011). Approximately 5,552 individuals and 44 different waterbird species were observed in 2008-2009, of which more than 90 percent were waterfowl species (ibid). The density of birds during this season averaged 8.1 per hectare (ibid). During that first winter, some of the species with the highest numbers were American wigeon (47%), Northern pintail (25%), Green-winged teal (6%), and Northern shoveler (3%). Other duck species included Gadwall, Mallard, Cinnamon teal, Bufflehead, and Ruddy duck. The potential value of the restored wetland for shorebirds, as well as waterfowl, must have seemed promising when a flock of dunlins flew into the wetlands on the day the final levee was breached. In early November 2008 surveys, shortly after breaching of levees, monitors from ACR observed some Short-billed and Long-billed dowitchers and scattered groups of Western and Least sandpipers in the newly restored marsh, Kelly said. Evens noted at least 1,000 Least and Western sandpipers around the edges of the flooded marsh in early November 2008 (Evens, pers. comm.). However, despite these early promising signs, numbers of shorebirds during the first winter was very low (ARA 2011, Kelly and Condeso 2011), accounting for less than 1% of all waterbirds observed by ARA during its surveys. Most of these species observed were Greater yellowlegs, Wilson's snipe, Killdeer, Least sandpiper, and Short-billed dowitcher (Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). Although shorebird use remained low during the first year after restoration relative to established feeding areas in Tomales Bay, shorebird abundance within the restoration area did seem to increase a bit in the late winter of the first year, though species composition remained similar (E. Condeso, pers. comm.). Later, during the peak migratory season for shorebirds in spring, shorebird numbers increased slightly yet again (ARA 2011, Kelly and Condeso 2011, although dabbling ducks still accounted for 84% of the waterbirds observed (ARA 2011). Though the distributions of shorebirds varied among counts, most of the shorebirds observed occurred in specific areas, including the East Giacomini Marsh (Shallow Shorebird Area in northern portion of East Pasture), the goby pond in the northern portion of the East Pasture, and the Triangle Marsh Area (Tomasini Triangle Marsh in central portion of East Pasture; Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). These ponded areas of the newly restored Giacomini Wetland provide habitat that seems suitable for a number of species (E. Condeso, pers. comm.). Year Two In Year Two, numbers of waterbirds climbed yet again, with peak numbers in December. During surveys, approximately 5,552 waterbirds were recorded using the site in 2008-2009, compared to 17,507 for the 2009-2010 season (ARA 2011). The number of species totaled 63 in 2009-2010 as compared to 44 species in 2008-2009 (ibid). Bird density increased to an average of 12.8 birds per hectare, up from 8.1 the year prior (ARA 2011). Some of the increases in abundance, density, and species richness may be due to the greater number of surveys conducted in Year Two, as official surveys doubled from three to six, however, the average number of birds per survey also climbed from 1,850.7 in 2008-2009 to 2,917.8 in 2009-2010, suggesting that increases were not just an aberration of a change in survey approach. During the migratory season, numbers increased from November to December, with some of the highest numbers were recorded in the December counts (6,262 on 12/12/09; ibid).

The most abundant species during this season was the dabbling duck, American wigeon, which also represented approximately 47 percent of the waterbirds observed in 2008-2009 (ARA 2011). Numbers of this species remained roughly equivalent during early surveys, peaking at 1,200 to 1,300 individuals, but declined to nearly half these numbers by January (ibid). Many of the other common waterfowl species such as Gadwalls, Mallards, Northern shovelers, Green-winged teal, and Northern pintail also showed peak abundances in December, with substantial declines in January (ibid). The only increases for waterfowl-like species occurred with Canada goose and American coot (ibid). In terms of shorebirds, wader abundance also climbed dramatically in Year Two, with the ACR August 2009 count totaling nearly three times as many birds as the highest winter 2008-2009 estimate (Kelly and Condeso 2009). This increase in numbers during the August survey was mostly due to a spike in the number of Least sandpipers observed (ibid). In addition to the species seen during the winter of 2008-2009, Western sandpipers, Dunlin, and Willets were also observed in spring and fall by ACR (ibid). Dunlins, which are the most abundant shorebird in Tomales Bay, did not visit the restored wetlands until Year Two (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Dowitchers were recorded in respectable numbers--66 for Short-billed and 5 for Long-billed-for the first time in fall 2009 (ibid).

Different types of species also started visiting the newly restored wetland. Of the 41 waterbird species observed by ARA in fall 2009, 20 species or approximately 38 percent of species were only observed during one census, with approximately 11 of the 20 species or 21 percent of the total represented by observation of only one individual (ARA 2009). Some of these individual sightings represented firsts for the Giacomini Wetlands since breaching of the levees in 2008, including American golden-plover, Solitary sandpiper, and Pectoral sandpiper (ARA 2009). Shorebird use of the restored wetland during the winter of 2009-2010 had climbed dramatically by January 2010 (ARA 2010). Abundance of shorebirds increased 25-fold from December and January 2008-2009 (87 individuals) to December and January 2009-2010 (2,221 individuals; ARA 2011). On the first two surveys, shorebirds accounted for 26 to 29 percent of all waterbirds detected, a substantial increase from 2008-2009, when shorebirds represented less than 1 percent of birds observed (ibid). In addition to the expected increase in small calidrine sandpipers (Least sandpipers and Dunlin), high numbers of Dowitchers and Yellowlegs were present (ibid). Some shorebirds occurred in very high numbers during December: Greater yellowlegs peaked at 79 individuals, and Dowitchers (probably Long-billed) climbed as high as 580 birds (ibid). Based on numbers from Kelly (2001), these numbers would appear to be exceptional for Tomales Bay. In addition, 500 Red-necked phalaropes that flocked in the northern portion of the East Pasture in "Goby pond" also represented a new high number of this region based on data from Shuford et al. (1989) and Kelly (2001; ARA 2011).

As with waterfowl, wader numbers started dropping in January and continued to decrease through April, with very few shorebirds present in spring 2010, although they represented an overwhelming majority (86.5%) of the birds present (ibid). Interestingly, Black-bellied plover numbers remained remarkably equivalent throughout the early winter surveys, suggesting that this species may have resided at Giacomini during that winter (ibid). Use of coastal estuaries is typically lower in wet years than dry years (ARA 2011). In addition, even should birds use coastal estuaries, mid-winter decreases in waterbirds associated with cumulative seasonal rainfall is common in Tomales Bay (Kelly and Tappen 1998, Kelly 2001) and other coastal estuaries (Colwell 1983, Shuford et al. 1989, Warnock et al. 1995 in ARA 2010, 2011). This decline may be associated with a shift to other now-flooded habitat such as pastures or shallow inland basins or with a seasonal shift in foraging patterns and prey availability (ARA 2010). In post-restoration monitoring, waterbird use of Giacomini Wetlands clearly declined by as much as approximately 63 to 73 percent in Years Two and Three, respectively, starting in late winter or January, typically when the heaviest rainfalls begin (ARA 2011).

Other species of note during the latter half of Year One and Year Two included Merlin, Long-billed curlew, Green heron, as well as non-waterbird species such as Bald eagles and Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus pealii) of the northern race (Kelly and Condeso 2009). Adults and immature Bald eagles, which were once extremely rare in west Marin, started visiting the site in spring 2009 and have remained occasional visitors to the wetlands, with at least four different individuals observed (ARA 2009).

Year Three During Year Three, numbers of waterbirds--particularly waterfowl--continued its seemingly incredible upward climb. Number of birds observed during all ARA surveys practically doubled from 17,507 in Year Two to 34,077 in Year Three (ARA 2011). As with previous years, abundance peaked in December, with a new high of 11,488 recorded on December 9, 2010 (ibid). Species richness also continued to rise from 63 in Year Two to 78 in Year Three (ibid). Average number of birds per survey climbed modestly from 2,917.8 in 2009-2010 to 3,407.7 in 2010-2011, which again suggests that some of the increase is related to survey frequency, which again increased from six in Year Two to 10 in Year Three, with assistance from ACR's shorebird surveys (ibid). Similar to Year One, waterbird composition was again dominated by waterfowl, representing 93.8% of all individuals observed (ibid). American wigeon also again represented the dominant species, accounting for 29.5% of all waterbirds (ibid). Peak densities of this species also jumped dramatically in Year Three from 7.5 and 5.7 birds per hectare in 2008-2009 and 2009-2010, respectively, to 18.1 in 2010-2011 (ibid). Similar dramatic increases in peak densities were also observed for Northern pintail--from 4.2 in Year Two to 11.5 in Year Three (ibid). The December 17, 2010, survey, in fact, marked high points in terms of numbers for several species, including American wigeon (4,127); Green-winged teal (1,408); Northern pintail (2,613); and American coot (1,224; ibid).

While peak pre-restoration densities are not readily available in the U.S. Geological Survey monitoring effort that was conducted prior to restoration to evaluate bird use of the unrestored dairy ranch, some conclusions about the effect of restoration can be made regarding mean densities of certain species (ARA 2011). Prior to restoration, dabblers such as American coot, American wigeon, and Northern pintail had the highest mean density per hectare of 6 per ha in the East Pasture (after American blackbirds; ARA 2011). Averaged for the entire Project Area, dabbler density dropped slightly to 4 birds/ha (ibid). In Year Three post-restoration, the same suite of six dabbling duck species--American wigeon, Gadwall, Green winged-teal, Northern pintail, Northern shoveler and Mallard--averaged 12.8 birds/hectare, an increase of 320% (ibid). The largest change occurred for Gadwall, which increased 21.4% relative to pre-restoration densities (ibid). Between Years Two and Three, abundances jumped for several dabbler species, including American wigeon, Green winged-teal, and Northern pintail, while those of others such as Gadwall and Northern shoveler and the one common diving duck, Bufflehead, remained relatively constant (ibid). Interestingly, the mean abundances of dabbling ducks at the newly restored wetlands in Years Two and Three greatly exceed any of the mean values reported by Kelly and Tappen in 1998 for all of Tomales Bay (ibid). Some of the new noteworthy additions to the restored wetlands during Year Three included Redhead, Eared grebe, Clark's grebe, Lesser yellowlegs, and Heerman's gull (ibid). Two species also "flew over" the site, but did not drop in--Surf scoter and Wandering tattler (ibid). A rare Yellow rail was also apparently detected in the newly restored West Pasture near Inverness Park during the Christmas bird count (K. Hansen, T. Easterla in ARA 2011). This species has been observed in the Undiked Marsh north of Giacomini in previous years, but never within the former dairy site (ibid).

The shorebird situation continues to puzzle. After a lackluster start in 2008-2009, waders appeared in 2009-2010 to have "found" the newly restored wetlands, with numbers increasing dramatically in Year Two. Numbers remained high even through fall and early winter of Year Three (Kelly and Condeso 2011; Figure 2 [60 KB PDF]), but in mid- and late- winter and spring, wader abundance plummeted relative to the previous year (ARA 2011, Kelly and Condeso 2011). For all ARA surveys combined in Year Three, waders represented only 5.7% of the waterbird community, compared to an average of 27.1% during Year Two (ARA 2011). Waders averaged 327.3 individuals/survey in Year Three, compared to 780.7 individuals/survey in Year Two (ARA 2011). On at least one count date in Year Three (11/12/10), shorebirds did account for 20.5% of all waterbirds observed (ARA 2011). This peak number illustrates one of the confounding variables of any biological or environmental monitoring efforts: surveys or sampling may not always catch peak abundance or concentrations. Most of ARA's survey effort was concentrated in mid- to late winter and spring, so, therefore, averages were skewed by the scarcity of waders during that period. However, this phenomenon was not relegated strictly to Giacomini. Reduced abundances of shorebirds occurred throughout Tomales Bay in late winter and spring of 2010-2011 (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Some of this may be due again to increased precipitation during those periods, as discussed earlier: The decline in numbers corresponds closely to the onset of rainy season (Figure 3 [118 KB PDF]).

Despite reduced shorebird numbers overall, some species continue to persist at the newly restored wetlands, including Greater yellowlegs, which had a peak abundance in Year Three of 82 individuals, roughly equivalent to Year Two (79 individuals; ARA 2011), although ACR surveys suggested a stronger decrease relative to Year Two (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Greater yellowlegs have always visited southern Tomales Bay in high numbers, leading some birders to consider it "magic" for this long-legged species (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Western sandpiper occurred in incredibly high numbers during Fall 2010 (mean of >800): juvenile fall migrant often determine wintering areas for future years (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Least sandpipers also returned in early winter of Year Three in roughly equivalent numbers to the prior year (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Wilson's snipe was one of the few species that remained relatively common in Year Three during both early winter and late winter surveys (Kelly and Condeso 2011). This species has always been attracted to the seasonally inundated or saturated grassy margins of the Project Area (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Conversely, numbers of species such as Dunlin (the most common shorebird in Tomales Bay), Black-bellied plovers, Dunlin, and Dowitchers fell dramatically during Year Three. Conclusions As with all biological species, increases and decreases from year-to-year cannot be evaluated without considering all the other potential factors that could affect these animals, such as climatic variation, impacts to non-wintering and other habitat, disease, and natural population dynamics or cycles. Bird use of the newly restored wetlands is dependent on a number of factors, including migratory birds finding the site and the site providing what the birds need to eat. The taxa observed so far have a wide range of dietary needs, from species that largely consume seeds and other plant matter to those such as Greater yellowlegs who eat fish and other aquatic prey. In general, the type of shorebirds that showed up during the early years were species that forage on the surface (e,g., Black-bellied plovers), shallow probers (e.g., Least sandpipers), and those that forage in the shallow water column (e.g., Greater yellowlegs; J. Evens, ARA, pers. comm.). Analysis of benthic invertebrate data suggests that numbers of benthic invertebrates within the restored wetlands are increasing, and this is perhaps borne out by the fact that, in fall 2011, Marbled godwits arrived for the first time in moderate numbers at the wetlands, signaling the presence of deeper substrate probers (J. Evens, ARA, pers. comm.). We are continuning to analyze changes in the zooplankton, benthic invertebrate, and fish communities in hopes of understanding how the prey base for many target organisms is changing with restoration. To evaluate how much of an effect the restoration itself might be having on higher bird numbers in southern Tomales Bay, Kelly and Condeso (2011) conducted an analysis to adjust shorebird abundances to take into account inter-annual variation observed for these species in other areas of Tomales Bay. What they found was that overall shorebird numbers in Tomales Bay closely match what might have been predicted even without restoration (Kelly and Condeso 2011). However, abundances of particular shorebird species did appear to be higher than would be predicted without restoration, including numbers of Least sandpiper, Western sandpiper, Dowitchers, Black-bellied plovers, and Greater yellowlegs (Kelly and Condeso 2011). Read the accompanying article, "The effects of large-scale restoration on regional shorebird use: just because you built it, does it necessarily mean that they will come?" for more detail on the results. In general, then, despite a slow start for shorebirds and some seasonal hiccups for all waterbirds, the restoration does appear to support higher numbers of birds after restoration (ARA 2011, Kelly and Condeso 2011). The future for bird use ultimately will depend on both extrinsic factors and intrinsic ones, including the trajectory taken by the marsh in its continued evolution, both from a physical and biological standpoint. -- Content for these pages was composed by Lorraine Parsons, Project Manager, Giacomini Wetland Restoration Project, Point Reyes National Seashore Special thanks to Galen Leed Photography for the wonderful photos! Read Audubon Canyon Ranch's report "Shorebird Use of the Giacomini Wetlands Restoration area: 2011 Update." to learn more about the shorebird changes! (903 KB PDF) Citations Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2002). Giacomini Wetland Restoration Site: special status animal species - reconnaissance and compliance, Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2009). Tomales Bay Wetland Restoration Site. Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2010). Tomales Bay Wetland Restoration Site Winter Avian Surveys, Years 1 & 2: Interim report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2011). Giacomini Marsh Wetland Restoration Avian Population Surveys: Winter 2008-2011. Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Colwell, M.A. 1983. Shorebird community patterns in seasonally dynamic estuary. Condor. 95:104-114. Goals Project. 2000. Baylands Ecosystem Species and Community Profiles: life histories and environmental requirements of key plants, fish, and wildlife. Prepared for the San Francisco Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project. P.R. Olofson, editor. San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board, Oakland, California. San Francisco Bay Estuary. Kelly, J.P. and S.L. Tappen. 1998. Distribution, abundance, and implications for conservation of winter waterbirds on Tomales Bay, California. Western Birds: 29:103-120. Kelly, J. and E. Condeso. 2009. Update on Shorebird Use of Newly Restored Wetlands. Prepared for Point Reyes National Seashore. Shuford, W.D., G.W. Page, J.G. Evens, and L.E. Stenzel. 1989. Seasonal abundance of waterbirds at Point Reyes: a California perspective. Western Birds. 20:137-265. Warnock, N. , G.W. Page, and L.E. Stenzel. 1995. Non-migratory movements of Dunlin on their California wintering grounds, Wilson Bulletin. 107:131-139. |

Last updated: June 27, 2024