As the cold of winter gradually gives way to the warmth of spring, the restored Giacomini Wetlands becomes home to a whole new group of animals, many of whom are only rare visitors to the Tomales Bay-Point Reyes area. With reintroduction of the tides to the former dairy ranch has come a slow conversion of pastureland to marsh. In the first spring after restoration, Atriplex triangularis seedlings--a brackish marsh plant species with triangular-shaped leaves--began to carpet many of the restored areas. In some of the more tidal areas, tiny pickleweed (Sarcocornia pacifica) seedlings also began to emerge, and patches of saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) expanded. In the second year of restoration, bright yellow flowers blanketed the new marshplains, with extensive colonization by another pioneer species, brass buttons (Cotula coronpifolia). The extent of this species began to die back starting in Year 4, and other marsh plant species took greater hold, including gum plant (Grindelia sp.), arrow-grass (Trigochlin maritima), salt marsh daisy (Jaumea carnosa), plantago (Plantago maritima), alkali grass ( To help us follow this transition from dairy ranch to coastal wetland, local wildlife biologists Jules Evens, Mary Anne Flett, Seth Bunnell, and Rich Stallcup of Avocet Research Associates have been conducting spring breeding bird surveys the past four years. Avocet also conducted baseline surveys of the Giacomini Ranch prior to restoration and has tracked bird use of the Giacomini Ranch and surrounding area for several decades.

Evens and his colleagues found that the Giacomini Wetlands continues to be home to many species that were common prior to and even during construction. White-tailed kites (Elanus leucurus) hover over the remnant grasslands, looking for rodents. Long-legged waders concentrate in impressive numbers along the channel bank-one March morning, more than 50 Great egrets (Casmerodius albus) and a dozen Snowy egrets (Egretta thula) and Great blue herons (Ardea herodias) were observed roosted along the main channel. As many as 130 White pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) congregated in open water areas in the northern portion of the East Pasture, up from 40 last year, said Louis Jaffe, a local resident who has been observing bird use in the wetlands. White pelicans are thought to be opportunistic fish-eaters, but, interestingly, a large flock foraging in the wetland panne shortly after restoration was consuming filamentous algae (J. Evens, pers. obs.) But there have been new visitors, too. Spring is the time for breeding, and many neotropical migrants or birds that may migrate from as far as South and Central America flock to this area to establish nests. During spring, Marin hosts as many as 150 species of breeding birds, and most of these occur on the coast (ARA et al. 2002). Tomales Bay cannot compete with San Francisco Bay in terms of sheer numbers, but Tomales Bay supports higher densities of many species (J. Kelly, ACR, pers. comm.) and accounts for a large proportion of many species' statewide population numbers. Tomales Bay is one of only three sites along the Pacific Flyway that support more than 100 Red knots (Calidris canutus) during spring migration (C. Hickey, PRBO, pers. comm.). Ten of the 17 Partners-in-Flight Riparian Focal Species breed in the Point Reyes region (C. Hickey, PRBO, pers. comm.). A large factor in the avian diversity found in Point Reyes comes from rare or extremely rare species, which account for nearly one-third of species observed (Evens 2008). Even prior to restoration, the Giacomini Ranch and surrounding area supported impressive breeding bird activity. The large freshwater marsh and adjacent riparian habitat in the West Pasture adjacent to Sir Francis Drake Boulevard was one of the breeding hotspots, supporting Saltmarsh common yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas var. sinuosa, former FSC, CSC), Virginia rail (Rallus limicola), Song sparrow (Melospiza melodia), Marsh wren (Cistothorus palustris), Brewer's Blackbird (Euphagus cyanocephalus), and other marsh-riparian associates (ARA et al. 2002). Two other areas that also attracted high number of breeding birds were the riparian-grassland habitats of Green Bridge County Park and the riparian-mesic coastal scrub habitats found on some portions of the Point Reyes Mesa bluff (ARA et al. 2002). Yellow warbler (Dendroica petechia brewsteri, CSC) has been observed breeding in the Green Bridge County park area and near Inverness Park and is a common fall migrant through riparian corridor (ARA et al. 2002). During baseline surveys, the Point Reyes Mesa bluff attracted a diverse array of the breeding birds observed in the area during spring, including species such as Swainson's thrush (Catharus ustulatus oedicus, CSC), Bewick's wren (Thryomanes bewickii, CSC), Wilson's warbler (Wilsonia pusilla), Warbling vireo (Vireo gilvus), and Allen's hummingbird (Selasphorous sasin, CSC; ARA et al. 2002). Saltmarsh common yellowthroat occurred in riparian habitat along the former Tomasini Creek channel (ARA et al. 2002).

Olema Marsh was once considered "one of the most diverse habitats for breeding, wintering, and migrating birds in the Point Reyes area" (Evens 2008). Between 1991 and 1994, total number of species ranged from 77 to 81 during the winter and from 44 to 49 species during the spring (Evens and Stallcup 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994). In 2004, this species richness trend reversed, with the number of species totaling 74 in spring and 65 in winter (Stallcup and Kelly 2004). Red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus), Marsh wren, and Song sparrow represented the most abundant species in autumn, winter, and spring, along with Saltmarsh common yellowthroat, which had at least 12 nesting territories during spring 2004 (Stallcup and Kelly 2004, 2005). California black rails (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus, ST) occasionally occurred in Olema Marsh, but Virginia rails were more common, along with Sora (Porzana carolina) sometimes in fall (Stallcup and Kelly 2004, 2005). It is no coincidence that the areas showing the highest breeding bird activity prior to restoration occurred on the perimeter of the Giacomini Ranch, where the juxtaposition between managed pasture and groundwater inflow from the Inverness Ridge and Point Reyes Mesa created a diverse mosaic of habitats. In contrast, the large expanse of monotypic habitats represented by 550 acres of managed pastures was "relatively depauperate in terms of supporting breeding birds in general and special status species in particular" (ARA et al. 2002). Savannah sparrows (Passerculus sandwichensis) were observed attempting to nest in some of the managed pastures, however, as had occurred for decades, many fields were mowed during the height of nesting, thus excluding perhaps a third of their population (ARA et al. 2002). During baseline surveys, the only avian species using managed pastures as its primary habitat was Grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum; former FSC, S2), but it arrived late and did not breed (ARA et al. 2002). Large flocks of migratory swallows sometimes foraged low over pastures and marshes, especially early and late in the day (ARA et al. 2002).

In 2008, then, breeding in the then dormant pastures reached a new zenith with discontinuation of agricultural management. (Mowing for construction purposes was only conducted after breeding had stopped, and chicks had fledged). Red-winged blackbirds, Song sparrows, and Savannah sparrows took advantage of the lush green fields, redoubling their nesting efforts and producing two broods in a single season, Evens noted. A pair of Northern harriers or Marsh hawks (Circus cyaneus) also nested in some of the fallow fields. White-tailed kites hunted the pastures by day, while Barn owls (Tyto alba) hunted them by night, feasting on the booming vole population, which also increased in response to the decrease in mowing and an increase in seed production by grasses. With the decrease in disturbance that had been caused by mowing and cattle, numbers of Wilson's snipe (Gallinago delicata) were found foraging and roosting in the moist pasture in fall, winter and spring. (Snipe do not nest locally.)

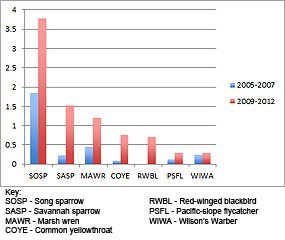

In the three years since restoration, breeding bird activity has increased relative to both ranching days and the period immediately before construction. Figure 1 (85 KB PDF) shows density changes between pre-restoration (2005-2007) and post-restoration (2009-2012): Density of key wetland-dependent passerines has increased universally after restoration (ARA 2011a). Ninety-three (93) avian species have been found during point counts in spring surveys (ARA 2012). Slightly less than two-thirds of these species (65.3%) are considered local breeders--that is, they either nest on-site (e.g., Mallard, Common yellowthroat, Song sparrow) or they forage on-site and nest nearby (e.g., Great blue-heron, Red-tailed hawk; 2012). Overall, species richness and the total number of observations was actually highest in Year 2 or (2010) than in Year 1, 3, or 4 (ARA 2012). Approximately 501 birds were sighted in 2009, compared to 940 in 2010, 729 in 2011, and 890 in 2012 (all detections; ibid). The newly restored wetlands supported 65 breeding bird species in 2009, 74 in 2010, and 48 in 2011 (all detections; ARA 2011a). The seeming decline in both numbers and species in 2011 may be an artifact of field effort timing and weather (ibid). Surveys were conducted in late April and mid-May during Years 1 and 2 and mid-May to early June in Year 3 (ibid). Compounding the potential effect of the difference in timing was the unusual amount of late rains that occurred in Year 3, which may have suppressed or disrupted breeding activity (ibid). While Year 3 had lower numbers and species richness than preceding years, numbers of specific wetland-dependent focal species have generally continued to increase in Year 3 (ARA 2011a) and again in Year 4 (ARA 2012). These species include Song sparrow, Savannah sparrow, Marsh wren, Common yellowthroat, Red-winged blackbird, Pacific-slope flycatcher, and Wilson's warbler (ARA 2012). Wilson's Warbler, which showed a decrease in territories per point in 2011, increased in abundance again in 2012, more than doubling in number since the pre-restoration period (ARA 2012). Two species with relatively strict habitat requirements--"Salt-marsh" common yellowthroat and "Bryant's" savannah sparrow--showed showed some of the highest increases since restoration. Density of common yellowthroat climbed from 0.09 territories per point between 2005 and 2007 to 1.10 territories per point in 2012 and 0.73 territories per point between 2009 and 2012 (ARA 2012). Density of Savannah sparrow also jumped sharply after restoration from 0.23 territories per point before levee breaching to 1.44 territories per point in 2012, a slight drop from the overall average of 1.66 territories per point for all years after restoration (ibid). Both of these subspecies are considered "California Bird Species of Special Concern" by the California Department of Fish and Game (Shuford and Gardali 2008 in ARA 2011a). In general, Song sparrows were by far the most common breeding bird species during the spring in the newly restored wetlands, with densities reaching an average of 3.71 territories per count between 2009 and 2011 (ARA 2012). Savannah sparrows were the second most common (1.66 terr/pt), followed by Marsh wren (1.13 terr/pt), Red-winged blackbird (0.92 terr/pt), and Common yellowthroat (0.73 terr./pt; ibid). Salt marsh common yellowthroat and other wetland-dependent species have taken advantage of the newly establishing riparian thickets that were suppressed in years past by grazing. Species that had nested only along the edges of the wetland expanded their territories into the lowlands. With this increase in available habitat, larger numbers of songbirds are nesting and have improved reproductive success. The vegetation along lower Fish Hatchery Creek has developed into a lush fresh to brackish transitional wetland lined with marsh monkey flower, watercress, reeds and rushes growing waist high. In Year 1, Marsh wrens, Song sparrows, and Virginia rails were particularly abundant here, and a rare California black rail was calling on territory here in late April.

Perhaps, some of the most compelling visitors to the newly restored coastal wetland since restoration have been the Bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and the California black rails. Bald eagles showed up only after restoration was completed. They are not very common in the Tomales Bay watershed, although sightings have increased in recent years. The adult Bald eagles tend to show up when the bulk of the ducks arrive--late-October into January (J. Evens, ARA, pers. comm.). Immatures (1-3 year olds) pass over irregularly in the fall, but they are not common (ibid). California black rail is a state-threatened species that has all but disappeared from many of its historic habitats and has been barely clinging on to its formerly extensive habitats in Tomales Bay. Prior to restoration, almost all of the rail sightings in Tomales Bay were in the undiked marsh directly north of the Giacomini Ranch. In Year 1, three California Black Rails were heard calling from the newly created marsh in April and May, however, focused surveys were not conducted, so estimated numbers of these species were not able to be determined (ARA 2009). In Year 3, focused rail surveys were conducted, and rails were detected at three of the 17 census points, with all of the detections in the northern portion of the West Pasture adjacent to the Freshwater Marsh (ARA 2011b). Although focused surveys were not conducted in Year 4, rails were still estimated to have established a minimum of three territories in the West Pasture during this past year (ARA 2012). Rails also still occur in the undiked marsh (ARA 2011b). The amount of potential rail habitat in the restored Giacomini Wetlands appears greater than is currently utilized, so rail numbers could increase in the future (ibid).

Birds are not the only common visitors to the newly restored Giacomini Wetlands.

"Although we knew that the restoration would benefit the wetland community, no one anticipated how quickly these creatures would find their new habitat or how quickly they would exploit the diversity of new habitats created," noted Evens. -- Content for this page was composed by Lorraine Parsons, Project Manager, Giacomini Wetland Restoration Project, Point Reyes National Seashore Citations: Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2002). Giacomini Wetland Restoration Site: special status animal species - reconnaissance and compliance, Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2009). Giacomini Wetland Restoration Site. Nesting Season Avian Surveys. Spring 2009. Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2011a). Giacomini Wetland Restoration Site. Nesting Season Avian Surveys: 2009-2011. Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2011b). Giacomini Marsh Wetland Restoration Site. California black rail (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus) 2011 Nesting Season Surveys. Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2012). Giacomini Wetland Restoration Site. Nesting Season Avian Surveys: 2009-2012. Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Evens, J. 2008. Natural History of the Point Reyes Peninsula. University of California Press, Berkeley. 366pp. Evens, J. G. and R. W. Stallcup (1991). "Coastal Riparian Marsh." Breeding Bird Census 62(1): 75-76. Evens, J. G. and R. W. Stallcup (1992). "Coastal Riparian Marsh." Breeding Bird Census 63(1): 95-96. Evens, J. G. and R. W. Stallcup (1993). "Coastal Riparian Marsh." Breeding Bird Census 64(1): 91-92. Evens, J. G. and R. W. Stallcup (1994). "Coastal Riparian Marsh." Breeding Bird Census 65(2): 105-106. Shuford, W.D. and T. Gardali, eds. 2008. California Bird species of Special Concern: A ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California. Studies of Western Birds 1. Western Field Ornithologists, Camarillo, California and California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento. Stallcup, R. W. and J. P. Kelly (2004). Point-Count Surveys of Bird Use in Olema Marsh: Spring and Autumn 2004, Prepared for Point Reyes National Seashore by PRBO Conservation Science and Cypress Grove Research Center. Stallcup, R. W. and J. P. Kelly (2005). Point-Count Surveys of Bird Use in Olema Marsh: Winter 2005, Prepared for Point Reyes National Seashore by PRBO Conservation Science and Cypress Grove Research Center. |

Last updated: October 14, 2022