|

Published on February 13, 2010

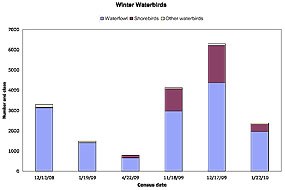

The broad expanse of water that covers the newly restored Giacomini Wetlands during fall and winter months results in an explosion in waterbird numbers. Indeed, numbers of shorebirds and even waterfowl were higher in the fall and winter of 2009 than in 2008 and represent a noticeable increase in waterbird numbers prior to restoration.

Before 2008: Conditions Prior to Restoration To determine just how much birds used the Dairy Ranch prior to restoration, the Park Service hired Jules Evens of Avocet Research Associates (ARA) to document avian numbers and species diversity and to determine which existing habitats were most important. Prior to restoration, avian use of the pastures was seasonally variable. The northern portion of the East Pasture frequently hosted roosting Canada geese (Branta canadensis), Great blue herons (Ardea herodias), Great egrets (Ardea alba), and, occasionally, waterfowl species such as Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos; ARA et al. 2002). The ditches in the East Pasture supported a low diversity of species that include occasional use by Mallards, Gadwall (Anas strepera), Lesser scaup (Aythya affinis), Eared grebe (Podiceps nigricollis), Black phoebe (Sayornis nigricans), and even Belted kingfisher (Ceryle alcyon; ARA et al. 2002). Buffleheads (Bucephala albeola) regularly used some of the old Duck Ponds created by the Giacominis (ARA et al. 2002).

The greatest waterfowl and shorebird use in the pastures prior to restoration occurred in what is known as the Shallow Shorebird area in the northeast corner of the East Pasture, a unique habitat within the Project Area. This Muted Tidal Brackish Marsh-Flat/Panne typically flooded from December through April with surface runoff, precipitation, and tidal waters that flow into the East Pasture from a culvert in the levee of the Tomasini Creek berm, creating brackish water conditions. Many waterfowl species, especially dabbling ducks such as Gadwall, Wigeon, and Teal, have been historically attracted to this area in the winter (ARA et al. 2002). Shorebirds also gathered here in rather high numbers to roost and forage when adjacent tidal flats are inundated at high tide (ARA et al. 2002). Some of the most common shorebird species included Dunlin (Calidris alpina), Dowitcher species (Limnodromus sp.), Greater yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca), Common snipe (Gallinago gallinago), Willet (Tringa semipalmata), and Killdeer (J. Kelly, ACR, pers. comm.).

In addition to these more persistent habitats, waterfowl also often congregated in large numbers prior to restoration in the southern portion of the West Pasture in seasonally flooded-ponded Meadows and Pastures that receive significant freshwater inflow after rain events from groundwater and small drainages flowing off the Inverness Ridge. Year One (2008-2009: Ducks, Ducks, and More Ducks With restoration, waterfowl use of the Project Area was projected to remain similar to historic levels or increase slightly, while shorebird use was predicted to increase. However, in the first few months after breaching in October 2008, these trends have were seemingly reversed, with duck numbers greatly exceeding those of shorebirds, although, based on anecdotal information, shorebirds were occasionally present in high numbers (Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data; ARA, unpub. data).

Numerous visitors and staff have commented on the enormous flocks of waterfowl that congregated on the waters of the newly restored Giacomini Ranch. During the mid-December 2008 extreme high tide series, where tides reached levels of 7.1 feet MLLW, Evens and colleagues counted more than 3,400 waterbirds during one morning survey (ARA, unpub. data). Approximately 43 different waterbird species were observed in 2008-2009 (ARA 2010). More than 90 percent of the waterbirds observed were dabbling duck species (ibid). Some of the species with the highest numbers were American wigeon (Anas Americana) (47%), Northern pintail (Anas acuta) (25%), Green-winged teal (Anas crecca; 6%), and Northern shoveler (Anas clypeata; 3%). Other duck species included Gadwall, Mallard, Cinnamon teal (Anas cyanoptera), Bufflehead, and Ruddy duck (Oxyura jamaicensis).

Shorebird numbers might have been expected to be higher than waterfowl based on predicted water levels after levee removal. However, shorebird numbers in 2008-2009 were relatively low, according to John Kelly, wildlife biologist at Audubon Canyon Ranch (ACR), who has been conducting shorebird surveys with his staff and volunteers in the Giacomini Ranch and Tomales Bay. In early November 2008 surveys, shortly after breaching of levees, monitors from ACR observed some Short-billed and Long-billed dowitchers (Limnodromus griseus and L. scolopaceus) and scattered groups of Western sandpipers (Calidris mauri) and Least sandpipers (Calidris minutilla) in the newly restored marsh, Kelly said. Evens noted at least 1,000 Least and Western sandpipers around the edges of the flooded marsh in early November 2008 (Evens, pers. comm.). Phalaropes (Phalaropus lobatus) were very common in the Project Area prior to breaching of the levees: Phalaropes are transients and are typically present in large numbers during fall migration, Evens said.

Kelly noted that many of the shorebirds observed in the area before mid-November may be fall migrants that do not winter locally in Tomales Bay. After mid-November, numbers and species observed should reflect the value of the wetland to locally wintering individuals, Kelly said. During a survey of the Giacomini Wetlands on November 17, 2008, ACR monitors observed 98 shorebirds (Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). Most of these birds were Greater yellowlegs (21), Wilson's snipe (Gallinago delicata) (18), Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) (30), Least sandpiper (26), and Short-billed dowitcher (3) (Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). On December 3, 2008, even fewer shorebirds were observed: 15 in total - 5 Killdeer, 2 Greater yellowlegs, 5 Wilson's snipe, and 3 Least sandpipers (Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). These numbers represent shorebird use at moderate tide levels (approximately 2.5-4.0 feet above MLLW).

During the survey by Evens and colleagues on December 13, 2008, shorebird numbers were slightly higher, with 30 Greater yellowlegs observed, as well as more than 100 gulls of different species. Audubon Canyon Ranch (ACR) conducted additional shorebird counts during the late winter season. During censuses, ACR observers counted a grand total of 538 shorebirds in the new Giacomini Wetlands, according to Emiko Condeso of ACR. (Table 1).

Although shorebird use remained low relative to established feeding areas in Tomales Bay, shorebird abundance within the restoration area did seem to increase a bit compared to the first half of the winter monitoring period, though species composition remained similar, Condeso noted. Species known to be associated with ponds and flooded pastures continued to have a strong presence, such as Great blue herons, Great egrets, Snowy egrets, Greater yellowlegs, Killdeer, and Wilson's snipe (Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). Least sandpipers, which were observed in low numbers during ACR's early winter counts (Nov-Dec) turned up in higher numbers during late winter counts (Jan-Feb; Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). While Dowitcher numbers remained low during formal surveys, Condeso noted that flocks of Dowitchers were observed within the restoration area on non-survey days. Though the distributions of shorebirds varied among counts, most of the shorebirds observed occurred in specific areas, including the East Giacomini Marsh (Shallow Shorebird Area in northern portion of East Pasture), the goby pond in the northern portion of the East Pasture, and the Triangle Marsh Area (Tomasini Triangle Marsh in central portion of East Pasture; Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data). These ponded areas of the newly restored Giacomini Wetland provide habitat that seems suitable for a number of species, Condeso said.

In addition to water level and fluctuations, other less obvious factors may have affected shorebird use in 2008-2009, including changes in the availability of prey and the traditional use of other areas in Tomales Bay by resident wintering shorebirds, Kelly noted. Ultimately, Kelly felt that the Giacomini Wetlands could provide an important feeding area for shorebird flocks during high tides and periods of heavy stormwater run-off when tidal flats in Tomales Bay become inundated. In addition, Evens noted that the type of shorebirds that use ponded areas rather than mudflats are typically more abundant in fall and spring rather than winter, passing through during migration. These fall and spring migrants-Yellowlegs, Sandpipers, Dowitchers-will likely congregate in high numbers in areas with muted tidal action or where upland runoff creates shallow ponds (e.g. Tomasini Triangle marsh). The value of the Giacomini Wetlands for these shorebirds may take more develop to become apparent as breaching of the levees occurred after most of the fall migration in 2008 had already occurred, and shorebirds were already beginning to settle into wintering areas, Condeso pointed out. Year Two: What a Difference a Year Makes Fall Shorebirds Fall is a period of avian movement and migration, the transition of species between nesting territories and wintering grounds (ARA 2009). Overall waterbird use tends to be low in the fall, but migratory flocks "stop-over" to forage for brief periods before moving on (ARA 2009). As one of the key coastal wetland stepping stones for migrating shorebirds along the Pacific coast, Tomales Bay provides a crucial stopover feeding habitat (Kelly and Condeso 2009). Individuals may stay only a few days to refuel before moving on, or they may stay longer (ibid). During fall migration, first year birds select wintering areas they will to return to in subsequent years (ibid). Little is known about this selection process, but most of them will probably make this choice by mid-November (ibid). The Giacomini Wetlands were first flooded by tides at the end of October 2008, so the gradual process of wetland habitat restoration probably had little effect on recruitment choices of shorebirds in 2008 (ibid). Not surprisingly, both ACR and ARA found relatively low use of the area by shorebirds in the winter months following the breach (Kelly and Condeso, unpub. data; ARA, unpub. data).

However, during the fall 2009 migration period, both ACR and ARA observed increased overall shorebird abundance, with the ACR August 2009 count totaling nearly three times as many birds as our highest winter 2008-2009 estimate (Kelly and Condeso 2009; Table 2). This increase in numbers during the ACR survey was mostly due to a spike in the number of Least sandpipers observed (ibid). In addition to the species seen during the winter of 2008-2009, Western sandpipers, Dunlin, and Willets were also observed in spring and fall by ACR (ibid). Dowitchers were recorded in respectable numbers-66 for Short-billed and 5 for Long-billed-for the first time in fall 2009 (ibid). A group of Red-necked phalaropes (53 birds) was again observed in the wetlands in early fall 2009: they had been common visitors to the site during the construction phase in 2008 (ARA, unpub. data.; NPS staff, pers. obs.). During ARA surveys, approximately 41 waterbird and 11 raptor species were detected during four survey periods from August to October 2009 (ARA 2009). Of waterbirds detected, 20 species or approximately 38 percent of species detected were only observed during one census, with approximately 11 of the 20 species or 21 percent of the total represented by observation of only one individual (ARA 2009). Some of these individual sightings represented firsts for the Giacomini Wetlands since breaching of the levees in 2008, including American golden-plover (Pluvialis dominica), Solitary sandpiper (Tringa solitaria), and Pectoral sandpiper (Calidris melanotis). Some of the earliest visitors to the site included Western sandpiper and Red-necked phalaropes (ARA 2009). Greater yellow-legs (Tringa melanoleuca), which prefer shallow, standing water, peaked in abundance in late fall 2009 counts, with numbers appearing to increase as fall transitioned to winter (ARA 2009). Some regular winter visitors such as American wigeon, which was extremely common in the newly restored wetlands in winter 2008-2009, were present during some sampling periods in the fall, but absent in others: some species tend to be transitory visitors in the fall, but regular in the winter. Other species of note included Merlin (Falco columbarius), Long-billed curlew (Numenius americanus), and Green heron (Butorides striatus).

Some non-waterbird species observed included Bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus pealii) of the northern race (ACR 2009). Adults and immature Bald eagles, which were once extremely rare in west Marin, started visiting the site in spring 2009 and have remained common visitors to the wetlands, with at least four different individuals observed (ARA 2009). Though the distributions of shorebirds varied among counts, shorebird use of the restoration area continued to concentrate in the areas ACR refers to as the East Giacomini Marsh (Shallow Shorebird Area) and the Triangle Marsh Area (Tomasini Triangle Marsh; Kelly and Condeso 2009). These ponded areas of the newly restored Giacomini Wetland provide suitable habitat for a number of species. To date, not many shorebirds have been observed in the densely vegetated west side of the restoration area (West Pasture), however, the importance of this area for shorebirds could increase during wet years, especially during periods of high run-off coupled with high tides (Kelly and Condeso 2009). The increase in species diversity and numbers of individuals observed in both ARA and ACR surveys suggest that shorebirds are now "finding" the Giacomini Wetlands (ARA 2009). Although occurrence of species was sporadic during fall counts, the increase in numbers and species presages the potential for higher use of the restored wetlands in winter 2009-2010 (ibid). Both ARA and ACR point out that there is not enough data currently to determine population trends, but shorebird use of the Giacomini Wetlands does appear to be on the rise, at least in the short-term. Winter 2009-2010: Interim Results Tidal wetlands in the greater San Francisco Bay area region provide especially valuable habitat for migrating and wintering waterbirds (Shuford et al. 1989; Goals Project 2000 in ARA 2010), and Tomales Bay is part of a network of Bay Area coastal estuaries that support waterbird populations of hemispheric importance (Kelly 2001).

Numbers of waterbirds using the newly restored Giacomini Wetlands was high in 2008–2009 and even higher in 2009–2010 (ARA 2010; Figure 1 - 51 KB PDF). During surveys, approximately 5,546 waterbirds were recorded using the site in 2008–2009, compared to 12,778 birds midway through the 2009–2010 season (ibid). The number of species totaled 53 midway through winter 2009–2010 as compared to 43 species for all of 2008–2009 (ibid). Numbers increased from November to December, with some of the highest numbers were recorded in the December counts (ibid). The most abundant species during this season was the dabbling duck, American wigeon, which was also represented approximately 47 percent of the waterbirds observed in 2008–2009 (ibid).

Many of the other waterfowl species such as Gadwalls, Mallards, Northern shovelers (Anas clypeata), Green-winged teal, and Northern pintail showed peak abundances in December, with substantial declines in January (ARA 2010). The only increases for waterfowl-like species occurred with Canada goose (Branta canadensis) and American coot (Fulica americana; ibid). Mid-winter decreases in waterbirds associated with cumulative seasonal rainfall has been reported for Tomales Bay (Kelly 2001) and other coastal estuaries (Colwell 1983 in ARA 2010). This decline may be associated with a shift to other now-flooded habitat such as pastures or shallow inland basins or with a seasonal shift in foraging patterns and prey availability (ARA 2010). Shorebird use of the restored wetland during the winter of 2009-2010 had climbed dramatically by January 2010 (ARA 2010). On the first two surveys, shorebirds accounted for 26 to 29 percent of all waterbirds detected, a substantial increase from 2008-2009, when shorebirds represented less than 1 percent of birds observed (ibid). In addition to the expected increase in small calidrine sandpipers (Least sandpipers and Dunlin), high numbers of Dowitchers and Yellowlegs were present (ibid). Some shorebirds occurred in very high numbers during December: Greater yellowlegs peaked at 79 individuals, and Dowitchers (probably Long-billed) climbed as high as 580 birds (ibid). Based on numbers from Kelly (2001), these numbers would appear to be exceptional for Tomales Bay, suggesting that the restored wetland has increased the availability of suitable habitat for these species or effectively concentrated these species in one area (ibid). As with waterfowl, shorebird numbers fell off in January, as did its relative numbers, dropping down to approximately 15 percent of all waterbirds observed (ibid). Interestingly, Black-bellied plover (Pluvialis squatarola) numbers remained remarkably equivalent throughout the early winter surveys, suggesting that this represents a resident winter flock (ibid). ACR conducts simultaneous shorebird counts throughout Tomales Bay and would like to expand its monitoring at some point to monitor shorebird use at different tide levels. Experienced "birders" with the requisite skills interested in contributing to these counts should contact Emiko Condeso of the Cypress Grove Research Center of ACR at 415-663-8203 or email) for more information. Special thanks to Galen Leed Photography for the wonderful photos! Citations: Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2002). Giacomini Wetland Restoration Site: special status animal species - reconnaissance and compliance, Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2009). Tomales Bay Wetland Restoration Site. Final report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Avocet Research Associates (ARA; 2010). Tomales Bay Wetland Restoration Site Winter Avian Surveys, Years 1 & 2: Interim report to Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service. Colwell, M.A. 1983. Shorebird community patterns in seasonally dynamic estuary. Condor. 95:104–114. Goals Project. 2000. Baylands Ecosystem Species and Community Profiles: life histories and environmental requirements of key plants, fish, and wildlife. Prepared for the San Francisco Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project. P.R. Olofson, editor. San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board, Oakland, California. San Francisco Bay Estuary. Kelly, J.P. 2001. Distribution and abundance of winter shorebirds on Tomales Bay, California: Implications for conservation. Western Birds. 32(3):145–166. Kelly, J. and E. Condeso. 2009. Update on Shorebird Use of Newly Restored Wetlands. Prepared for Point Reyes National Seashore. Shuford, W.D., G.W. Page, J.G. Evens, and L.E. Stenzel. 1989. Seasonal abundance of waterbirds at Point Reyes: a California perspective. Western Birds. 20:137–265. -- Content for this page was composed by Lorraine Parsons, Project Manager, Giacomini Wetland Restoration Project, Point Reyes National Seashore | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Last updated: October 14, 2022