America's LongfellowAn essay by Matthew Gartner

IntroductionLongfellow is one of the monumental cultural figures of nineteenth-century America, the nation's preeminent poet in his era, whose verse is notable for its lyric beauty, its gentle moralizing, and its immense popularity. A New Englander through and through who traveled widely in Europe and knew a dozen languages, a Harvard professor, and the country's first professional poet, Longfellow heralded a new spirit in American letters. His fame grew until it took on a life of its own, and he was revered and beloved to a degree few poets have been before or since. When Longfellow began his literary career in the 1820s, poetry often seemed a needless luxury to the practical-minded citizens of the still-young American republic. Along with such other genteel poets as William Cullen Bryant, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and James Russell Lowell, Longfellow played an important role not just in helping make poetry respectable, but more broadly in refining and cultivating middle-class readers. In the gentle hands of Longfellow, readers could be introduced to the finer things in life – domestic sympathies, noble aspirations, spiritual consolations, the glories of high culture – without ever being made to feel intimidated or inadequate. A peculiarly American mixture, Longfellow was both a patrician and a populist, an artist of elite social background whose writing reverberated with the masses. One reader, a Mrs. Julia Willard, captured the experience of many when she wrote Longfellow, late in his life, "Your beautiful poems have been a rest, a blessing, a sweet, pure, calming benediction to me ever since I learned to read them in my childhood years." Over and above his poetry's success and influence, Longfellow became himself a living icon who filled a central niche on the American scene. Americans read his poetry by firesides, in schools, at public occasions; they heard musical renditions sung in parlors and concert-halls; their children celebrated his birthday in school and memorized and recited his poems. Because of his singularly large reputation, a result not only of the place he carved out for himself but also of sustained promotional efforts on the part of his publishers and defenders, Longfellow became a looming presence, an important symbol for his fellow Americans, representing a set of values and meanings that changed as the country did through the century. Although his reputation declined precipitously after his death in 1882, a Longfellow revival of kinds may now be under way as it becomes possible to see afresh his considerable poetic achievements and historical significance.

PoetryThe nature of Longfellow's poetic genius is elusive, hard to pin down, though it may help to recall that first and foremost he was a public poet. That is to say, he always wrote with his audience in mind, paternally consoling and uplifting them in lyrics, ballads, odes, sonnets, verse dramas, and the long narrative poems whose characters became hallmarks of American culture: Evangeline, Hiawatha, the Puritan maiden Priscilla, the midnight-riding Paul Revere. The essential note of his poetry, its sweet and settling mildness, its serene reassurance, was perfectly modulated to appeal to the reading public. This was socially responsible poetry, poetry with purpose, whose often explicit message urged such virtues as patience, resignation, and hard work. Given these themes, it seems fitting that as a poetical craftsman he was not boldly original or radically experimental, as were his contemporaries Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. Rather, Longfellow fashioned his poems out of tried-and-true materials: accessible ideas and language, pleasing stories and rhyme, familiar feelings and form. In a well-known lyric from 1844, "The Day Is Done," Longfellow voiced what may be thought of as his poetic intentions; in this poem about poetry – a favorite subject of his – he celebrates poems that "have power to quiet/The restless pulse of care,/And come like the benediction/That follows after prayer." In these direct, clear, and mellifluous lines, one can see how Longfellow is content to speak simply and softly. Indeed, he adopted as a personal motto a Latin phrase, Non clamor sed amor, borrowed from an anonymous poem he himself translated: "Not loudness but love." The great American author Nathaniel Hawthorne, a friend and college classmate of Longfellow's, praised just this understated quality: "No one but you would have dared to write so quiet a book," he wrote in an 1850 letter to Longfellow. The remark highlights the way Longfellow's literary strength lies not in breaking rules, but in following them, not in transgressing, but in staying within bounds. Longfellow always felt himself dutifully answerable to his readers – he was a poet, quite literally, with a known address – and this sense of public obligation shaped his poetry and his life in fundamental ways. Though Longfellow was hardly a poet of the startlingly new, he undeniably did break new ground in American poetry, and this was in large part due to the way that, in him, expressive poetic genius met and battled with the stolid forces of New England repression. The result was a strange kind of poetry, shuttling between America and Europe, between Puritan reticence and Romantic feeling, between pious instruction and aesthetic pleasure, between aristocratic ideals and egalitarian principle. Longfellow held these oppositions together by keeping his poetry's energies oriented toward his readers. In other words, the popular success of this often self-contradictory poet may have been possible only because the United States in the mid-to-late nineteenth century was such a conflicted place. Longfellow managed to speak to the conflicts and at the same time to seem a safe haven, an anchor in the storm.

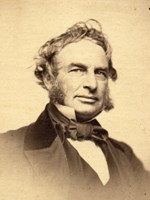

Life and FameLongfellow's benign poetic temperament owes much to his full and fortunate life. Born in Portland in 1807, when that bustling port city was still part of Massachusetts, Longfellow came from an old, established family of lawyers, judges, and generals. Enrolled at Bowdoin College by the age of fourteen, during his senior year Longfellow published no less than sixteen poems in a leading literary journal, the United States Literary Gazette. Upon his graduation the Bowdoin trustees (his father conveniently happened to be one!) appointed him to a provisional professorship, sending him off to Europe for three years of preparatory study. He stayed for four, returning to Maine to start his teaching career in 1829. His next years were productive ones, and his ambition, hard work, and social connections paid off when in 1835, at the age of 28, he was offered the most prestigious position in his field (what we would now call "Comparative Literature") that the country had to offer: the Smith Professorship of Modern Languages at Harvard. Granted a year to travel in Europe before taking up his duties, Longfellow was in Rotterdam with his wife Mary Potter Longfellow when she suffered a miscarriage and died from its complications. Distraught, he continued to drift through Europe for the rest of the year. Installed at last in Cambridge in the fall of 1836, the major, most productive and important phase of his life was about to begin. This phase was marked by his return, after an almost ten year interruption, to writing poetry. His breakthrough poem, "A Psalm of Life," published in the Knickerbocker magazine out of New York and reprinted in newspapers across the country, stirred a generation of readers with its heady exhortations:

With the publication in 1839 of his first collection of poems, Voices of the Night, and that same year of his novel Hyperion, Longfellow established himself as one of America's leading authors. Still in his early thirties, a well-dressed, cosmopolitan figure in small-town Cambridge, Longfellow formed close friendships with other young men of patrician backgrounds and promising futures, and turned his attention to the daughter of a prosperous Boston industrialist, Fanny Appleton, whom he had met for the first time in Switzerland in the summer of 1836. Unusually determined as a suitor, Longfellow waited seven long years before she relented, and the two were married in 1843. As a wedding present her father, Nathan Appleton, bought the couple the historic Craigie House on Brattle Street, a short walk from Harvard Square (Longfellow had been renting rooms there since 1837, and the house came on the market at a fortuitous moment). Henry and Fanny raised five children in Craigie House, and lived among friends and family in great comfort, happiness, and privilege. It is revealing of the Longfellows' elite social position, for instance, that in 1847 Fanny became the first woman in America to be given anesthesia during childbirth. Moderate in politics, liberal in religion, Professor Longfellow and his wife surrounded themselves with art, music, and books. They had dinner parties, kept up wide-ranging correspondences, and spent their summers by the shore in Nahant.

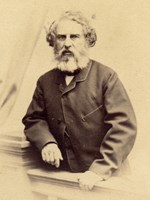

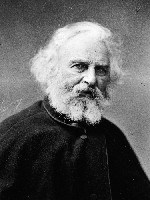

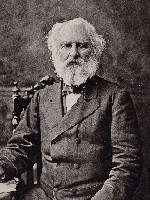

Meanwhile, Longfellow's literary career prospered and his fame spread. In this matter of his career, Longfellow must never be confused for a private citizen, a solitary scrivener, alone in his attic pouring forth his soul. Rather, throughout his writing life Longfellow had behind him the powerful New England establishment, of which as a Harvard professor and world-famous author, he became a leading representative. He counted among his friends the influential figures of the day in culture, politics, and society, and he in turn could be counted on to voice irreproachably respectable ideals grounded in moral decency and concern for the public good. As an avatar of the emerging Boston culture industry, Longfellow was not just a moral emblem but a profitable venture: his books sold extraordinarily well. He wrote prolifically, and his publishers – first Ticknor and Fields, later Houghton Mifflin – were constantly bringing out new volumes and new editions of his collected poems, at all different price points for different segments of the expanding book trade. Longfellow was frequently profiled in newspapers and magazines, and the release of poems like The Song of Hiawatha in 1854 and The Courtship of Miles Standish in 1858 were "events" shrewdly orchestrated to maximize sales. Even in his own lifetime, therefore, Longfellow was larger than life, an institution associated with an array of ideological, social, and commercial interests. Longfellow was often happiest when paying least attention to such matters, but his public aura forms a scrim against which his private self must be seen. Longfellow's domestic happiness was shattered in 1861, when his wife Fanny died of burns after fire engulfed her from a candle accidentally knocked over as she was melting wax to seal locks of her children's hair. A widower once again, never to remarry, Longfellow continued to raise the children – the oldest was fourteen, the youngest five at the time of the tragedy – and, perhaps to drown his grief, continued to write: lyric poems, the narrative poems collected in Tales of a Wayside Inn, verse dramas, and his landmark three-volume translation of Dante's Divine Comedy. His impressive output never slowing down, in the last decade of his life Longfellow published five new collections of poems, as well as assorted other writings. By the time he died, aged 75, in March 1882, at his home in Cambridge, he had become a national elder, a white-bearded eminence whose Jove-like image was widely circulated in lithographs and photographs. Sarah Orne Jewett captured something of the importance of Longfellow in the national imagination when she wrote in eulogy, "It is a grander thing than we can wholly grasp, that life of his, a wonderful life . . . . This world could hardly ask any more from him: he has done so much for it, and the news of his death takes away from most people nothing of his life. His work stands like a great cathedral in which the world may worship and be taught to pray, long after its tired architect goes home to rest."

Home and Home LifeJewett could refer so knowingly to "[t]hat life of his, a wonderful life" because its basic outlines were a point of public fascination, an indispensable part of the Longfellow legend. The patrician ancestry, the European travels, the early loss of his first wife, the Harvard professorship, the long courtship of Fanny Appleton, the five children, the historic old house in which they peaceably lived, the steadily mounting fame – these items hardly bore repeating in the popular press, so great was Longfellow's celebrity, and yet were repeated nonetheless. Craigie House (named for a former owner, Andrew Craigie, apothecary general under George Washington during the American Revolution) became a focal point of Longfellow's fame, which rested to some large extent on his life and even his lifestyle. This was a period when private life and the private home took on new public importance, and Longfellow's prestige and authority as a kind of national father figure could seem all the greater by dint of his owning such a place. The house itself, an imposing late-Georgian mansion painted a proper yellow with white trim and black shutters, bespoke affluence, dignity, and tradition. Early in the Revolutionary War it had served as Washington's military headquarters, and hence came down to Longfellow as a patriotic treasure; images of it were frequently reproduced in editions of Longfellow's works, as well as in pictorial magazines, postcards, advertisements, and such other popular media of the times as stereopticon cards. No other author's home, with the possible exception of Washington Irving's Sunnyside, could rival Craigie House in fame. With the emergence of the Colonial Revival movement in American architecture, many replica Craigie Houses appeared around the country— the first built in 1883 in Maine, the second in 1887 outside Chicago. Craigie House appeared in Longfellow's poetry too, where it comes across as a place of familial contentment. In poems like "To a Child" and "Children," Longfellow seemed to invite readers into his home, opening the door (just a crack!) onto his family life. Such glimpses gave readers the illusion that they knew the illustrious Professor Longfellow in his intimate domestic moments. In "The Children's Hour," for instance, Longfellow imagines his well-behaved daughters, "Grave Alice, and laughing Allegra, / And Edith with golden hair," granted leave to come into his famous study to play with him at the end of his work day. The father's affection is palpable. Longfellow earned the love and respect, the tenderness and reverence of his readers, then, not just as a poet but as a model husband and father, a father figure, with a privileged home life that could be glimpsed, at times, in his writing. The success of this self-representation may be judged from an 1880 letter written by the novelist Henry James to his mother; James, in London, wrote of a British lord who one day over lunch came out with the thought that "his ideal of the happy life was that of Cambridge, Massachusetts, 'living like Longfellow.'"

Reputation and PopularityLongfellow's reputation grew so large that the reputation itself became a legend, subject to all the falsehoods of the legendary. Contrary to the popular wisdom that Longfellow was almost unanimously adored in the nineteenth-century, with a few grumpy exceptions like Edgar Allan Poe and Margaret Fuller, the truth is that he was always controversial, always contested. Reviewers and editors in the newspapers and magazines took sides, often not merely on literary but on ideological grounds. The questions that concerned the critics—was Longfellow original or derivative, was he "American" enough or too European, was he "in touch" or was he too cloistered, were his metrical choices fitting? – masked deeper rifts in the country over regional influence, the ascendancy of bourgeois manners, the moral responsibilities of art and artists, and the distribution of cultural power. At the beginning of his career, for instance, Longfellow signified to many readers a welcome relaxation of the famously severe New England outlook, while for others he introduced an unwelcome note of European cosmopolitanism. By his career's end, in Victorian America, he seemed to many a stable, authoritative bulwark against accelerating change, while for others he was a staid emblem of an outmoded era. While the critics were battling it out, the public took Longfellow into their hearts. To his middleclass readers Longfellow meant not only social prestige, intellectual distinction, and moral authority, but the three together filtered through a noble but at the same time somehow approachable life, and contributing to a radiant personal aura inseparable from his poems. When the best-selling anthologist Thomas Bulfinch, for instance, wrote to Longfellow in 1855 seeking permission to dedicate his Age of Fable to him "as a sort of guarantee to the public that nothing worthless or mischievous is offered to them," he was paying homage to the way Longfellow had become not just an author but an icon, embodying impeccable honor and uprightness.

Similarly, the writer Mary Austin, growing up on the prairies of Illinois, recalled later that her parents treasured their volume of Longfellow's poetry for "the notion of mannerliness, of the gesture they missed and meant on behalf of their children, to resume"; for these transplanted New Englanders who had settled in the West, Longfellow represented a sought-after ideal of civility and civilization. Still, there were those who interpreted Longfellow more darkly: the South, especially in the years before the Civil War, tended to see in Longfellow an example of New England snobbery and hypocrisy. But even so, a "Longfellow Debating Society" was established in Clarksville, Tennessee in 1861, and a "Longfellow Dramatic Association" was founded in Baltimore in 1865. Other such Longfellow-inspired literary organizations proliferated in the decades following the Civil War, in such far-flung places as Cumberland County, Kentucky; Wheeling, West Virginia; and San Francisco. Despite (or perhaps as a result of) such expressions of Longfellow's sanctioning authority, he increasingly seemed a symbol of an oppressive cultural conservatism. The American poet Sidney Lanier left upon his death in 1885 numerous fragments and sketches for poems, one of which reads in its entirety, "Do you think the 19th century is past? It is but two years since Boston burnt me for witchcraft. I wrote a poem which was not orthodox: that is, not like Mr. Longfellow's." The rise of Modernist poets and theorists like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound in the first decades of the twentieth century finally did Longfellow in. The country had changed and so had its literary aesthetics, and Longfellow now seemed naive, sentimental, and out of touch with the hard facts of life. Opening a new chapter in his meta-life as a symbol, in the twentieth century Longfellow came to seem, in fact, not just an author whose star had waned but the very embodiment of facile, flaccid nineteenth-century poetizing; his poetry was a disaster, in this view, and his former popularity an embarrassment. Within the space of a couple decades, that is, Longfellow had gone from one of the most lauded poets who ever lived to one of the most disparaged. Suddenly now he seemed to stand for everything wrong with nineteenth-century American genteel poetry and "respectable" culture. Such a reversal in reputation, in retrospect, may be seen as yet further evidence of Longfellow's immense purity and power as a symbol, with a constantly evolving value and meaning, as if Longfellow himself and his poetry were peculiarly open to widely divergent cultural interpretation and reinterpretation. After decades of relative neglect, a new reinterpretation of Longfellow is currently taking place among poets, critics, and the general public. It seems especially noteworthy that among Longfellow's recent defenders are poets like Howard Nemerov, Dana Gioia, John Hollander, and J.D. McClatchey. McClatchey's Library of America edition of Longfellow, published in 2000, suggests that Longfellow has the power to attract a new generation of readers. Literary critics, too, have been taking a new look at Longfellow in his social and historical context, finding ways to rescue his poetry from the critical oblivion in which it languished for much of the twentieth century. Longfellow is now the subject of scholarly articles, biographies, and even historical novels, and such activity – if history is any guide – betokens the arrival of yet another phase in Longfellow's always contested fame. Articles |

Last updated: November 2, 2021