Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

How do we know if parks are healthy? We measure their vital signs, of course! Across the country, there are 32 inventory and monitoring networks that measure the status and trends of all kinds of park resources. We're learning a lot after years of collecting data.

These articles are a part of a collection, or special issue, of Frontiers for Young Minds, an international online journal of science written for kids and involving kids in the review process. Taking the Pulse of U.S. National Parks presents what we are learning from years of monitoring plants and animals and physical conditions in parks. The articles featured here are results from Central Alaska parks.

Frontiers for Young Minds

It Takes a Pack to Raise a Pup

Wolves are important to keep ecosystems healthy. For wolf populations to thrive, pups need to survive into adulthood. Wolf pups can be harmed, even killed, by wolves from outside their pack. To protect the pups, some wolves in the pack must stay at the den and guard the pups. But some of the adults must leave the den sometimes, to hunt for food and to keep other wolves out of the pack’s territory. By monitoring and studying wolves for many years across North America and in Alaska’s national parks, we are learning how wolves divide these tasks. We know that the mother wolves care for their pups for the first several weeks while nursing, but once the pups no longer need milk, all pack members share in taking care of the pups. We have come to understand that all wolves are important to the success of the pack.

Also see: monitoring wolves in central Alaska

Sorum, M., J. Pruszenski, and B. Borg. 2022. It takes a pack to raise a pup. Frontiers for Young Minds 10: 735160.

Frontiers for Young Minds

The Wild and Wonderful World of Stream Bugs

Under the surface of most streams a strange world exists, made up of hundreds of small critters called aquatic invertebrates. “Aquatic” means they live in the water and “invertebrate” means they have no backbones or even skeletons. Some have body parts that look like they came from an alien planet. Some have slippery bodies adapted to rushing stream water. These organisms play many important roles. Some live for up to 7 years and others live for as little as 2 weeks. Some eat slime growing on stream rocks and others eat leaves. Some, like the golden stonefly, even stalk and eat other invertebrates, like a tiger in a jungle. In national parks and around the world, scientists use these insects, worms, leeches, and mites to tell if the water is healthy. We can do this because certain stream invertebrates disappear if water is polluted, or if the stream habitat is degraded.

Also see: Monitoring streams and rivers in central Alaska

Simmons, T., E.C. Dinger, and E. W. Schweiger. 2022. The wild and wonderful world of stream bugs. Frontiers for Young Minds 10: 716573.

Frontiers for Young Minds

The weird and wonderful variety of bugs that live in streams is more than cool—it is a great scientific tool. The mixture of bugs helps scientists understand water quality, which means whether the water is clean or dirty. Two kinds of tools translate bug variety into measures of stream health. One is called a multimetric index; the other is called an observed-to-expected index. The multimetric index “speaks bug” to us. It uses bug preferences for food and habitat, tolerance for pollution, and other bug attributes to decipher whether a stream is to a bug’s liking. The observed-to-expected index uses scientists’ knowledge of which bugs usually occur in clean water, to predict which should be present in a good-quality stream. Both indices give us the big picture of water quality and help scientists track the health of streams in U.S. national parks.

Also see: Monitoring streams and rivers in central Alaska

Dinger, E. C., E. W. Schweiger, and T. Simmons. 2022. How healthy is a stream? Ask the stream bugs! Frontiers for young Minds 10: 716591.

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

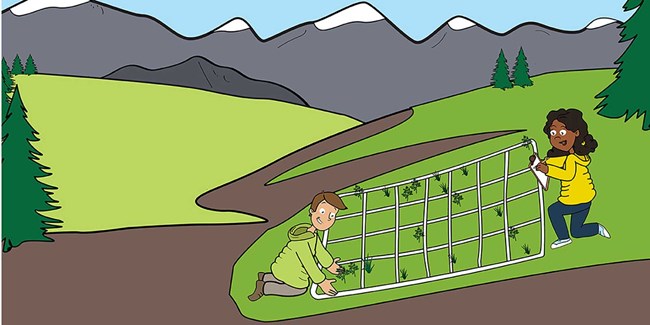

A recipe for plant diversity in subarctic Alaska

Hungry for a little plant diversity? Let us mix some up! First, we gather available ingredients—a bit of soil, a few nutrients, and a selection of nearby plants. Then, we add them together, pour them onto a landscape and let our concoction sit. Sound easy enough? But wait… was that soil we used too acidic? Did we add enough liquid? Was our landscape flat or tilted? How can we adjust our recipe to grow the most plant species in one place? As plant ecologists, we travel to remote places in subarctic Alaska to look at which species grow there. At each place, we record the condition of the environment and tally the number of plant species we find. Over 1,000s of visits, we now have a pretty good recipe for cooking up plant diversity! By learning about where plant diversity is high now, we can help protect it into the future.

Also see: vegetation structure and composition monitoring in Central Alaska

Stehn, S. and C. Roland. 2022. A Recipe for Plant Diversity in Subarctic Alaska. Frontiers for Young Minds 10:703708. doi: 10.3389/frym.2022.703708

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

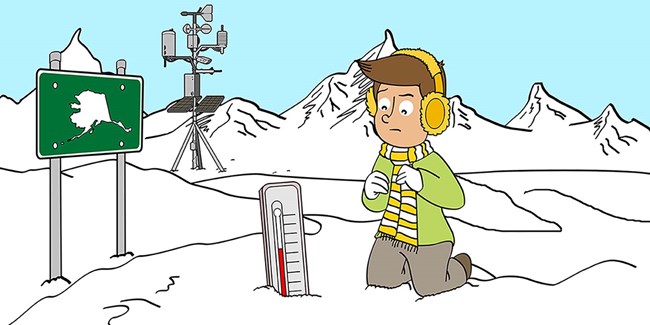

Two degrees matters

How do you tell if someone is not well? You take the person’s temperature. If it is too warm, something is not quite right. We care about how the weather and climate are changing in Alaska’s national parks, so we continuously take their temperatures. We have dozens of weather stations in remote locations in the northern Alaska parks that run continuously, powered by the sun. Over the past several years, we found that the air and ground temperatures have been warmer than normal. Plants, animals, and people get used to living in their environments. They thrive within an expected temperature range. Things get out of whack when the environment that organisms are accustomed to changes. In northern Alaska, warming of just a few degrees can cause ice to melt and formerly frozen ground to thaw. Once the ground thaws, the ice changes to water and the landscape changes.

Also see: climate monitoring in the Arctic, permafrost monitoring in the Arctic, climate monitoring in Central Alaska, permafrost monitoring in Central Alaska, climate monitoring in Southwest Alaska, climate monitoring in Southeast Alaska, high-latitude climate change

Hey Teachers! Check out this lesson plan.

Sousanes, P., K. Hill, and D. Swanson. 2022. Two Degrees Matters. Frontiers for Young Minds 10:719108. doi: 10.3389/frym.2022.719108

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

The recovery of the American peregrine falcon in Alaska

American Peregrine Falcons nesting along Alaska’s upper Yukon River have been studied for nearly 50 years. Peregrine populations decreased in the 1960’s because widespread use of the insecticide DDT caused their eggshells to thin. Thin eggshells meant that eggs crushed easily in the nest, which reduced the number of baby birds produced. Eventually, Peregrine Falcons were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in the United States (U.S.). After the U.S. banned the use of DDT, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and others helped Peregrine Falcons recover. Today, upper Yukon River Peregrine Falcons have rebounded and are thriving. The Peregrine Falcon’s recovery in the U.S. is a shining success story of the Endangered Species Act, although climate change and other pollutants create continuing challenges for the species.

Also see: Peregrine Falcon monitoring in Central Alaska

Payer, D. and M. Flamme. 2022. The Recovery of the American Peregrine Falcon in Alaska. Frontiers for Young Minds 10:714834. doi: 10.3389/frym.2022.714834

Last updated: April 23, 2024