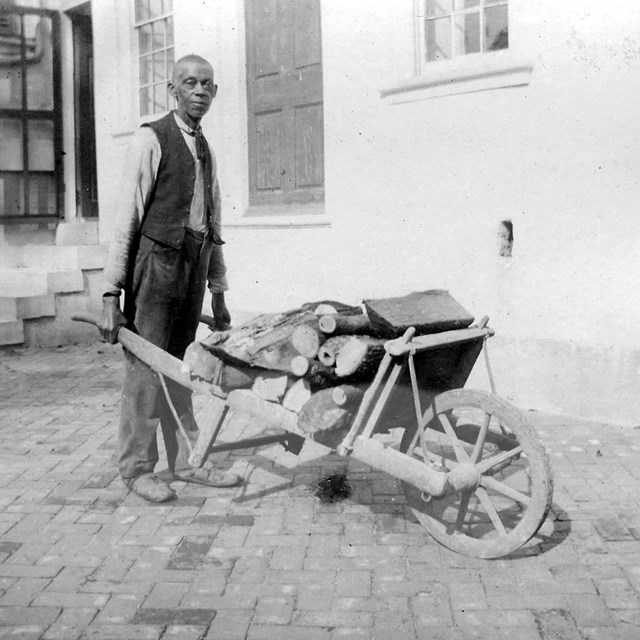

NPS The Toogood family left a lasting impression on the Ridgely family from what it seems in documentation. Multiple accounts speak about how good Dinah Toogood's food was good. Nick Toogood played a pivotal role as a spiritual leader among the enslaved people at Hampton. Nick worked as a handyman and was very charismatic. In leading mourners of the burial of another enslaved person, Bill Davis, Nick struck a favorite hymn—one that he normally sang as he called hogs to feed at the troughs. Unfortunately, for the procession, when the pigs heard and recognized his voice, they came running scattering the mourners. James McHenry Howard commented in 1894 that Nick "was a sort of spiritual leader among the [enslaved at Hampton] & if anything in the way of religious ceremonial or worship was going on, Nick was sure to have a prominent place." Howard also recounted an episode showing an example of resistance to enslavement:

This could have been Nick's way of showing some sort of form of resistance. Despite the dehumanization of chattel slavery, this was a small way of showing his humanity. Both Dinah and Nick continued to be held in chattel slavery until the 1864 Maryland Emancipation. Seventy-year-old Nicholas and sixty-year-old Dinah moved 13 miles away from Hampton to Baltimore City around 1865. They moved into a community that was one of the most active in the struggle for civil rights where they lived until their passing over ten years later. They worked as laborer and laundress while attending the Orchard Street Church (Methodist Episcopal). While at church they would witness speeches, conferences, educational achievements and other gatherings by the nation’s most ardent seekers of full rights for African Americans. By 1867 they were listed in the Baltimore City Directories living at 108 Orchard Street in what is now the Seton Hill neighborhood. This area was an important one in the community of freed Africans Americans living in the city. Orchard Street was a center of Baltimore’s free Black community. The Orchard Street ME Church figured heavily in Baltimore’s African American history. It was said to have been a heavily used station on the Underground Railroad. It also housed an early school for African Americans and served as a lyceum hosting local and regional organizational rallies and fundraisers. One of the church’s well-known parishioners and neighbor of the Toogoods was Rev. Samuel Green of the Eastern Shore who gained some stature for having been imprisoned for five years for possessing a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

NPS The elderly Toogoods survived chattel slavery to spend their last years as freed people in a vibrant community engaged in self-help and attainment of the rights of its once enslaved residents. As members of the church, they would have been involved in some activities. The January 1879 obituary for Nicholas stated that his funeral services were held at Orchard Street Church where he had been a member. Dinah continued to reside on Orchard Street at least through 1885, when she passed away. Learn More

|

Last updated: August 5, 2024