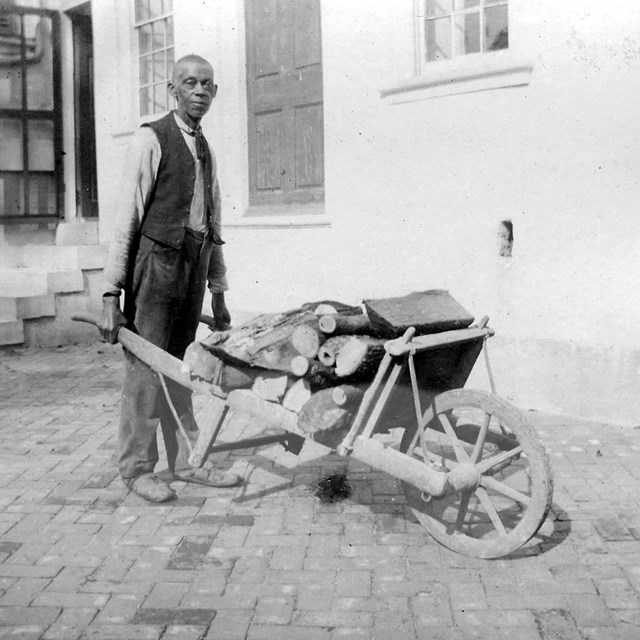

c. 1895, NPS Many former plantations went bankrupt after the Civil War. Hampton was an exception, although profits were usually minimal. By the early 20th century, Helen Stewart Ridgely’s inherited income was needed to pay the estate’s bills. Two sets of brothers worked as paid farm laborers at Hampton after the Civil War. Daniel (1848-lv. 1910) and Sam Brown (1846-lv. 1880) were younger brothers of Nancy Brown Davis who was an enslaved person that was a house servant. Daniel and Sam worked at the Home Farm in the 1870s and 1880s. Jim (1834-1902) and Joe Pratt (1832-lv. 1882) had formerly been enslaved laborers, later becoming paid workers; their duties included harvesting and shucking corn.

Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1880; Image courtesy Newspapers.com Former head seamstress Harriet Hawkins (c.1807-lv.1886) found work as a dressmaker to the wealthy ladies of the Mount Vernon neighborhood. One of her sons, Nelson (1843-1916), a waiter and cook at Hampton, became a “famous” caterer (advertised in newspaper above), eventually moving to Philadelphia.

c. 1890, Maryland Center for History and Culture, PP240 Click to learn more about the Cummings Family

NPS Click to learn more about the Toogood Family People

c. 1895, NPS. Learn more about the structures on the home farm at Hampton. Learn More

|

Last updated: August 12, 2024