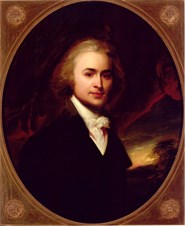

No American who ever entered the presidency was better prepared to fill that office than John Quincy Adams. Born on July 11, 1767 in Braintree, Massachusetts, he was the son of two fervent revolutionary patriots, John and Abigail Adams, whose ancestors had lived in New England for five generations. Abigail gave birth to her son two days before her prominent grandfather, Colonel John Quincy, died so the boy was named John Quincy Adams in his honor. Through the example of his father and mother the child learned the sacrifices that individuals need to make to preserve and protect the welfare of society. When John Quincy Adams was seven years old, his father traveled to New York to participate in the First Continental Congress. There, representatives from the American Colonies met to discuss their opposition to England's Colonial Government. In 1775 a second Continental Congress was convened in Philadelphia to continue to debate the issue of independence. From Philadelphia John wrote to Abigail of the Congress' activities and of their duties, as parents, to educate a new generation of Americans. John wrote: "Let us teach them not only to do virtuously, but to excel. To excel, they must be taught to be steady, active and industrious." John Quincy's parents succeeded in their objective, for not soon after, the young Adams wrote that he was working hard on his studies and hoped "to grow a better boy." War soon forced young John to mature at even a more accelerated rate. News quickly spread to the Adams farm in Braintree of the battles fought between the American Colonists and the British in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. Abigail and her son were eager to learn more about the progress of the war in order to inform John Adams in Philadelphia of the events that were transpiring in the Boston area. On June 17, 1775 they were told a major battle was underway in Boston. Abigail took her son to the top of Penn's Hill, near their farm, and they watched the fires of Charlestown and heard the cannons roar from the Battle of Bunker Hill. Experiencing the battles of the Revolutionary War around Boston in 1775-1776, and reading his father's letters from Philadelphia about the struggle to declare independence, John Quincy Adams was literally a child of the American Revolution. He absorbed in his earliest memories the sense of destiny his parents shared about the United States and dedicated his life to the republic's consolidation and expansion. At age ten, John Quincy accompanied his father on a dangerous winter voyage to France. John Adams was sent to Europe as a Commissioner to negotiate for peace with Great Britain. He took his son on the diplomatic mission in order to give the boy international experience and provide for a second generation of enlightened leadership in U.S. foreign relations. While crossing the Atlantic the ship was struck by lightning (killing four of the crew), survived a hurricane, and fought off British vessels. Returning to America a few months later, John Quincy perfected his French by teaching English to the new French Minister to the United States. When his father was sent back to Europe to do diplomatic service, he again took John Quincy Adams. The second ocean crossing proved as eventful as the first, when the boat sprang a leak and John Quincy and the rest of the crew had to man the pumps as the unseaworthy vessel barely reached the Spanish coast. A fascinating, but grueling journey of two months across Spain and France returned them to Paris in February of 1780. In that year, John Quincy traveled to Holland in order to attend Leyden University and began to keep a diary that forms so vital a record of the doings of himself and his contemporaries through the next 60 years of American History. John Quincy Adams certainly benefited from his father's association with the other U.S. representatives in Europe. The young Adams often sat in on conversations between his father and Benjamin Franklin and was so fond of Thomas Jefferson that John Adams later wrote that: "he (John Quincy) seemed as much your (Thomas Jefferson's) son as mine." While John Quincy Adams, so far, had been a spectator of the events that were shaping America's destiny, his mother in a letter from three thousand miles away, urged her son to actively confront the extraordinary challenges that the times demanded, saying: "These are the times in which a genius would wish to live. It is not in the still calm of life, or the repose of a pacific station, that great characters are formed.... Great necessities call out great virtues. When a mind is raised and animated by scenes that engage the heart, then those qualities, which would otherwise lie dormant, wake into life and form the character of the hero and the statesman." The opportunity soon arose for John Quincy to actively serve his country. In 1781, he accompanied Francis Dana to Russia. Dana was appointed by the Continental Congress as the U.S. Minister to Russia and brought the young Adams along as his private secretary and interpreter of French. This mission would take John Quincy on two more long and arduous journeys across Europe, in between which he wrote and translated for Dana and pursued his own studies of history, sciences and languages. Upon his return to France, in 1783, the young Adams served as an additional secretary to the U.S. commissioners in the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris that concluded the American Revolutionary War. The next year, after his family was reunited in France and his father was appointed U.S. Minister to Great Britain, John Quincy Adams returned to America to attend Harvard University. Adams sought to become an attorney like his father, and upon graduation, in 1787, read law at Newburyport, Massachusetts under the tutelage of Theophilus Parsons. In 1790, John Quincy was admitted to the Bar in Boston and formally became a practicing attorney. While struggling as a young lawyer John Quincy resumed his preoccupation with public affairs by writing a series of articles for the newspapers in which he criticized some of the doctrines in Thomas Paine's book, "Rights of Man". In a later series he skillfully supported the neutrality policy of the Washington Administration as it faced the consequences of a war between France and England in 1793.

John Quincy Adams Early Diplomatic Career When John Adams was elected President in 1797, he appointed his son as U.S. Minister to Prussia (which consisted of portions of present day Germany and Poland). Before John Quincy Adams left for Prussia, he traveled to England in order to marry Louisa Catherine Johnson, the daughter of Joshua Johnson, who served as the United States' first Consul to Great Britain. Louisa was born and raised in Europe and is the United States' only foreign-born First Lady. While she was not as strong in spirit as Abigail Adams, Louisa brought other qualities to her marriage that made her an ideal partner for John Quincy Adams. The future First Lady's charm and warmth endeared her to all she met, and offset John Quincy's cold and serious manner. The affirmation of Louisa Catherine's popularity as First Lady was the adjournment of both the Senate and the House of Representatives upon her death in 1852. John Quincy Adams and his new bride traveled to Prussia after their wedding in 1797. Before Adams started his duties as U.S. Minister, he took his wife on a trip through part of Prussia called Silesia (today part of Poland). The countryside in this region reminded John Quincy of his home far away in Braintree and Louisa received her first glimpse of what the terrain in Massachusetts was like. After this brief trip John Quincy set out to improve relations between the U.S. and Prussia. In order to achieve this objective, Adams worked hard to master the German language, the native tongue of Prussia, and he translated a number of articles from German to English to perfect his ability. Fluency in Prussia's native language made John Quincy's diplomatic work easier and he successfully concluded a Treaty of Amity and Commerce in Prussia's capital city of Berlin in 1799. Statesmanship At Home and Abroad Actually, John Quincy Adams was never a strict party man. Ever aspiring to higher public service, he considered himself "a man of my whole country." As U.S. Senator, Adams approved the Louisiana Purchase (1803), refused to take a pro-British stance as the Napoleonic Wars reached their climax, and increasingly aligned himself with the policies of Thomas Jefferson's Secretary of State, James Madison. John Quincy's adherence to his own principles in supporting President Jefferson's Embargo Act (1807), at once gained him the gratitude of the Republican Party, the bitter hostility of the Federalists; and 150 years later - a place in John F. Kennedy's book, Profiles in Courage. Although Adams understood that the Embargo was extremely unpopular in New England because of its harmful effect on the region's economy, he bravely supported the measure because he felt it was the best method to gain British respect of American maritime rights. Adams' devotion to the nation's interest made him an easy target for sectionalist politicians in Massachusetts, who conspired to oust the young Senator at the next election. John Quincy's successor was chosen on June 3, 1808, several months before the usual time for electing a senator for the next term, and five days later Adams resigned. In the same year he attended the Republican congressional caucus, which nominated James Madison for the presidency, and thus loosely allied himself with the Republican Party. From 1806 to 1809 Adams was Boylston professor of rhetoric and oratory at Harvard College. In 1809 President Madison appointed John Quincy Adams as the first United States Minister to Russia. Adams arrived in Russia's capitol city of St. Petersburg at the time when Tsar Alexander broke off his alliance with Napoleon. John Quincy therefore met with a favorable reception and was told by Alexander that Russia would do all in its power to further the interests of U.S.-Russian relations. The Tsar fulfilled his promise and with the hard work of Adams the United States soon surpassed England as Russia's leading trading partner. From his vantage point in St. Petersburg, John Quincy watched and reported to Washington of Napoleon's invasion of Russia and the final disastrous retreat and dissolution of France's grande armée. On the outbreak of war between England and the United States in 1812, John Quincy became involved in efforts to negotiate an end to hostilities. That September, the Russian government suggested that Tsar Alexander was willing to act as mediator between the two belligerents. While England refused the Russian mediation offer, they eventually entered into direct negotiations with the United States. John Quincy Adams was one of the U.S. representatives at these negotiations, which started in August of 1814, and resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24 of that year, that ended the War of 1812. Adams then visited Paris, where he witnessed the return of Napoleon from Elba for the Hundred Days War. The French Emperor was ultimately defeated at Waterloo. From Paris, John Quincy Adams traveled to London where he and two other U.S. representatives (Henry Clay and Albert Gallatin) negotiated a "Convention to Regulate Commerce and Navigation" with Great Britain. John Quincy completed his long and brilliant career as a diplomat by serving for two years as U.S. Minister to England, a post held by his father after the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain and later to be held by his son, Charles Francis Adams, during the United States Civil War. In 1817, John Quincy returned to the United States to become Secretary of State in President James Monroe's Administration. John Quincy's service there, 1817-1825, has rightfully earned him standing as one of the United States' finest Secretaries of State. He guided negotiations with Great Britain that resolved the remaining disputes between the two countries and began an era of friendly relations between both nations, which continues today. Included in the settlement was a prohibition on armaments, along the border of the United States with Canada that has made it the longest-lasting unfortified boundary in the world. He also arranged for the purchase of Florida from Spain and negotiated a transcontinental treaty with that nation which established the boundary between Spanish and American possessions from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. He guided U.S. efforts aimed at resisting European efforts to thwart independence movements in the New World that resulted in the pronouncement of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. Adams was proud of his accomplishments in the State Department; regarding them as fulfilling the goals of the new nation that he had seen take shape in the battles around Boston a half-century earlier. These goals included equal standing in the family of nations, security within transcontinental boundaries, and sympathy for the national independence and republican aspirations of all the countries of the New World.President of the Whole Nation As John Quincy Adams assumed office he acknowledged to the American people that he was "less possessed of your confidence in advance than any of my predecessors," but he promised to make up for this with "intentions upright and pure, a heart devoted to the welfare of our country, and the unceasing application of all the faculties allotted to me to her service." In his first message in December of 1825, John Quincy set forth his vision for the United States asserting "The great object of the institution of civil government, is the improvement of the condition of those who are parties to the social contract." Within this perception Adams had little use for those who favored states rights' at the expense of the common national good. In particular, the president recommended establishment of a national university and national naval academy to help train the wise and patriotic leadership he thought the country needed. Adams also advocated an extensive system of internal improvements (mostly canals and turnpikes) to be paid for out of increasing revenues from western land sales and a continuing tariff on imports. He called too for the establishment of a uniform system of weights and measures and the improvement of the patent system, both to promote science and to encourage a spirit of enterprise and invention in the United States. In a further effort to support science and spread its benefits to the nation and to the world, Adams advocated not only an extensive survey of the nation's own coasts, land and resources but also American participation in worldwide efforts for "the common improvement of the species." John Quincy's ambitions for the improvement of science were not limited to this planet, he urged the building of an astronomical observatory (light-houses of the skies) so the United States could make at least one such contribution to the advancement of knowledge to supplement the 130 observatories that had already been constructed in Europe. While today we may view President John Quincy Adams' plans for the United States as far- sighted, they were perhaps over ambitious and unrealistic for 1820's America. His proposals were greeted with scorn and derision, regarded as efforts to enlarge the power under his control and to create a national elite that would neglect the common people and destroy the vitality of state and local governments. Personal tragedy compounded John Quincy's political woes when on July fourth, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the formal adoption of the Declaration of Independence, his father died. The death of his father, always his staunchest political and personal ally, left Adams more isolated than ever. It was unfortunate that at this time John Quincy faced his greatest challenges politically, because his Jacksonian enemies had won control of both Houses of Congress in the election of 1826. Appropriations for internal improvements fell far short of the amount that President Adams requested from Congress. A new tariff, enacted in 1828, sponsored by both Administration and anti-Administration congressmen from the Middle and Western states, was not the useful and fair measure that Adams had intended it to be. The bill was poorly drawn, and because of its concessions to the extreme protectionists the Southern cotton interest called it the "tariff of abominations." Yet Adams signed it. As his presidential term progressed, John Quincy Adams' best intentions for the improvement of his nation seemed to always meet with failure. He refused to sign a fraudulent Indian treaty by which the Creeks were to be removed from all their lands in Georgia. But his scrupulous concern for the rights of Native Americans irritated both Southerners and Westerners. Even in foreign affairs, despite John Quincy's vast experience, the Administration failed to achieve its goals. In 1826, chiefly for partisan reasons, Congress obstructed Secretary of State Henry Clay's attempt to send U.S. delegates to a conference in Panama, which aimed at building closer ties between the nations of the Western Hemisphere. Adams also failed to persuade the British to open their West Indian islands to U.S. trade. At home, while his foes continued their relentless attack, John Quincy Adams further weakened his position by spurning the role of party leader and refusing to use the patronage weapon in his own defense. Adams was, in fact, the last of the Presidents to look upon parties as an evil and to adhere to the eighteenth-century ideal of a national consensus with himself as its spokesman. While John Quincy Adams was adverse to party politics, Jacksonian partisans articulated and brought into existence a new, positive idea of political party. They saw political parties as manifestations of the needs and interests of the people of a free society. The job of the party and its leaders was to accept, enlarge, and fulfill the aspirations of the multitude of factions and mold them into a political instrument that could gain national power. Under this new ideology of party, Martin Van Buren organized the Democratic Party around the objective of electing Andrew Jackson president in 1828. In contrast to President Adams who regarded "politicking" as beneath the dignity of the office, Jackson's supporters organized and gathered their forces in order to win the election. By mid-1828 the campaign became increasingly hostile, and it was clear that the tide was running strongly for the Jacksonians. Supporters on both sides tried to use the press to circulate scandalous stories about the opposition candidate in hopes of getting their man elected. New England, and some of the Mid-Atlantic States, remained loyal to Adams, but the Jacksonians used their superior organization to capitalize on the burgeoning sectional and democratic trends of the country. When the returns were in, Jackson had gained a 178 to 83 victory in the electoral college and had a 647,276 - 508,064 margin in the popular vote. The John Quincy Adams presidency, then, somewhat like that of his father, ended in frustration and a sense of having lost a vital battle to new, and to the Adamses, unwelcome political forces. The tragedy of this loss was compounded soon after the election by the death of John Quincy's oldest son, George Washington Adams. Virtually penniless, grieving over the death of his son, and believing his political career to be over, Adams retired to Quincy to seek solace in his garden and his books. Return to Washington Throughout, he was an ardent opponent of the expansion of slavery. In 1839 he presented to the House of Representatives a resolution for a constitutional amendment providing that every child born in the United States after July 4, 1842, should be born free; that with the exception of Florida, no new state should be admitted into the Union with slavery; and that neither slavery nor the slave trade should exist in the District of Columbia after July 4, 1845. The "gag rule," a resolution passed by Southern members of Congress against all discussion of slavery in the House of Representatives, effectively blocked any discussion of Adams' proposed amendment. His prolonged fight for the repeal of the gag rule and for the right of petition to Congress for the abolition of slavery was one of the most dramatic in U.S. legislative history. Adams contended that the gag rule was a direct violation of the First Amendment to the Federal Constitution, and he refused to be silenced on the question, despite the bitter denunciation of him by opponents. At each session of Congress the majority against him decreased until, in 1844, his motion to repeal the gag rule of the House was carried by a vote of 108 to 80, and his long battle was over. Another spectacular contribution of Adams to the antislavery movement was his championing of the cause of the Africans of the slave ship Amistad. The Africans on this ship were being held captive by Spanish slave merchants who planned to sell them as slaves, but before the ship reached port the brave Africans revolted and escaped from their captors by bringing the ship into U.S. waters near Long Island, New York. Adams successfully defended the Africans as freemen before the Supreme Court in 1841 against efforts of the administration of President Van Buren to return them to their captors and to inevitable death. Fighting slavery did not imply neglect of other interests for John Quincy Adams. His love of science still continued and in 1844, at the age of seventy-seven, he traveled to Cincinnati to lay the cornerstone of an observatory. In 1846, he was largely responsible for the grant of a Congressional charter to the Smithsonian Institution, the earliest American foundation for scientific research. The respect in which he was held was demonstrated that same year when, after a stroke kept him away from Congress for several months, he received an ovation on his return. On February 21, 1848, in the act of protesting the U.S.-Mexican War, John Quincy suffered a second stroke, fell to the floor of the House and died two days later in the Capitol building. The Legacy of John Quincy Adams Today, the Adams National Historical Park serves as a setting to investigate the role that John Quincy Adams played in establishing and perpetuating the American democratic tradition. John Quincy Adams' life and that of his family are vividly interpreted by National Park Service Rangers using the three historic residences that comprise the site as backdrops to tell the story. Visitors can witness first hand the environment that shaped the character and ideas of John Quincy Adams and his family. The National Park Service conscientiously preserves these houses and the property around them to provide present and future generations with a window to view an American family who contributed to their country through public service. |

Last updated: April 30, 2015