Last updated: August 22, 2024

Lesson Plan

A Woman's Place Is In This House: Alice Paul and the Work For Women's Equality

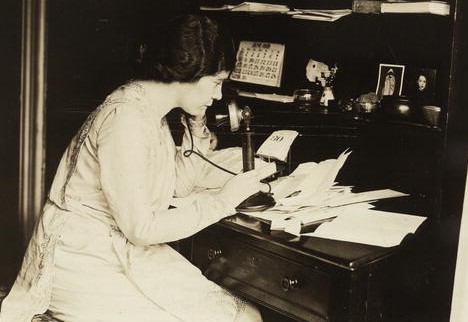

Alice Paul was a prominent leader in the women's rights movement.

Library of Congress

- Grade Level:

- Middle School: Sixth Grade through Eighth Grade

- Subject:

- Social Studies

- Lesson Duration:

- 90 Minutes

- Common Core Standards:

- 6.W.1.a, 6.W.1.b, 6.W.6, 6.W.8, 7.W.6, 7.W.7, 8.W.1, 8.W.1.b, 8.W.7, 8.W.8

- State Standards:

- United States History

Era 7: Emergence of Modern America 1890-1930

Standard 3A: The student understands the cultural clashes and their consequences in the postwar era.

Standard 3D: The student understands politics and international affairs in the 1920s - Additional Standards:

- Social Studies

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

Standard E-Explains and analyzes various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

Standard F-Identifies and explains the roles of political actors in influencing public policy - Thinking Skills:

- Understanding: Understand the main idea of material heard, viewed, or read. Interpret or summarize the ideas in own words. Applying: Apply an abstract idea in a concrete situation to solve a problem or relate it to a prior experience. Analyzing: Break down a concept or idea into parts and show the relationships among the parts. Creating: Bring together parts (elements, compounds) of knowledge to form a whole and build relationships for NEW situations. Evaluating: Make informed judgements about the value of ideas or materials. Use standards and criteria to support opinions and views.

Essential Question

How can people work for change? What methods do they use? What is the importance of location (where you are) in the struggle for equality?

Objective

Students will identify locations on a street map using accompanying text. They will search a database to find historical photos of the corresponding locations. Using what they have discovered, they will analyze the connection between location and methods of working for change. Taking it further, the students will identify an issue they would like to advocate for and describe a corresponding location to work for that change.

Background

Alice Paul and the Work of Women's Equality: A Series of Lesson Plans

In 1929, the leaders of the National Woman’s Party (NWP) bought a house on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. to be their new headquarters.They named the building after NWP President and primary benefactor, Alva Belmont. In the previous decade, NWP members picketed the White House and went to prison for their political activism in support of woman suffrage. Many of the suffrage veterans declared victory with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which reads: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” Alice Paul, the founder of the NWP, believed that winning the vote was not the end. For her, the struggle continued, now with the power of the ballot on their side.

“It is incredible to me that any woman should consider the fight for full equality won,” Alice Paul declared in 1920. “It is just beginning. There is hardly a field, economic or political, in which the natural and unaccustomed policy is not to ignore women.” She called on women to continue the work for equality. “Unless women are prepared to fight politically, they must be content to be ignored politically.”

The National Woman’s Party took advantage of their strategic location near the Capitol in their work for women’s equality. Alice Paul was dedicated to changing laws that treated women differently than men which, she believed, kept women from being free and equal citizens. Paul lived at the Alva Belmont House when she was working in Washington, D.C.. Paul and the NWP lobbied Congress to support federal legislation to address women’s social, political, and economic inequality. They supported women running for elected office. They also proposed another amendment to the U.S. Constitution known as the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which Paul drafted in 1923.

The women of the NWP used the political skills they developed during the fight for the Nineteenth Amendment to pursue their goals. One tactic they stopped using after winning the vote, however, was the confrontational protests that the public associated with the NWP during the campaign for woman suffrage. They no longer picketed or staged political stunts. They worked for change using other methods of political persuasion.

These lessons help students examine different tactics used by the National Woman’s Party in their continued campaign for women’s equality. Throughout the series of activities, students analyze the tensions between the goal of legal equality and the role of laws meant to protect women. They identify opposing perspectives and develop arguments to address those concerns. Using what they discover, students can conduct their own oral history and plan their own campaign for change.

Preparation

Map Activity

Alice Paul moved to Washington, D.C. in December 1912 to chair the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) Congressional Committee (CC). The purpose of the CC was to lobby for passage of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution enfranchising women. Alice Paul rented a basement office at 1420 F Street, NW [1]. From this office, she organized the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession down Pennsylvania Avenue on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration. After the procession, Paul began to clash with NAWSA leadership and formed a separate organization called the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage(CU). The CU eventually ended its affiliation with NAWSA and continued to lobby for passage of the suffrage amendment from the F Street office.

In January 1916, the CU moved from the F Street office to the Cameron House (now known as the Benjamin Tayloe House) at 21 Madison Place, NW [2]. From this headquarters, they launched a campaign across the country aimed at women voters in the West, urging them to vote against Democrats since the party had done little to advance the woman suffrage amendment. For this campaign, the CU formed the Woman’s Party, a party for women voters. In 1917, the CU officially changed its name to the National Woman’s Party (NWP). From the Madison Place headquarters, the NWP began its new strategy: picketing the White House to convince President Wilson to support the amendment. (For a lesson plan devoted specifically to the National Woman’s Party fight for passage of the 19th Amendment see the Teaching with Historic Places lesson: Lafayette Park: First Amendment Rights on the President’s Doorstep.)

After the U.S. entered World War I, the NWP’s criticism of the President drew angry crowds who became violent towards the protestors. Picketers were often arrested and many spent time in prison. The NWP was evicted from the Cameron House headquarters by their landlord. They moved across Lafayette Square to 14 Jackson Place [3]. From this location, they continued organizing protests and lobbying campaigns until the successful passage and ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

In 1921, through the generous donation of their president, Alva Belmont, the NWP purchased a new headquarters at 21 First Street, NE [4]. This historic building, known as the Old Brick Capitol, was the place where Congress met while the U.S. Capitol was rebuilt following its burning by the British during the War of 1812. It also served as a prison during the Civil War. But after the NWP’s investment in renovating the property, the federal government seized it through eminent domain, which is the power of the government to take private property and convert it into public use. The government demolished the property in order to build the Supreme Court building. The NWP lawyers negotiated a generous payout from the government and with the proceeds purchased the property at 144 B Street, NE (now Constitution Avenue), their fifth and final headquarters [5]. From this headquarters, they continued their lobbying campaign for women’s equality, including for passage of the Equal Rights Amendment.

This house is now the site of the Belmont-Paul Women's Equality National Monument.

For more information and timeline, visit the Library of Congress National Woman’s Party Detailed Chronology.

Materials

A map of the east end of the National Mall and surrounding streets, including the U.S. Capitol and the White House. Locations of the five [5] headquarters of Alice Paul's organizations are noted with numbers

Download Street Map of Downtown Washington, D.C.

Lesson Hook/Preview

What do you want to change?

Throughout the history of the United States of America, women and men have worked and struggled to change laws and society when they recognized that something was wrong. These activists have used many different methods to try to bring about that change. How did they do it?

In this activity, you will examine some of the ways that Alice Paul and other women suffragists worked for the right to vote and to be treated equally.

Procedure

Questions:

1) Locate and label the following on the map:

2) Analyze:

Why do you think Alice Paul and the CC/CU/NWP chose each of these headquarters?

What connections do you see between the locations of their offices and the strategies they used to work for change?

3) Research:

Search the Library of Congress Women of Protest pages to find photographs of each of the headquarters described above.

Now search for examples of the strategies used to by women to work for passage of the woman suffrage amendment. For example, search for "picket," "lobby" or "prison." Choose two photographs and describe what you see in the pictures.

How do you think the actions shown in the photographs you chose might help women win the right to be treated equally?

4) Expand:

What issue is important to you?

Where would you set up your headquarters if you wanted to work for the change you identified? (You are not limited to the areas shown on the map, or even to Washington, D.C.)

Explain your choice and describe how you would use your headquarters to work for this change.

Vocabulary

affiliation -connection with a larger organization

amendment -an addition or change to a constitution

enfranchise to give the right to vote

legislation- the act of making laws

lobby-to try to persuade a politician or public official about an issue

ratification the act of signing or agreeing to a treaty, contract, or amendment

suffrage-the right to vote

suffragist -someone who believes in the right to vote and works to expand that right to more people, especially women

Assessment Materials

Where Do We Work for Equality?Students present what they discovered during their research. The rest of the class asks questions about what they found.

Each student or group chooses one photograph that they discovered during their research.

Ask them to describe to the teacher or the class what the photograph shows.

After they provide the description, ask the student/group or the rest of the class what questions they have.

Write the questions on the board or on an easel.

Return to the questions after subsequent activities to determine if the class has found the answers. Use the questions for further discussions.

Additional Resources

Fighting for Equality: Historical Context

Adapted from the essay “Beyond 1920: The Legacies of Woman Suffrage,” by Liette Gidlow

On August 26, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment officially became part of the United States Constitution. The culmination of seventy-two years of struggle by several generations of activists, the amendment officially eliminated sex as a barrier to voting throughout the United States. Woman suffragists had persisted through countless trials and humiliations to get to this moment. Not only had they spoken out, organized, petitioned, traveled, marched, and raised funds; some also had endured assault, jail, and starvation to advance the cause. Now the right to vote was finally won.

The Nineteenth Amendment expanded voting rights to more people than any other single measure in American history. And yet, the legacy of the Nineteenth Amendment, in the short term and over the next century, turned out to be complicated. It advanced equality between the sexes but left intersecting inequalities of class, race, and ethnicity intact. It helped women, above all white women, find new footings in government agencies, political parties, and elected offices--and, in time, even run for president--and yet left most outside the halls of power. The Nineteenth Amendment became a crucial step, but only a step, in the continuing quest for equality and for more representative democracy.

Full suffrage expanded the opportunities for women to seek elected office and shape public policy. Both the Republican and Democratic organizations created new positions for women. The political parties showcased women at their national conventions;, placed women on party committees, and created new Women’s Divisions for the purpose of integrating new women voters into the party. President Wilson established a new Women’s Bureau in the U.S. Department of Labor and appointed union organizer Mary Anderson to lead it. Anderson held the post until 1944, building the agency into a powerful advocate for female workers.

Suffrage leaders brought their new political muscle to bear on the legislative process. They lobbied for laws addressing infant mortality and women who lost their U.S. citizenship by marrying a foreign national. At the federal level, they tried, without success, to win reforms on other important issues, including the international peace movement, child labor, and lynching.

If full suffrage produced less change than suffragists had hoped and Anti-suffragists had feared, perhaps that was partly because women did not vote as a bloc and, indeed, sometimes did not vote at all. The overall turnout for women voters was lower than men’s. Critics blamed nonvoting women for shirking their civic duty, but it is also true that not all women were enfranchised by the Nineteenth Amendment. Women from some immigrant communities were far less likely to become citizens than men of the same background, and immigrants from Asia could not become citizens at all. Many Native Americans, including women, also lacked U.S. citizenship until the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Some states continued to bar Native Americans from the ballot.

Perhaps no community was subjected to more extensive disfranchisement efforts than Black women in the Jim Crow South. Black women sometimes succeeded in registering and voting, but more often they were blocked by fraud, intimidation, or violence. When disfranchised Black women asked the League of Women Voters and the National Woman’s Party to help, the main organizations of former suffragists turned them down. Alice Paul insisted that Black women’s disfranchisement was a “race issue,” not a “woman’s issue” and thus no business of the NWP. The failure of white suffragists to address the disfranchisement of southern Black women reverberated for decades to come and undercut efforts of women of both races to make progress on issues of shared concern.

Women discovered that full suffrage did not give them greater access to power. The men in political parties at the national, state, and local level paid little attention to the women and did not include them in the decision-making process except when considering issues of children or other areas seen as within the “female dominion.” Despite winning the vote, women did not have equal rights in politics, in economics, in employment, in education, or in the social sphere. They would have to continue to use innovative strategies to be heard.

Related Lessons or Education Materials

A New Home on Capitol Hill: Fighting for the Equal Rights Amendment

Lobbying for Equality: Examining the "Deadly Political Index"

Contact Information

Email us about this lesson plan