Last updated: September 1, 2020

Article

Lobbying for Suffrage

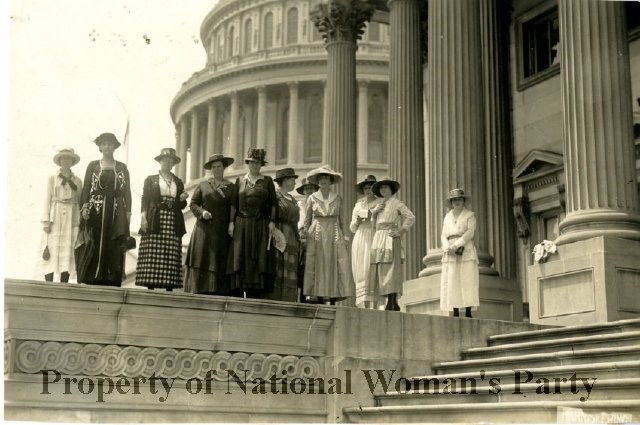

National Woman's Party

Women fighting for the right to vote faced a particularly difficult challenge. Without the power of the ballot, how would they convince politicians to support women's suffrage? They would have to develop innovative lobbying methods if they were to win lawmakers over to their cause.

A Tale of Two Mauds

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), led by Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, formed a lobbying arm called the Congressional Committee in 1910 with the purpose of raising awareness in Congress about a proposed amendment to the U.S. Constitution enfranchising women. Drafted by Susan B. Anthony, the amendment was first introduced in Congress in 1878 but after one failed vote got no further. NAWSA tended to concentrate its efforts on winning the vote one state at a time rather than on pressing for passage of the amendment. Between 1890 and 1912, women won the vote in several western states and interest in the federal amendment stalled. The Congressional Committee succeeded in arranging hearings on Capitol Hill for the amendment but accomplished little else. They rarely even spent the meager $10 that had been budgeted for their work.

At the end of 1912, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns arrived in Washington, D.C. to assume leadership of the Congressional Committee. Their first act in support of the amendment was to organize a Woman Suffrage Procession along Pennsylvania Avenue on March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson's presidential inauguration. Building on the publicity created by the procession, Paul and Burns launched a campaign of fundraising, marches, petition drives, and publicity stunts in support of the amendment. Power struggles with the national leadership soon drove Paul and Burns to break away from NAWSA. They formed a new organization, initially called the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. Later the name changed to the National Woman's Party (NWP).

The two rival suffrage associations developed their own signature lobbying tactics in support of the national amendment. Coincidentally, women named Maud led both of the efforts.

League of Women Voters (U.S.) Records, Library of Congress

Maud Wood Park and the Front Door Lobby

"Be courteous, no matter what provocation you may seem to have to be otherwise."- from "Front Door Lobby" handbook.

When Maud Wood Park moved into NAWSA’s Suffrage House in Washington, D.C. to assume leadership of the Congressional Committee, she had a lot of experience with directing suffrage organizations but knew very little about the workings of Congress. She spent many hours familiarizing herself with the procedures and culture of the legislative process. Then she set out to train her small army of volunteers in the art of lobbying. Now under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, NAWSA had a new "Winning Plan" that continued the work to win the vote in the states while also pushing for passage of the suffrage amendment in Congress.

Park's tactics included gentle persuasion through courteous but persistent advocacy. She sent women out in pairs and taught them to cultivate relationships not only with the lawmakers but also with their staff and other workers in the congressional buildings. She wrote up a list of guidelines for productive and positive interactions even with lawmakers opposed to the suffrage amendment. “Don’t do anything to close the door to the next advocate of suffrage,” she advised.

The NAWSA team earned the nickname “front door lobby.” Members of the press joked that the women were above using “backstairs” or secret, underhanded methods common among male lobbyists. Park’s team also earned positive comparisons from congressmen with the other prominent suffragist group, the National Woman’s Party, who by 1917 had begun to employ more confrontational tactics like picketing the White House.

United States Senate/Library of Congress

Maud Younger and the Deadly Political Index

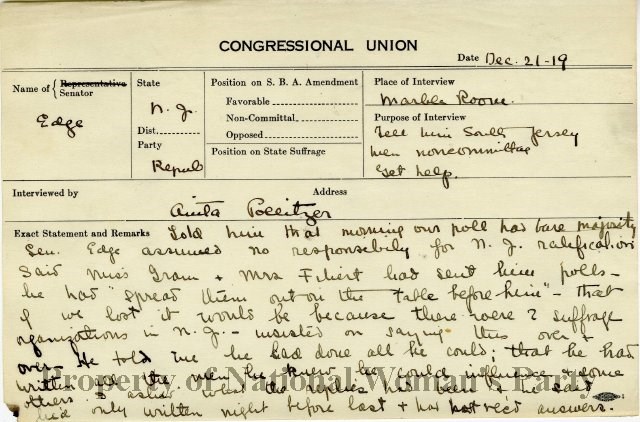

“Neither members of Congress who have swung from the anti-suffrage to the pro-suffrage column nor those who remain in the list of the antis are aware that at the headquarters of the National Woman’s Party...is a card index system so extensive in detail, political and personal, that twenty-two different cards are required for each Senator and Representative,” revealed the New York Times in March 1919. This detailed record-keeping system, which became known as the “Deadly Political Index” was overseen by San Francisco native Maud Younger.Younger grew up in a wealthy household but spent most of her life as an activist for working-class women. She joined the suffrage movement in California and then moved to Washington, D.C. at the behest of Alice Paul. She was a powerful speaker who participated in many Congressional Union and National Woman’s Party public events. In 1917, as the NWP launched its picketing campaign, Younger became the chair of the NWP’s lobbying committee. She set to work putting pressure on members of Congress to support the Susan B. Anthony amendment while the more-visible picketers focused their efforts on winning President Wilson’s endorsement.

At the heart of Younger’s lobbying strategy was the extensive card index. Her team of lobbyists recorded all the details they were able to discover about a congressional member’s background, affiliations, family members, financial supporters, and other political activity beyond his position on suffrage. They noted what newspapers he read, what clubs or lodges he belonged to, and whether or not he was a drinker. A congressman or senator who claimed that his constituents were against the amendment would find himself flooded with letters from his district or state proclaiming support. He might get a call from a prominent political donor or even his mother urging him to change position. (In 1916, Jeannette Rankin became the first woman elected to the House of Representatives, but she was an ardent supporter of the suffrage amendment so no card was required for her.)

Reporters investigating the index strategy were skeptical that the women were able to collect so much information on their own. Younger denied the suggestion that the NWP employed private detectives. “We are organized all over the country,” she explained, and had many networks for intelligence-gathering. Unlike Maud Wood Park’s NAWSA lobbyists, the NWP team were perfectly comfortable with mining the confidences of other congress members who supported suffrage. They refused to record any scandalous gossip that came their way, but the idea that the women had notes about the men’s golf partners and religious habits was a bit unnerving to many members of Congress. None who were convinced to support the amendment admitted that the Deadly Political Index was a factor. At least one representative was convinced by their extensive letter-writing campaign, though. “If you will only stop, I will vote for the amendment,” declared an unnamed congressmen quoted by the New York Times. “It keeps my office force busy all day answering letters about suffrage alone.”

National Woman's Party

Out of Congress and on to the States

Whether it was the gentle persuasion of Maud Wood Park's Front Door Lobby or the relentless pressure of Maud Younger's Deadly Political Index that did the job, the Susan B. Anthony Amendment finally passed through Congress in June 1919. Women from NAWSA and NWP brought the skills they had honed in the halls of the U.S. Capitol out to the state houses across the nation to push for ratification before the November 1920 election.Sources:

Park, Maud Wood. "Front Door Lobby," handbook. National American Woman Suffrage Association records, Library of Congress."Her Pressure on Congress: Suffrage Lobbyist's Card Index Keeps Tabs on Members' Home Influences, Financial Backers, and Even Golf Partners," New York Times, 2 Mar 1919, pg 71.

"Lobbyists," Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party collection, Library of Congress.

"The Senate Passes the Woman Suffrage Amendment," United States Senate.

Ware, Susan. Why They Marched: Untold Stories of Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2019.

"Younger, Maud, 1870-1936," National Woman's Party.

Zahniser, J. D. & Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. Oxford University Press, 2014.