| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

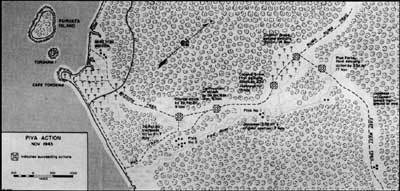

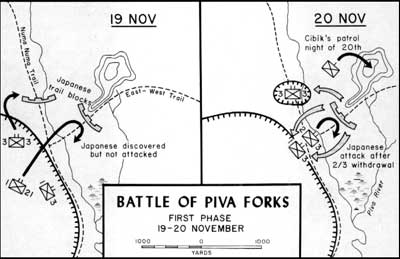

TOP OF THE LADDER: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret) Piva Forks Battle The lull after the Coconut Grove fight did not last long. On 18 November, the usual flurry of patrols soon brought back information that the Japanese had set up a road block on both the Numa-Numa Trail and the East-West Trail. To strike the Numa-Numa position, the 3d Marines sent in its 3d Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Ralph M. King), to lead the attack. It hit the Japanese flanks, routed them, and set up its own road block on 19 November. The 2d Battalion of the 3d Marines immediately went after the Japanese block on the East-West Trail between the two forks of the Piva River. After seizing that position, the next objective was a 400-foot ridge that commanded the whole area — and, in fact, provided a view all the way to Empress Augusta Bay. (As the first high ground the Marines had found, it would clearly produce a valuable observation post for directing the artillery fire of the 12th Marines.)

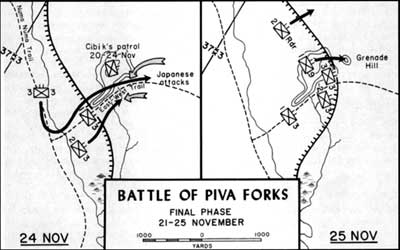

Lieutenant Colonel Hector de Zayas, commanding the battalion, summoned one of his company commanders and gave a terse order, "I want you to take it." Thus a patrol under First Lieutenant Steve J. Cibik was immediately sent to occupy it. This began a four-day epic, 20-23 November. The Marines got to the top, realized the importance of the vantage point to the Japanese, dug in defensive positions, and got ready for the enemy counterattacks that were sure to come. And they came, and came, and came. There were "fanatical attempts by the Japanese to reoccupy the position" in the form of "wild charges that sometimes carried the Japanese to within a few feet of their foxholes on the crest of the ridge." Cibik called in Marine artillery bursts within 50 yards of his men. The Marines held and were finally relieved, exhausted but proud. Cibik was awarded a Silver Star Medal, and the hill was always known there after as "Cibik Ridge." While the firestorm roared where Cibik stood, the 3d Marines were pursuing its mission of driving the Japanese from the first and nearest of Piva's forks. The 2d Battalion caught up with Cibik, and Lieutenant Colonel de Zayas moved it out down the reverse slope of Cibik Ridge. The Japanese struck hard on 21 November and de Zayas pulled back. Then, in true textbook fashion, the Japanese followed right behind him. The Marines were ready, machine guns in place. One of them killed 74 out of 75 of the enemy attackers within 20-30 yards of the gun. The 3d Marines was supported by the 9th, and 21st Marines, and the raiders, while the 37th Infantry Division provided road blocks, patrols, and flank security. Support was also provided by the Army's heavy artillery, the 12th Marines, and the defense battalions. All the troops were now be entering a new phase of the campaign, during which the fight would be more for the hills than for the trails. Reconnaissance patrols provided a good idea of what was out there, but they also discovered that the enemy was not alert as he could or should be. A Marine rifle company, for instance, came upon a clearing where the Japanese were acting as if no war was on — the troops were lounging, kibitzing, drinking beer. The Marine mortars tore them apart. Another patrol waited until the occupants of a bivouac lined up for chow before cutting them down with mortars in a pandemonium of pots, pans, and tea kettles. (Jungle combat had taught the Marines the wisdom of General Turnage's order: Marines go nowhere with out a weapon!)

The various, successive objectives for the Marine and Army riflemen were codenamed using the then-current phonetic alphabet: Dog (reached 15 November), Easy (reached 20 November, except for the 9th Marines, slowed by an impassable swamp), Fox (finally reached by the Marines on 28 November) and How (part of it reached by the Army on 23 November since it encountered "no opposition," and the remainder as a goal for the Marines). Thereafter, the Marines were to press on to the Item and Jig objectives "on orders from Corps Headquarters." One account makes clear the overwhelming difficulties facing the Marine battalions: "water slimy and often waist deep, some times to the arm pits . . . tangles of thorny vines that inflicted painful wounds men slept setting up in the water . . . sultry heat and stinking muck."

In spite of this, elaborate plans were made to continue the attack from west to east. The "strongly entrenched" Japanese defenses, with 1,200-1,500 men, were oriented to repel an assault from the south. Accordingly, the artillery observers on Cibik Ridge registered their fire on 23 November, in preparation for a thrust by two battalions of the 3d Marines to try to advance 800 yards beyond the east fork of the Piva River. All available tanks and supporting weapons were moved forward. Marine engineers from the 19th Marines joined Seabees under enemy fire in throwing bridges across the Piva River. On 23 November, as the night fell like a heavy curtain, seven battalions of artillery lined up, some almost hub-to-hub. There were the Army's 155s, 105s, mortars, 90mm AA; and the same array of the 12th Marines' cannons, plus 44 machine guns and even a few Hotchkiss pieces taken from the enemy. The attack in the morning began with the barrage at 0835, 24 November, Thanksgiving Day; a shuddering burst of flame and thunder, possibly the heaviest such barrage a Marine operation had ever before placed on a target. The shells, 5,600 rounds of them, descended on a narrow 800-foot square box of rain forest, only 100 yards from the Marines, so close that shell splinters and concussion snapped twigs off bushes around them.

Yet, as the two assault battalions moved out, the redoubtable Japanese 23d Infantry crashed in with their own heavy barrage. Their shells left Marines dead, bleeding, and some drowned in the murky Piva River, "the heaviest casualties of the campaign. Twice the enemy fire walked up and down the attacking Marines with great accuracy." But the 3d Marines came on with a juggernaut of tanks, flame throwers, and machine gun, mortar, and rifle fire. Where the Army-Marine artillery barrages fell, however, there was desolation. Major Schmuck, a company commander in one of the assault battalions, later remembered:

There was one final flourish. It had been, after all, Thanksgiving Day, and a tradition had to be observed. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had decreed that all servicemen should get turkey — one way or another. Out there on the line the men got it by "the other." Yet, few Marines of that era would give the Old Corps bad marks for hot chow. If they could get it to the frontline troops, they would. A Marine recalled, "The carrying parties did get the turkey to them. Nature won, though, the turkey had spoiled." Another man was watching the big birds imbedded in rice in five gallon containers, "much like home except for baseball and apple pie." For some, however, just before the turkey was served, the word came down, "Prepare to move out!" Those men got their turkey and ate it on the trail . . . on the way to a new engagement, Hand Grenade Hill. Before that could be assaulted, there was a reorganization on D plus 24. The beat-up 3d Marines was beefed up by the 9th Marines and the 2d Raiders. Since D-Day a total of 2,014 Japanese dead had been counted, but "total enemy casualties must have been at least three times that figure." And as a portent for the future use of Bougainville as a base for massive air strikes against the Japanese, U.S. planes were now able to use the airstrip right by the Torokina beachhead. With the enemy at last driven east of the Torokina River, Marines now occupied the high ground which controlled the site of the forthcoming Piva bomber airstrip.

|