| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

TOP OF THE LADDER: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret) The Battle for Piva Trail Captain Conrad M. Fowler, a company commander in the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, later recalled how an attack down the trails was expected: "They had to come our way to meet us face-to-face. The trails were the only way overland through that rainforest." His company would be there to meet them. He was awarded a Silver Star Medal.

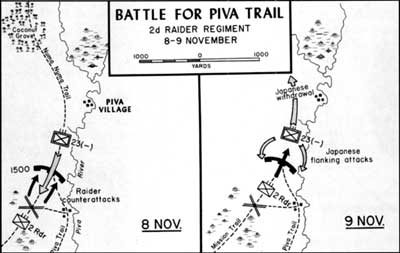

With just such a Japanese attack anticipated, General Turnage had dispatched a company of the 2d Raider Regiment up the Mission (Piva) trail on D-Day to set up a road block — just up from the old Buretoni Catholic Mission (still in operation today). At first the raiders had little business, and by 4 November elements of the 9th Marines had arrived to join them. The enemy, the 23rd Infantry up from Buin, struck on 7 November. Their attack was timed to coincide with the Koromokina landings. The raiders held, but "the woods were full of Japs, dead . . . . The most we had to do was bury them." At this point General Turnage told Colonel Edward A. Craig, commanding officer of the 9th Marines, to clear the way ahead and advance to the junction of the Piva and Numa-Numa trails. That mission Craig gave to the 2d Raider Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Alan B. Shapley. The actual attack would be led by Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, 3d Raider Battalion, just in from Puruata Island and would include elements of the 9th Marines and weapons companies. The Japanese didn't wait for a Marine attack; they came in on 5 November and threatened to overrun the trailblock. It soon became a matter of brutal small encounters, and battles raged for five days. They were many brave acts. Privates First Class Henry Gurke and Donald G. Probst, with an automatic weapon, were about to be overwhelmed. A grenade plopped in the foxhole between them. To save the critical position and his companion, Gurke thrust Probst aside and threw himself on the grenade and died. He was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously; Probst, the Silver Star Medal. Mortars and artillery dueled from each side. The Japanese would creep right next to the Marine positions for safety. Marines had to call friendly fire almost into their laps. On the narrow trail, men often had to expose themselves. The Japanese got the worst of it, for suddenly, shortly after noon on 9 November the enemy resistance crumbled. By 1500, the junction of the Piva and Numa-Numa trails was reached and secured. Some 550 Japanese died. There were 19 Marines dead and 32 wounded.

To consolidate the hard-won position, Marine torpedo bombers from Munda blasted the surrounding area on 10 November. This allowed two battalions of the 9th Marines to settle into good defensive positions along the Numa-Numa Trail with, as usual, "aggressive" patrols immediately fanning out. The battle for the Piva Trail had ended victoriously. The key logistical element in this engagement — and nearly all others on Bougainville — was the amtrac. There were vast areas where tanks and half-tracks, much less trucks, simply could not negotiate the bottomless swamps, omnipresent streams, and viscous mud from the daily rains. The amtracs proved amazingly flexible; they moved men, ammunition, rations, water, barbed wire, and even radio jeeps to the front lines where they were most needed. Heading back, they evacuated the wounded to reach the desperately needed medical centers in the rear.

Other developments came at this juncture in the campaign. As noted, the 37th Infantry Division was fed into the perimeter. At the top of the command echelon Major General Roy S. Geiger relieved Vandegrift as Commanding General, IMAC, on 9 November and took charge of Marine and Army units in the campaign from an advanced command post on Bougainville. The Seabees and Marine engineers were hard at work now. Operating dangerously 1,500 yards ahead of the front lines, guarded by a strong combat patrol, they managed to cut two 5,000—foot survey lanes east to west across the front of the perimeter.

|