| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

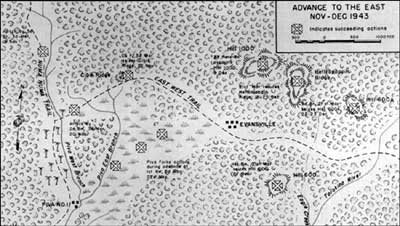

TOP OF THE LADDER: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret) Hellzapoppin Ridge Now the action shifted to the final targets of the 3d Marine Division: that mass of hills 2,000 yards away. Once captured, they would block the East-West Trail where it crossed the Torokina River, and they would greatly strengthen the Final Inland Defense Line that was the Marines' ultimate objective. A supply base, called Evansville, was built up for the attack in the rear of Hill 600 for the forthcoming attacks. The 1st Marine Parachute Regiment, under Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Williams, was informed, two days after its arrival on Bougainville, that General Turnage had assigned it to occupy those hills which IMAC felt still dominated much of the Marine ground. That ridgeline included Hill 1000 with its spur soon to be called Hellzapoppin Ridge (named after "Hellzapoppin," a long-running Broadway show), Hill 600, and Hill 600A. To take the terrain Williams got the support of elements of the 3d, 9th, and 21st Marines (which had established on 27 November its own independent outpost on Hill 600). By 5 December, the 1st Parachute Regiment had won a general outpost line that stretched from Hill 1000 to the junction of the East-West Trail and the Torokina River.

Then on 7 December, Major Robert T. Vance on Hill 1000 with his 3d Parachute Battalion walked the ridge spine to locate enemy positions on the adjacent spur that had been abandoned. The spur was fortified by nature: matted jungle for concealment, gullies to impair passage, steep slopes to discourage everything. That particular hump, which would get the apt name of Hellzapoppin Ridge, was some 280 feet high, 40 feet across at the top, and 650 feet long, and ideal position for over all defense.

Jumping off from Hill 1000 on the morning of 9 December to occupy the spur, Vance's men were hit by a fusillade of fire. The Japanese had come back, 235 of them of the 23d Infantry. The parachutists attacked again and again, without success. Artillery fire was called in, but the Japanese found protective concealment on the reverse slopes. Marine shells burst high in the banyan trees, up and away from the dug-in enemy. As a result, the parachutists were hit hard. "Ill-equipped and under strength," they were pulled back on 10 December to Hill 1000. Two battalions of the 21st Marines, with a battalion of the 9th Marines guarding their left flank, continued the attack. It would go on for six gruelling days. Scrambling up the slopes, the new attacking Marines would pass the bodies of the parachutists. John W. Yager, a first lieutenant in the 21st recalled, "The para-Marines made the first contact and had left their dead there. After a few days, they had become very unpleasant reminders of what faced us as we crawled for ward, in many instances right next to them."

Sergeant John F. Pelletier, also in the 21st, was a lead scout. Trying to cross the ridge spine over to the Hellzapoppin spur, he found dead paratroopers all over the hill. There were dead Japanese soldiers still hanging from trees, and it seemed to him that no Marine had been able to cross to the crest and live to tell about it. Pelletier described what happened next:

When artillery fire proved ineffective in battering the Japanese so deeply dug in on Hellzapoppin Ridge, Geiger called on 13 December for air attacks. Six Marine planes had just landed at the newly completed Torokina airstrip. They came in with 100-pound bombs, guided to their targets by smoke shells beyond the Marine lines. But the Japanese were close, very close. Dozens of the bombs were dropped 75 yards from the Marines. With additional planes, there were four bombing and strafing strikes over several days. A Marine on the ground never forgot the bombers roaring in right over the brush, the ridge, and the heads of the Marines to drop their load, "It seemed right on top of us." (This delivery technique was necessary to put the bombs on the reverse slope among the Japanese.) Helping to control these early strikes and achieve pinpoint accuracy was Lieutenant Colonel William K. Pottinger, G-3 (Operations Officer) of the Forward Echelon, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. He had taken a radio out of a grounded plane, moved to the frontlines, and helped control the attacking Marine planes on the spot. (This technique was an improvised forerunner of the finely tuned procedures that Marine dive bombers would use later to achieve remarkable results in close air support of ground troops.)

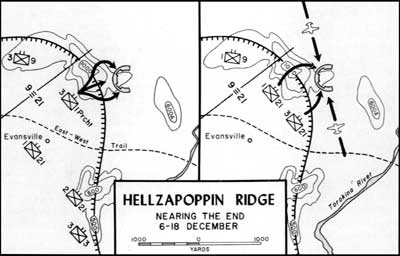

The 3d Marine Division's history was pithy in its evaluation, "It was the air attacks which proved to be the most effective factor in the taking of the ridge . . . the most successful examples of close air support thus far in the Pacific War." Geiger wasn't through. He had a battery of the Army's 155mm howitzers moved by landing craft to new firing positions near the mouth of the Torokina River. Now the artillery could pour it on the enemy positions on the reverse slopes. In one of the daily Marine assaults, one company went up the ridge for two attacks against Japanese who would jump into holes they had dug on the reverse slope to escape bombardment. The Japanese finally were tricked when another company, relieving the first one, jumped into the enemy foxholes before their rightful owners. It cost the Japanese heavily to try to return. In a final assault on 18 December, the two battalions of the 21st moved from Hill 1000 to the spur in a pincer and double envelopment. But the artillery and bombs had done their work. The Japanese and their fortress were shattered. Stunned defenders were easily eliminated. Patrick O'Sheel, a Marine combat correspondent, summed up the bitter battle, "No one knows how many Japs were killed. Some 30 bodies were found. Another dozen might have been put together from arms, legs, and torsos. The 21st suffered 12 killed and 23 wounded.

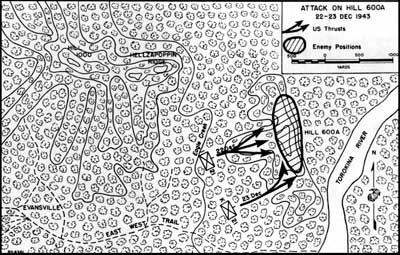

With Hellzapoppin finally behind them, Marines could count what blessings they could find and recount how rotten their holidays were. There had been a Thanksgiving Day spent on the trail while gnawing a drumstick on the way to another engagement at Piva Forks. And now, on 21 December, four days until Christmas, and the troops still had Hill 600A to "square away." Reconnaissance found 14-18 Japanese on that hill, down by the Torokina River. A combat patrol from the 21st Marines moved to drive the Japanese off the knob. It wasn't hard, but it cost the life of one Marine and one was wounded. But IMAC wanted a permanent outpost on the hill, and the 3d Battalion, 21st, drew the assignment. It began with one rifle platoon and a platoon of heavy machine guns on 22 December. Hill 600A was a repeat of past enemy tactics. The Japanese had come back to occupy it. They held against all efforts, even against a two-pronged attack. A full company came up and made three assaults. That didn't help either. Late on the 23d, the Marines held for the night, preparing to mount another attack in the morning. That morning was Christmas Eve, 1943. Scouts went up to look. The Japanese had gone. Christmas wasn't merry, but it was better. For the 3d Marine Division, the war was over on Bougainville.

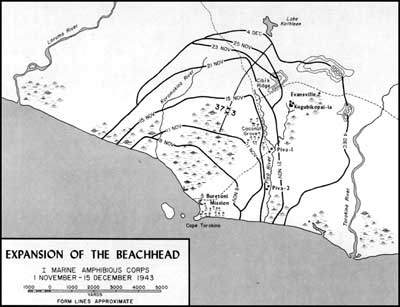

The landing force had seized the beachhead, destroyed or over come the enemy, and won the ground for the vital airfields. Now they prepared to leave, as the airfields were being readied to reduce Rabaul and its environs. Since 10 December, F4U Vought Corsairs of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 216 (1st Marine Aircraft Wing) had settled on the new strip on Torokina, almost washed by the sea. The fighter planes would be the key to the successful prosecution of the AirSols (Air Solomons) offensive against Rabaul, for, as escorts, they made large-scale bombing raids feasible. Major General Ralph J. Mitchell, USMC, had become head of AirSols on 20 November 1943. By 9 January 1944, both the fighter and bomber aircraft were operating from the Piva strips. Following Bougainville, Mitchell would have twice the airpower and facilities that the Japanese had in all of the Southwest Pacific area. The campaign had cost the Marines 423 killed and 1,418 wounded. Enemy dead were estimated at 2,458, with only 23 prisoners captured. It was now time for the 3d Marine Division to go home to Guadalcanal, with a "well done" from Halsey. (In the Admiral's colorful language, a message to Geiger said, "You have literally succeeded in setting up and opening for business a shop in the Japs' front yard.") Now there would be plenty of papayas and Lister bags, as well as a PX, a post office, and some sports and movies. General Turnage was relieved on 28 December by Major General John R. Hodge of the Americal Division, which took over the eastern sector. The 37th Infantry Division kept its responsibility for the western section of the Bougainville perimeter. Admiral Halsey directed the Commanding General, XIV Corps, Major General Oscar W. Griswold, to relieve General Geiger, Commanding General, IMAC. The Army assumed control of the beachhead as of 15 December. The 3d Marines left Bougainville on Christmas Day. The 9th left on 28 December, and had a party with two cans of beer per man. The 21st, last to arrive on the island, was the division's last rifle regiment to leave, on 9 January 1944. Every man in those regiments knew full well the crucial role that the supporting battalions had played. The 19th Marines' pioneers and engineers had labored ceaselessly to build the bridges and trails that brought the vital water, food, and ammunition to the front lines through seemingly impassable swamps, jungle, and water, water everywhere. And the amtracs of the 3d Amphibian Tractor Battalion had proven essential in getting 22,922 tons of those supplies to the rifle men. They were "the most important link in the all-important supply chain."

Working behind the amtracs were the unsung men of the 3d Service Battalion who, under the division quartermaster, Colonel William C. Hall, brought order and efficiency from the original, chaotic pile-up of supplies on the beach. As roads were slowly built, the 6x6 trucks of the 3d Motor Transport Battalion moved the supplies to advance dumps for the amtracs to pick up. The 12th Marines and Army artillery had given barrage after barrage of preparatory fire — 72,643 rounds in all. The invaluable role of Marine aviation, as previously mentioned, was symbolized by General Turnage's repeated requests for close air support, 10 strikes in all. The Seabees, working at a "feverish rate," had miraculously carved three airfields out of the unbelievable morass that characterized the area. And it was from those bases that the long-range, strategic effects of Bougainville would be felt by the enemy. The 3d Medical Battalion had taken care of the wounded. With omnipresent corpsmen on the front lines in every battle and aid stations and field hospitals right behind, the riflemen knew they had been well tended. General Turnage summarized the campaign well, "Seldom have troops experienced a more difficult combination of combat, supply, and evacuation. From its very inception, it was a bold and hazardous operation. Its success was due to the planning of all echelons and the indomitable will, courage, and devotion to duty of all members of all organizations participating." Thus it was that the capture of Bougainville marked the top of the ladder, after the long climb up the chain of the Solomon Islands.

|