| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

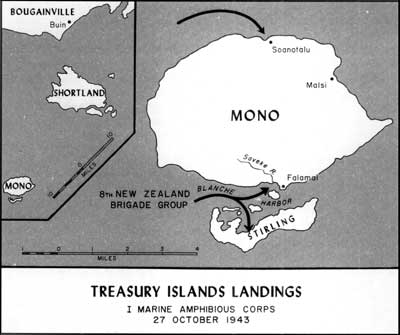

TOP OF THE LADDER: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret) Diversionary Landings There was another key element in the American plan: diversion. To mislead the enemy on the real objective, Bougainville, the IMAC operations order on 15 October directed the 8th Brigade Group of the 3d New Zealand Division to land on the Treasury Islands, 75 miles southeast of Empress Augusta Bay. There, on 27 October, the New Zealanders, under Brigadier R. A. Row, with 1,900 Marine support troops, went ashore on two small islands. One was named Mono and the other Sterling. Mono is about four miles wide, north to south, and seven miles long. It looks like a pancake. Sterling, shaped like a hook, is four miles long, narrow in places to 300 yards, but with plenty of room on its margins for airstrips.

In a drizzly overcast, the 29th NZ Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel F. L. H. Davis) and the 36th (Lieutenant Colonel K. B. McKenzie-Muirson) hit Mono at Falami Point, and the 34th (under Lieutenant Colonel R.J. Eyre) struck the beach of Sterling Island off Blanche Harbor. There was light opposition. Help for the assault troops came from LCI (landing craft, infantry) gunboats which knocked out at least one deadly Japanese 40mm twin-mount gun and a couple of enemy bunkers. A simultaneous landing was then made on the opposite or north side of Mono Island at Soanotalu. This was perhaps the most important landing of all, for there New Zealand soldiers, American Seabees, and U.S. radar specialists would set up a big long-range radar station.

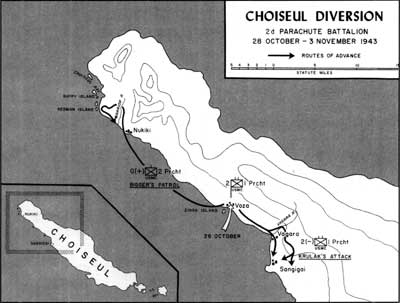

The Japanese soon reacted to the Soanotalu landing and hurled themselves against the perimeter. On one occasion, 80-90 Japanese attacked 50 New Zealanders who waited until they saw "the whites of their eyes." They killed 40 of the Japanese and dispersed the rest. There was unexpected machine gun fire at Sterling. One Seabee bulldozer operator attacked the machine gun with his big blade. An Army corporal, a medic, said he couldn't believe it, "The Seabee ran his dozer over and over the machine gun nest until everything was quiet . . . . It all began to stink after a couple of days." Outmanned, the Japanese drew back to higher ground, were hunted down, and killed. Surrender was still not in their book. On 12 November, the New Zealanders could call the Treasuries their own with the radar station in operation. Japanese dead totaled 205, and the brigade took only eight prisoners. The operation had secured the seaside flank of Bougainville, and very soon on Sterling there was an airfield. It began to operate against enemy forces on Bougainville on Christmas Day, 1943. A second diversion, east of the Treasury Islands and 45 miles from Bougainville, took place on Choiseul Island. Sub-Lieutenant C. W. Seton, Royal Australian Navy and coastwatcher on Choiseul, said the Japanese there appeared worried. The garrison troops were shooting at their own shadows, perhaps because American and Australian patrols had been criss-crossing the 80-miles-long (20-miles-wide) island since September, scouting out the Japanese positions. There were also some 3,500 transient enemy troops on Choiseul, bivouacked and waiting to be shipped the 45 miles north to Buin on Bougainville, where there was already a major Japanese garrison force. Uncertainty about the American threat of invasion somewhere was enough to make the Japanese, especially Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, Commander, Southeast Area Fleet, at Rabaul jittery. It was he who wanted much of the Japanese Seventeenth Army concentrated at Buin, for, he thought, the Allies might strike there. General Vandegrift wanted to be sure that the Japanese were focused on Buin. So, on 20 October, he called in Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Williams, commanding the 1st Parachute Regiment, and Lieutenant Colonel Victor H. Krulak, commanding its 2d Battalion. Get ashore on Choiseul, the general ordered, and stir up the biggest commotion possible, "Make sure they think the invasion has commenced. ..." It was a most unusual raid, 656 men, a handful of native guides, and an Australian coastwatcher with a road map. The Navy took Krulak's reinforced battalion of parachutists to a beach site near a hamlet called Voza. That would be the CP (command post) location for the duration. The troops slipped ashore on 28 October at 0021 and soon had all their gear concealed in the bush. By daylight, the Marines had established a base on a high jungle plateau in the Voza area. The Japanese soon spotted the intruders, sent a few fighter planes to rake the beach, but that did no harm. They did not see the four small landing craft which Krulak had brought along and hidden among some mangroves with their Navy crews on call.

Krulak then outlined two targets. Eight miles south from their CP at Voza there was a large enemy barge base near the Vagara River. The Australian said some 150 Japanese were there. The other objective was an enemy outpost in the opposite direction, 17 miles north on the Warrior River. Then Krulak took his operations officer, Major Tolson A. Smoak, 17 men, and a few natives as scouts, and headed for the barge basin. On the way, 10 unlucky Japanese were encountered unloading a barge. The Marines opened fire, killing seven of them and sinking the barge. After reconnoitering the main objective, the barge basin, the patrol returned to Voza. The following morning, Krulak sent a patrol near the barge basin to the Vagara River for security and then to wave in his small landing craft bringing up his troops to attack. But, back at Voza, along came a flight of American planes which shot up the Marines and sank one of their vital boats. Now Krulak's attack would have to walk to the village of Sangigai by the Japanese barge basin. To soften up Sangigai, Krulak called in 26 fighters escorting 12 torpedo bombers. They dropped two tons of bombs and it looked for all the world like a real invasion. Krulak then sent a company to attack the basin from the beach, and another company with rifles, machine guns, rockets, and mortars to get behind the barge center. It was a pincer and it worked. The Marines attacked at 1400 on 30 October. What the battle didn't destroy, the Marines blew up. The Japanese lost 72 dead; the Marines, 4 killed and 12 wounded. All was not so well in the other direction. Major Warner T. Bigger, Krulak's executive officer, had been sent north with 87 Marines toward the big emplacement on Choiseul Bay near the Warrior River. His mission was to destroy, first the emplacement, with Guppy Island, just off shore and fat with supplies, as his secondary target. Bigger got to the Warrior River, but his landing craft became stuck in the shallows, so he brought them to a nearby cove, hid them in the jungle, and proceeded on foot north to Choiseul Bay. Soon his scouts said that they were lost. It was late in the day so Bigger bivouacked for the night. He sent a patrol back to the Warrior where it found a Japanese force. Slipping stealthily by them, the patrol got back to Voza. This led Krulak to call for fighter cover and PT boats to try to get up and withdraw Bigger.

But Bigger didn't know he was in trouble, and he went ahead and blasted Guppy island with mortars, because he couldn't get to the main enemy emplacement. When Bigger and his men barely got back to the Warrior River, there were no rescue boats, but there were plenty of Japanese. As the men waited tensely, the rescue boats came at the last moment, the very last. Thankfully, the men scrambled on board under enemy fire. Then two PT boats arrived, gun blazing, and provided cover so Bigger's patrol could get back to Voza. One of the PT boats was commanded by Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, USN, later the President of the United States, who took 55 Marines on board when their escape boat sank. Krulak had already used up all his time and luck. The Japanese were now on top of him, their commanders particularly chagrined that they had been fooled, for the big landing had already occurred at Empress Augusta Bay. Krulak had to get out; Coastwatcher Seton said there was not much time. On the night of 3 November, three LCIs rendezvoused off Voza. Krulak gave all his rations to the natives as the Marines boarded the LCIs. They could hear their mines and booby traps exploding to delay the Japanese. Within hours after the departure, a strong Japanese pincer snapped shut around the Voza encampment, but the Marines had gone, having suffered 9 killed, 15 wounded, and 2 missing, but leaving at least 143 enemy dead on Choiseul.

|