|

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa

by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret)

Assault on Shuri

The Tenth Army's Action Report for the battle of

Okinawa paid this understated compliment to the Thirty-second

Army's defensive efforts: "The continued development and improvement

of cave warfare was the most outstanding feature of the enemy's tactics

on Okinawa." In their decision to defend the Shuri highlands across the

southern neck of the island, General Ushijima and his staff had selected

the terrain that would best dominate two of the island's strategic

features: the port of Naha to the west, and the sheltered anchorage of

Nakagusuku Bay (later Buckner Bay) to the east. As a consequence, the

Americans would have to force their way into Ushijima's preregistered

killing zones to achieve their primary objectives.

Everything about the terrain favored the defenders.

The convoluted topography of ridges, draws, and escarpments served to

compartment the battlefield into scores of small firefights, while the

general absence of dense vegetation permitted the defenders full

observation and interlocking supporting fires from intermediate

strongpoints. As at Iwo Jima, the Japanese Army fought largely from

underground positions to offset American dominance in supporting arms.

And even in the more accessible terrain, the Japanese took advantage of

the thousands of concrete, lyre-shaped Okinawan tombs to provide combat

outposts. There were blind spots in the defenses, to be sure, but

finding and exploiting them took the Americans an inordinate amount of

time and cost them dearly.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

The bitterest fighting of the campaign took place

within an extremely compressed battlefield. The linear distance from

Yonabaru on the east coast to the bridge over the Asa River above Naha

on the opposite side of the island is barely 9,000 yards. General

Buckner initially pushed south with two Army divisions abreast. By 8 May

he had doubled this commitment: two Army divisions of the XXIV Corps on

the east, two Marine divisions of IIIAC on the west. Yet each division

would fight its own desperate, costly battles against disciplined

Japanese soldiers defending elaborately fortified terrain features.

There was no easy route south.

By eschewing the amphibious flanking attack in late

April, General Buckner had fresh divisions to employ in the general

offensive towards Shuri. Thus, the 77th Division relieved the 96th in

the center, and the 1st Marine Division began relieving the 27th

Division on the west. Colonel Kenneth B. Chappell's 1st Marines entered

the lines on the last day of April and drew heavy fire from the moment

they approached. By the time the 5th Marines arrived to complete the

relief of 27th Division elements on 1 May, Japanese gunners supporting

the veteran 62d Infantry Division were pounding anything that

moved. "It's hell in there, Marine," a dispirited soldier remarked to

Private First Class Sledge as 3/5 entered the lines. "I know," replied

Sledge with false bravado, "I fought at Peleliu." But soon Sledge was

running for his life:

As we raced across an open field, Japanese shells of

all types whizzed, screamed, and roared around us with increasing

frequency. The crash and thunder of explosions was a nightmare . . . .

It was an appalling chaos. I was terribly afraid.

General del Valle assumed command of the western zone

at 1400 on 1 May and issued orders for a major attack the next morning.

That evening a staff officer brought the general a captured Japanese

map, fully annotated with American positions. With growing uneasiness,

del Valle realized his opponents already knew the 1st Marine Division

had entered the fight.

|

|

An

Okinawan civilian is flushed from a cave into which a smoke grenade had

been thrown. Many Okinawans sought the refuge of caves in which they

could hide while the tide of battle passed over them. Unfortunately, a

large number of caves were sealed when Marines suspected that they were

harboring the enemy. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 125697

|

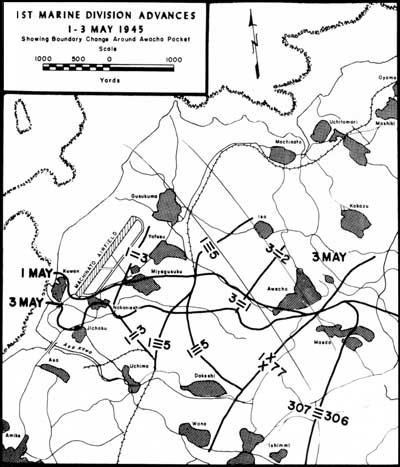

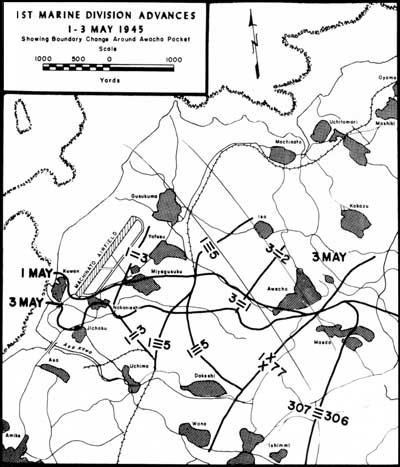

The division attacked south the next day into broken

country there after known as the Awacha Pocket. For all their combat

prowess, however, the Marines proved to be no more immune to the

unrelenting storm of shells and bullets than the soldiers they had

relieved. The disappointing day also included several harbingers of

future conditions. First, it rained hard all day. Second, as soon as the

5th Marines seized the nearest high ground they came under such intense

fire from adjacent strongpoints and from higher ground within the 77th

Division's zone to the immediate southeast they had to withdraw. Third,

the Marines spent much of the night engaged in violent hand-to-hand

fighting with scores of Japanese infiltrators. "This," said one

survivor, "is going to be a bitch."

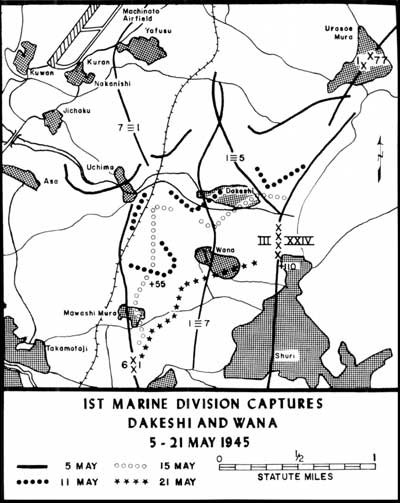

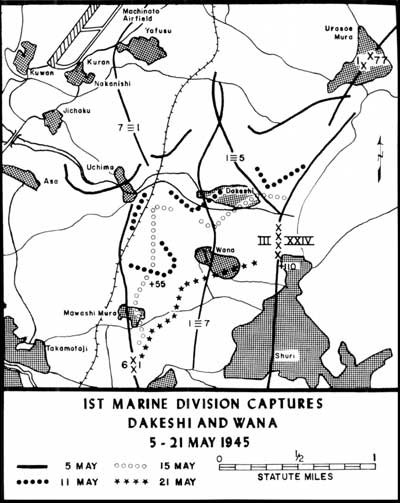

The Peleliu veterans in the ranks of the 1st Marine

Division were no strangers to cave warfare. Clearly, no other division

in the campaign could claim such a wealth of practical experience. And

while nothing on Okinawa could match the Umurbrogol's steep cliffs,

heavy vegetation, and endless array of fortified ridges, the "Old Breed"

in this battle faced a smarter, more numerous foe who had more artfully

prepared each wrinkle in the moonscape. In overcoming the sequential

barriers of Awacha, Dakeshi, and Wana, the 1st Marine Division faced

four straight weeks of hell. The funneling effects of the cliffs and

draws reduced most attacks to brutal frontal assaults by fully-exposed

tank-infantry-engineer teams. General del Valle characterized this small

unit fighting as "a slugging match with but temporary and limited

opportunity to maneuver."

|

|

A

"Ronson" tank, mounting a flame thrower, lays down a stream of fire

against a position located in one of the many Okinawan tombs set in the

island's hillsides. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 122153

|

General Buckner captured the fancy of the media with

his metaphor about the "blowtorch and corkscrew" tactics needed for

effective cave warfare, but this was simply stating the obvious to the

Army veterans of Biak and the Marine veterans of Peleliu and Iwo Jima.

Flamethrowers were represented by the blow torch, demolitions, by the

cork screw — but both weapons had to be delivered from close range

by tanks and the exposed riflemen covering them.

On 3 May the rains slowed and the 5th Marines resumed

its assault, this time taking and holding the first tier of key terrain

in the Awacha Pocket. But the systematic reduction of this strongpoint

would take another full week of extremely heavy fighting. Fire support

proved excellent. Now it was the Army's time to return the favor of

interservice artillery support. In this case, the 27th Division's field

artillery regiment stayed on the lines, and with its forward observers

and linemen intimately familiar with the terrain in that sector,

rendered yeoman service.

|

Marine Artillery at Okinawa

The nature of the enemy defenses and the tactics

selected by the Tenth Army commander made Okinawa the biggest battle of

the war for Marine artillery units. General Geiger landed with 14 firing

battalions within IIIAC; the total rose to 15 in June when Lieutenant

Colonel Richard G. Weede's 2/10 came ashore in support of the 8th

Marines.

Brigadier General David R. Nimmer commanded III Corps

Artillery, and Lieutenant Colonel Curtis Burton, Jr., commanded the 2d

Provisional Field Artillery Group, which contained three batteries of

155mm howitzers and three of 155mm "Long Tom" guns. Colonel Wilburt S.

("Big Foot") Brown commanded the 11th Marines and Colonel Robert B.

Luckey, the 15th Marines. The Marine divisions had greatly enhanced

their firepower since the initial campaigns in the Pacific. While one

75mm pack howitzer battalion remained (1/11), the 105mm howitzer had

become the norm for division artillery. Front-line infantry units also

were supported by the 75mm fire of medium tanks and LVT-As, 105mm fire

from the new M-7 self-propelled "siege guns," 4.5-inch multiple rocket

launchers fired by the "Buck Rogers Men," and the attached Army 4.2-inch

mortar platoons.

Lieutenant Colonel Frederick R. Henderson described

this combination of fire support: "Not many people realize that the

artillery in Tenth Army, plus the LVT-As and naval gun fire equivalent

gave us a guns/mile of front ratio on Okinawa that was probably higher

than any U.S. effort in World War II."

General Buckner urged his corps commanders to

integrate field artillery support early in the campaign. With his corps

artillery and the 11th Marines not fully committed during the opening

weeks, General Geiger quickly agreed for these units to help the XXIV

Army Corps in their initial assaults against the outer Shuri defenses.

In the period of 7 April-6 May, these artillery units fired more than

54,000 rounds in support of XXIV Corps. This was only the beginning.

Once both Marine divisions of IIIAC entered the lines, they immediately

benefited from Army artillery support as well as their own organic fire

support. As one example, prior to the 5th Marines launching a morning

attack on the Awacha Pocket on 6 May, the regiment received a

preliminary bombardment of the objective from four battalions — two

Army, two Marine.

By the end of the battle, the Tenth Army artillery

units would fire 2,046,930 rounds down range, all in addition to 707,500

rockets, mortars, and shells of five-inch or larger from naval gunfire

ships offshore. Half of the artillery rounds would be 105mm shells from

howitzers and the M-7 self-propelled guns. Compared to the bigger guns,

the old, expeditionary 75mm pack howitzers of 1/11 were the "Tiny Tims"

of the battlefield. Their versatility and relative mobility, however,

proved to be assets in the long haul. Colonel Brown augmented the

battalion with LVT-As, which fired similar ammunition. According to

Brown, "75mm ammo was plentiful, as contrasted with the heavier

calibers, so 1/11 (Reinforced) was used to fire interdiction, harassing,

and 'appeasement' missions across the front."

Generals Geiger and del Valle expressed interest in

the larger weapons of the Army. Geiger particularly admired the Army's

eight-inch howitzer, whose 200-pound shell possessed much more

penetrating and destroying power than the 95-pound shell of the 155mm

guns, the largest weapon in the Marines' inventory. Geiger recommended

that the Marine Corps form eight-inch howitzer battalions for the

forthcoming attack on of Japan. For his part, del Valle prized the

accuracy, range, and power of the Army's 4.2-inch mortars and

recommended their inclusion in the Marine division.

|

|

Department of

Defense Photo (USMC) 12446

|

On some occasions, artillery commanders became

tempted to orchestrate all of this killing power in one mighty

concentration. "Time on target" (TOT) missions occurred frequently in

the early weeks, but their high consumption rate proved disadvantageous.

Late in the campaign Colonel Brown decided to originate a gargantuan TOT

by 22 battalions on Japanese positions in the southern Okinawan town of

Makabe. The sudden concentration worked beautifully, he recalled, but "I

neglected to tell the generals, woke everyone out of a sound sleep, and

caught hell from all sides."

General Geiger insisted that his LVT-As be trained in

advance as field artillery. This was done, but the opportunity for

direct fire support to the assault waves fizzled on L-Day when the

Japanese chose not to defend the Hagushi beaches. Lieutenant Colonel

Louis Metzger commanded the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion and

supported the 6th Marine Division up and down the length of the island.

Metzger's LVT-As fired 19,000 rounds of 75mm shells in an artillery

support role after L-Day.

The Marines made great strides towards refining

supporting arms coordination during the battle for Okinawa. Commanders

established Target Information Centers (TICs) at every level from Tenth

Army down to battalion. The TICs functioned to provide a centralized

target information and weapons assignment system responsive to both

assigned targets and targets of opportunity. Finally, all three

component liaison officers — artillery, air, and naval gunfire

— were aligned with target intelligence information officers. As

described by Colonel Henderson, the TIC at IIIAC consisted of the corps

artillery S-2 section "expanded to meet the needs of artillery, NGF, and

CAS on a 24-hour basis . . . . The Corps Arty Fire Direction Center and

the Corps Fire Support Operations Center were one and the same facility

— with NGF and air added."

Such a commitment to innovation led to greatly

improved support to the foot-slogging infantry. As one rifle battalion

commander remarked, "It was not uncommon for a battleship, tanks,

artillery, and aircraft to be supporting the efforts of a platoon of

infantry during the reduction of the Shuri position."

|

At this point an odd thing happened, an almost

predictable chink in the Japanese defensive discipline. The genial

General Ushijima permitted full discourse from his staff regarding

tactical courses of action. Typically, these debates occurred between

the impetuous chief of staff, Lieutenant General Isamu Cho, and the

conservative operations officer, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara. To this

point, Yahara's strategy of a protracted holding action had prevailed.

The Thirty-second Army had resisted the enormous American

invasion successfully for more than a month. The army, still intact,

could continue to inflict high casualties on the enemy for months to

come, fulfilling its mission of bleeding the ground forces while the

"Divine Wind" wreaked havoc on the fleet. But maintaining a sustained

defense was anathema to a warrior like Cho, and he argued stridently for

a massive counterattack. Against Yahara's protests, Ushijima sided with

his chief of staff.

|

|

Marines of the 1st Division move carefully toward the

crest of a hill on their way to Dakeshi. The forwardmost Marines stay

low, off of the skyline. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

120412

|

The greatest Japanese counterattack of 4-5 May proved

ill-advised and exorbitant. To man the assault forces, Ushijima had to

forfeit his coverage of the Minatoga sector and bring those troops

forward into unfamiliar territory. To provide the massing of fires

necessary to cover the assault he had to bring most of his artillery

pieces and mortars out into the open. And his concept of using the

26th Shipping Engineer Regiment and other special assault forces

in a frontal attack, and, at the same time, a waterborne, double

envelopment would alert the Americans to the general counteroffensive.

Yahara cringed in despair.

|

|

In

the end, victory was achieved at Okinawa by well-trained assault troops

on the ground, like this Marine flamethrower operator and his watchful

rifleman. Marine Corps Historical Center

|

The events of 4-5 May proved the extent of Cho's

folly. Navy "Flycatcher patrols on both coasts interdicted the first

flanking attacks conducted by Japanese raiders in slow-moving barges and

native canoes. Near Kusan, on the west coast, the 1st Battalion, 1st

Marines, and the LVT-As of the 3d Armored Amphibian Battalion greeted

the invaders trying to come ashore with a deadly fire, killing 700.

Further along the coast, 2/1 intercepted and killed 75 more, while the

1st Reconnaissance Company and the war dog platoon tracked down the last

65 hiding in the brush. Meanwhile the XXIV Corps received the brunt of

the overland thrust and contained it effectively, scattering the

attackers into small groups, hunting them down ruthlessly. The 1st

Marine Division, instead of being surrounded and annihilated in

accordance with the Japanese plan, launched its own attack instead,

advancing several hundred yards. The Thirty-second Army lost more

than 6,000 first-line troops and 59 pieces of artillery in the futile

counterattack. Ushijima, in tears, promised Yahara he would never again

disregard his advice. Yahara, the only senior officer to survive the

battle, described the disaster as "the decisive action of the

campaign."

|

|

Men

of the 7th Marines wait until the exploding white phosphorous shells

throw up a thick-enough smoke screen to enable them to advance in their

drive towards Shuri. The smoke often concealed the relentlessly

attacking troops. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 120182

|

At this point General Buckner decided to make it a

four-division front and ordered General Geiger to redeploy the 6th

Marine Division south from the Motobu Peninsula. General Shepherd

quickly asked Geiger to assign his division to the seaward flank to

continue the benefit of direct naval gunfire support. "My G-3, Brute

Krulak, was a naval gun fire expert," Shepherd said, noting the

division's favorable experience with fleet support throughout the

northern campaign. Unspoken was an additional benefit: Shepherd would

have only one adjacent unit with which to coordinate fire and maneuver,

and a good one at that, the veteran 1st Marine Division.

On the morning of 7 May General Geiger regained

control of the 1st Marine Division and his Corps Artillery from XXIV

Corps and established his forward CP. The next day the 22d Marines

relieved the 7th Marines in the lines north of the Asa River. The 1st

Marine Division, which had suffered more than 1,400 casualties in its

first six days on the lines while trying to cover a very wide front,

adjusted its boundaries gratefully to make room for the newcomers.

|

|

Heading south toward Shuri Castle, a 1st Marine Division

patrol passes through a small village which had been unsuccessfully

defended by Japanese troops. Department or Defense Photo (USMC)

119485

|

Yet the going got no easier, even with two full

Marine divisions now shoulder-to-shoulder in the west. Heavy rains and

fierce fire greeted the 6th Marine Division as its regiments entered the

Shuri lines. The situation remained as grim and deadly all along the

front. On 9 May, 1/1 made a spirited attack on Hill 60 but lost its

commander, Lieutenant Colonel James C. Murray, Jr., to a sniper. Nearby

that night, 1/5 engaged in desperate hand-to-hand fighting with a force

of 60 Japanese soldiers who appeared like phantoms out of the rocks.

The heavy rains caused problems for the 22d Marines

in its efforts to cross the Asa River. The 6th Engineers fabricated a

narrow foot bridge under intermittent fire one night. Hundreds of

infantry raced across before two Japanese soldiers wearing satchel

charges strapped to their chests dashed into the stream and blew

themselves and the bridge to kingdom come. The engineers then spent the

next night building a more substantial Bailey Bridge. Across it poured

reinforcements and vehicles, but the tanks played hell traversing the

soft mud along both banks — each attempt was an adventure. Yet the

22d Marines were now south of the river in force, an encouraging bit of

progress on an otherwise stalemated front.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

The 5th Marines finally fought clear of the devilish

Awacha Pocket on the 10th, ending a week of frustration and point-blank

casualties. Now it became the turn of the 7th Marines to engage its own

nightmare terrain. Due south of their position lay Dakeshi Ridge.

Coincidentally, General Buckner prodded his commanders on the 11th,

announcing a renewed general offensive along the entire front. This

proclamation may well have been in response to the growing criticism

Buckner had been receiving from the Navy and some of the media for his

time-consuming attrition strategy. But the riflemen's war had progressed

beyond high-level exhortation. The assault troops knew fully what to

expect — and what it would likely cost.

|

Marine Tanks at Okinawa

The Sherman M-4 medium tank employed by the seven

Army and Marine Corps tank battalions on Okinawa would prove to be a

decisive weapon — but only when closely coordinated with

accompanying infantry. The Japanese intended to separate the two

components by fire and audacity. "The enemy's strength lies in his

tanks," declared Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima before the

invasion. Anti-tank training received the highest priority within his

Thirty-second Army. These urgent preparations proved successful

on 19 April when the Japanese knocked out 22 of 30 Sherman tanks of the

27th Division, many by suicide demolitionists.

The Marines fared better in this regard, having

learned in earlier campaigns to integrate infantry and artillery as a

close, protective overwatch to their accompanying tanks, keeping the

"human bullet" suicide squads at bay. Although enemy guns and mines

took their tool of the Shermans, only a single Marine tank sustained

damage from a Japanese suicide foray.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J. Stuart commanded the 1st

Tank Battalion during the Okinawa campaign. The unit had fought with

distinction at Peleliu a half-year earlier, despite shipping shortfalls

which kept a third of its tanks out of the fight. Stuart insisted on

retaining the battalion's older M-4A2 Shermans because he believed the

twin General Motors diesel engines were safer in combat. General del

Valle agreed: "The tanks were not so easily set on fire and blown up

under enemy fire."

By contrast, Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Denig's 6th

Tank Battalion preferred the newer M-4A3 model Shermans. Denig's tankers

liked the greater horsepower provided by the water-cooled Ford V-8

engine and considered the reversion to gasoline from diesel an

acceptable risk. The 6th Tank Battalion would face its greatest

challenge against Admiral Minoru Ota's mines and naval guns on Oroku

Peninsula.

The Sherman tank, much maligned in the European

theater for its shortcomings against the heavier German Tigers, seemed

ideal for island fighting in the Pacific. By Okinawa, however, the

Sherman's limitations became evident. The 75mm gun proved too light

against some of Ushijima's fortifications; on these occasions the new

M-7 self-propelled 105mm gun worked better. And the Sherman was never

known for its armor protection. At 33 tons, its strength lay more in

mobility and reliability. But as Japanese anti-tank weapons and mines

reached the height of lethality at Okinawa, the Sherman's thin-skinned

weak points (1.5-inch armor on the sides and rear, for example) became a

cause for concern. Marine tank crews had resorted to sheathing the sides

of their vehicles with lumber as a foil to hand-lobbed Japanese magnetic

mines as early as the Marshalls campaign. By the time of Okinawa,

Marine Shermans were festooned with spot-welded track blocks, wire mesh,

sandbags, and clusters of large nails — all designed to enhance

armor protection.

|

|

Department of

Defense Photo (USMC) 123166

|

Both tank battalions fielded Shermans configured with

dozer blades, invaluable assets in the cave fighting to come, but —

surprisingly — neither outfit deployed with flame tanks. Despite

rave reports of the success of the USN Mark I turret-mounted flame

system installed in eight Shermans in the battle of Iwo Jima, there

would be no massive retrofit program for the Okinawa-bound Marine tank

units. Instead, all flame tanks on Okinawa were provided courtesy of

the U.S. Army's 713th Armored Flamethrower Battalion. Company B of that

unit supported the IIIAC, with brand-new H-1 flame tanks. Each carried

290 gallons of napalm-thickened fuel, good for two-and-a-half minutes of

flame at ranges out to 80 yards. The Marines received consistently

outstanding support from this Army company throughout the battle.

The Marines employed the newly developed T-6 "Tank

Flotation Devices" to get the initial assault waves of Shermans ashore

on L-Day. The T-6 featured a series of flotation tanks welded all

around the hull, a provisional steering device making use of the tracks,

and electric bilge pumps. Once ashore, the crew hoped to jettison the

ungainly rig with built-in explosive charges, a scary proposition.

The invasion landing on 1 April for the 1st Tank

Battalion was truly "April Fools Day." The captain of an LST carrying

six Shermans equipped with the T-6 launched the vehicles an hour late

and 10 miles at sea. It took this irate contingent five hours to reach

the beach, losing two vehicles on the reef at ebb tide. Most of Colonel

Stuart's other Shermans made it ashore before noon, but some of his

reserves could not cross the reef for 48 hours. The 6th Tank Battalion

had better luck. Their LST skippers launched the T-6 tanks on time and

in close. Two tanks were lost — one sank when its main engine

failed, another broke a track and veered into an unseen hole — but

the other Shermans surged ashore, detonated their float tanks

successfully, and were ready to roll by H plus 29.

Japanese gunners and mine warfare experts knocked out

51 Marine Corps Shermans in the battle. Many more tanks sustained

damage in the fighting but were recovered and restored by hard-working

maintenance crews, the unsung heroes. As a result of their ingenuity,

the assault infantry battalions never lacked for armored firepower,

mobility, and shock action. The concept of Marine combined-arms task

forces was now well underway.

|

|