| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) Closing the Loop The more open country in the south gave General del Valle the opportunity to further refine the deployment of his tank-infantry teams. No unit in the Tenth Army surpassed the 1st Marine Division's synchronization of these two supporting arms. Using tactical lessons painfully learned at Peleliu, the division never allowed its tanks to range beyond direct support of the accompanying infantry and artillery forward observers. As a result, the 1st Tank Battalion was the only armored unit in the battle not to lose a tank to Japanese suicide squads — even during the swirling close quarters frays within Wana Draw. General del Valle, the consummate artilleryman, valued his attached Army 4.2-inch mortar battery. "The 4.2s were invaluable on Okinawa," he said, "and that's why my tanks had such good luck." But good luck reflected a great deal of application. "We developed the tank-infantry team to a fare-thee-well in those swales — backed up by our 4.2-inch mortars." Colonel "Big Foot" Brown of the 11th Marines took this coordination several steps further as the campaign dragged along:

Lieutenant Colonel James C. Magee's 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, used similar tactics in a bloody but successful day-long assault on Hill 69 west of Ozato on 10 June. Magee lost three tanks to Japanese artillery fire in the approach. but took the hill and held it throughout the inevitable counterattack that night. Beyond Hill 69 loomed Kunishi Ridge for the 1st Marine Division, a steep, coral escarpment which totally dominated the surrounding grass lands and rice paddies. Kunishi was much higher and longer than Sugar Loaf, equally honeycombed with enemy caves and tunnels, and while it lacked the nearby equivalents of Half Moon and Horseshoe to the rear flanks, it was amply covered from behind by Mezado Ridge 500 yards further south. Remnants of the veteran 32d Infantry Regiment infested and defended Kunishi's many hidden bunkers. These were the last of Ushijima's organized, front-line troops, and they would render Kunishi Ridge as deadly a killing ground as the Marines would ever face.

Japanese gunners readily repulsed the first tank-infantry assaults by the 7th Marines on 11 June. Colonel Snedeker looked for another way. "I came to the realization that with the losses my battalions suffered in experienced leadership we would never be able to capture (Kunishi Ridge) in daytime. I thought a night attack might be successful." Snedeker flew over the objective in an observation aircraft, formulating his plan. Night assaults by elements of the Tenth Army were extremely rare in this campaign — especially Snedeker's ambitious plan of employing two battalions. General del Valle voiced his approval. At 0330 the next morning, Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley's 1/7 and Lieutenant Colonel Spencer S. Berger's 2/7 departed the combat outpost line for the dark ridge. By 0500 the lead companies of both battalions swarmed over the crest, surprising several groups of Japanese calmly cooking breakfast. Then came the fight to stay on the ridge and expand the toehold. With daylight, Japanese gunners continued to pole-ax any relief columns of infantry, while those Marines clinging to the crest endured showers of grenades and mortar rounds. As General del Valle put it, "The situation was one of the tactical oddities of this peculiar warfare. We were on the ridge. The Japs were in it, on both the forward and reverse slopes."

The Marines on Kunishi critically needed reinforcements and resupplies; their growing number of wounded needed evacuation. Only the Sherman medium tank had the bulk and mobility to provide relief. The next several days marked the finest achievements of the 1st Tank Battalion, even at the loss of 21 of its Shermans to enemy fire. By removing two crewmen, the tankers could stuff six replacement riflemen inside each vehicle. Personnel exchanges once atop the hill were another matter. No one could stand erect without getting shot, so all "transactions" had to take place via the escape hatch in the bottom of the tank's hull. These scenes then became commonplace: a tank would lurch into the beleaguered Marine positions on Kunishi, remain buttoned up while the replacement troops slithered out of the escape hatch carrying ammo, rations, plasma, and water; then other Marines would crawl under, dragging their wound ed comrades on ponchos and manhandle them into the small hole. For those badly wounded who lacked this flexibility, the only option was the dubious privilege of riding back down to safety while lashed to a stretcher topside behind the turret. Tank drivers frequently sought to provide maximum protection to their exposed stretcher cases by backing down the entire 800-yard gauntlet. In this painstaking fashion the tankers managed to deliver 50 fresh troops and evacuate 35 wounded men the day following the 7th Marines' night attack. Encouraged by these results, General del Valle ordered Colonel Mason to conduct a similar night assault on the 1st Marines' sector of Kunishi Ridge. This mission went to 2/1, who accomplished it smartly the night of 13-14 June despite inadvertent lapses of illumination fire by forgetful supporting arms. Again the Japanese, furious at being surprised, swarmed out of their bunkers in counterattack. Losses mounted rapidly in Lieutenant Colonel Magee's ranks. One company lost six of its seven officers that morning. Again the 1st Tank Battalion came to the rescue, delivering reinforcements and evacuating 110 casualties by dusk. General del Valle expressed great pleasure in the success of these series of attacks. "The Japs were so damned surprised," he remarked, adding, "They used to counterattack at night all the time, but they never felt we'd have the audacity to go and do it to them." Colonel Yahara admitted during his interrogation that these unexpected night attacks were "particularly effective," catching the Japanese forces "both physically and psychologically off-guard." By 15 June the 1st Marines had been in the division line for 12 straight days and sustained 500 casualties. The 5th Marines relieved it, including an intricate night-time relief of lines by 2/5 of 2/1 on 15-16 June. The 1st Marines, back in the relative safety of division reserve, received this mindless regimental rejoinder the next day: "When not otherwise occupied you will bury Jap dead in your area." The battle for Kunishi Ridge continued. On 17 June the 5th Marines assigned K/3/5 to support 2/5 on Kunishi. Private First Class Sledge approached the embattled escarpment with dread: "Its crest looked so much like Bloody Nose that my knees nearly buckled. I felt as though I were on Peleliu and had it all to go through again." The fighting along the crest and its reverse slope took place at point-blank range — too close even for Sledge's 60mm mortars. His crew then served as stretcher bearers, extremely hazardous duty. Half his company became casualties in the next 22 hours.

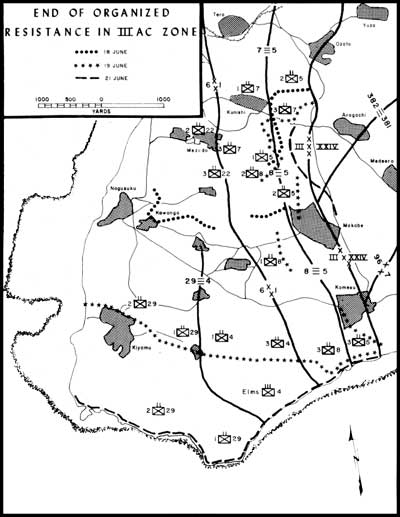

Extracting wounded Marines from Kunishi remained a hair-raising feat. But the seriously wounded faced another half-day of evacuation by field ambulance over bad roads subject to interdictive fire. Then the aviators stepped in with a bright idea. Engineers cleared a rough landing strip suitable for the ubiquitous "Grasshopper" observation aircraft north of Itoman. Hospital corpsmen began delivering some of the casualties from the Kunishi and Hill 69 battles to this improbable airfield. There they were tenderly inserted into the waiting Piper Cubs and flown back to field hospitals in the rear, an eight-minute flight. This was the dawn of tactical air medevacs which would save so many lives in subsequent Asian wars. In 11 days, the dauntless pilots of Marine Observation Squadrons (VMO) -3 and -7 flew out 641 casualties from the Itoman strip. The 6th Marine Division joined the southern battlefield from its forcible seizure of the Oroku Peninsula. Colonel Roberts' 22d Marines became the fourth USMC regiment to engage in the fighting for Kunishi. The 32d Infantry Regiment died hard, but soon the combined forces of IIIAC had swept south, over lapped Mezado Ridge, and could smell the sea along the south coast. Near Ara Saki, George Company, 2/22, raised the 6th Marine Division colors on the island's southernmost point, just as they had done in April at Hedo Misaki in the farthest north. The long-neglected 2d Marine Division finally got a meaningful role for at least one of its major components in the closing weeks of the campaign. Colonel Clarence R. Wallace and his 8th Marines arrived from Saipan, initially to capture two outlying islands, Iheya Shima and Aguni Shima, to provide more early warning radar sites against the kamikazes. Wallace in fact commanded a sizable force, virtually a brigade, including the attached 2d Battalion, 10th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Richard G. Weede) and the 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion (Major Fenlon A. Durand). General Geiger assigned the 8th Marines to the 1st Marine Division, and by 18 June they had relieved the 7th Marines and were sweeping southeastward with vigor. Private First Class Sledge recalled their appearance on the battlefield: "We scrutinized the men of the 8th Marines with that hard professional stare of old salts sizing up another outfit. Everything we saw brought forth remarks of approval." General Buckner also took an interest in observing the first combat deployment of the 8th Marines. Months earlier he had been favorably impressed with Colonel Wallace's outfit during an inspection visit to Saipan. Buckner went to a forward observation post on 18 June, watching the 8th Marines advance along the valley floor. Japanese gunners on the opposite ridge saw the official party and opened up. Shells struck the nearby coral outcrop, driving a lethal splinter into the general's chest. He died in 10 minutes, one of the few senior U.S. officers to be killed in action throughout World War II.

As previously arranged, General Roy Geiger assumed command; his third star became effective immediately. The Tenth Army remained in capable hands. Geiger became the only Marine — and the only aviator of any service — to command a field army. The soldiers on Okinawa had no qualms about this. Senior Army echelons elsewhere did. Army General Joseph Stillwell received urgent orders to Okinawa. Five days later he relieved Geiger, but by then the battle was over. The Marines also lost a good commander on the 18th when a Japanese sniper killed Colonel Harold C. Roberts, CO of the 22d Marines, who had earned a Navy Cross serving as a Navy corpsman with Marines in World War I. General Shepherd had cautioned Roberts the previous evening about his propensity of "commanding from the front." "I told him the end is in sight," said Shepherd, "for God's sake don't expose yourself unnecessarily." Lieutenant Colonel August C. Larson took over the 22d Marines.

When news of Buckner's death reached the headquarters of the Thirty-second Army in its cliff-side cave near Mabuni, the staff officers rejoiced. But General Ushijima maintained silence. He had respected Buckner's distinguished military ancestry and was appreciative of the fact that both opposing commanders had once commanded their respective service academies, Ushijima at Zama, Buckner at West Point. Ushijima could also see his own end fast approaching. Indeed, the XXIV Corps' 7th and 96th Divisions were now bearing down inexorably on the Japanese command post. On 21 June Generals Ushijima and Cho ordered Colonel Yahara and others to save themselves in order "to tell the army's story to headquarters," then conducted ritual suicide.

General Geiger announced the end of organized resistance on Okinawa the same day. True to form, a final kikusui attack struck the fleet that night and sharp fighting broke out on the 22d. Undeterred, Geiger broke out the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing band and ran up the American flag at Tenth Army headquarters. The long battle had finally run its course.

|