| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) Countdown to 'Love-Day' The Marine divisions preparing to assault Okinawa experienced yet another organizational change, the fourth of the war. Headquarters Marine Corps (HQMC), constantly reviewing the lessons learned in the war to date, had just completed a series of revisions to the tables of organization and equipment for the division and its components. Although the "G-Series" T/O would not become official until a month after the landing, the divisions had already complied with most of the changes. The overall size of each division increased from 17,465 to 19,176. This growth reflected the addition of an assault signal company, a rocket platoon (the "Buck Rogers Men"), a war dog platoon, and — significantly — a 55-man assault platoon in each regimental headquarters. Artillery, motor transport, and service units received slight increases. So did the machine gun platoons in each rifle company. The most timely weapons change occurred with the replacement of the 75mm "half-tracks" with the newly developed M-7 105mm self-propelled howitzer — four to each regiment. Purists in the artillery regiments tended to sniff at these weapons, deployed by the infantry not as massed howitzers but rather as direct-fire, open-sights "siege guns" against Okinawa's thousands of fortified caves, but the riflemen soon swore by them. Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, backed up these last-minute changes by providing the quantities of replacements required, so that each assault division actually landed at full tables of organization (T/O) strength, plus the equivalent of two replacement drafts each. Sometimes the skills required did not match the requirement, however. Some of the artillery regiments had to absorb a flood of radar technicians and antiaircraft artillery gunners from the old Defense Battalions at the last moment. But by and large, the manpower and equipment shortfalls which had beset many early operations had been overcome by the time of embarkation for the Okinawa campaign.

Surprisingly for this late in the war, operational intelligence proved less than satisfactory prior to the Okinawa landing. Where pre-assault combat intelligence had been superb in the earlier operations at Tarawa (the apogean neap tide notwithstanding) and Tinian, here at Okinawa, the landing force did not have accurate figures of the enemy's numbers, weapons, and disposition, or intelligence of his abilities. Part of the problem lay in the fact that cloud cover over the island most of the time prevented accurate and complete photo-reconnaisance of the target area. In addition, the incredible digging skills of the defending garrison and the ingenuity of the Japanese commander conspired to disguise the island's defenses.

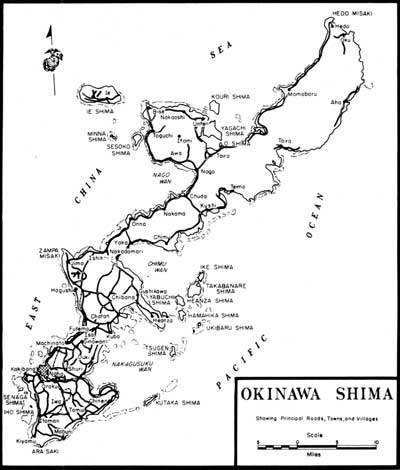

The island of Okinawa is 60 miles long, but only the lower third contained the significant military objectives of airfields, ports, and anchorages. When Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima assumed command of the Thirty-second Army in August 1944, he quickly realized this and decided to concentrate his forces in the south. He also decided, regretfully, to refrain from contesting the likely American landings along the broad beaches at Hagushi on the southwest coast. Doing so would forfeit the prize airfields of Yontan and Kadena, but it would permit Ushijima to conserve his forces and fight the only kind of battle he thought had a chance for the Empire: a defense in depth, largely underground and thus protected from the overwhelming American superiority in supporting arms. This was the attrition/cave warfare of the more recent defenses at Biak, Peleliu, and Iwo Jima. Each had exacted a frightful cost on the American invaders. Ushijima sought to duplicate this philosophy in spades. He would go to ground, sting the Americans with major-caliber gunfire from his freshly excavated "fire-port" caves, bleed them badly, bog down their momentum — and in so doing provide the Imperial Army and Navy air arms the opportunity to destroy the Fifth Fleet by massed kamikaze attacks. To achieve this strategy, Ushijima had upwards of 100,000 troops on the island, including a generous number of Okinawan conscripts, the Home Guard known as Boeitai. He also had a disproportionate number of artillery and heavy weapon units in his command. The Americans in the Pacific would not encounter a more formidable concentration of 150mm howitzers, 120mm mortars, 320mm mortars, and 47mm antitank guns. Finally, Ushijima also had time. The American strategic decisions to assault the Philippines, Peleliu, and Iwo Jima before Okinawa gave the Japanese garrison on Okinawa seven months to develop its defenses around the Shuri epicenter. Americans had already seen what the Japanese could do in terms of fortifying a position within an incredibly short time. At Okinawa, they achieved a masterpiece. Working entirely with hand tools — there was not a single bulldozer on the island — the garrison dug miles of underground fighting positions, literally honey-combing southern Okinawa's ridges and draws, and stocked each successive position with reserves of ammunition, food, water, and medical supplies. The Americans expected a ferocious defense of the Hagushi beaches and the airfields just beyond, followed by a general counterattack — then the battle would be over except for mop-up patrolling. They could not have been more misinformed. The U.S. plan of attack called for advance seizure of the Kerama Retto Islands off the southwest coast, several days of preliminary air and naval gunfire bombardment, a massive four-division assault over the Hagushi Beaches (the Marines of III AC on the north, the soldiers of XXIV Corps on the south). Meanwhile, the 2d Marine Division with a separate naval task unit would endeavor to duplicate opposite the Minatoga Beaches on Okinawa's southeast coast its successful amphibious feint off Tinian. Love-Day (selected from the existing phonetic alphabet in order to avoid planning confusion with "D-Day" being planned for Iwo Jima) would occur on 1 April 1945. Hardly a man failed to comment on the obvious irony: it was April Fool's Day and Easter Sunday — which would prevail?

The U.S. Fifth Fleet constituted an awesome sight as it sortied from Ulithi Atoll and a dozen other ports and anchorages to steam towards the Ryukyus. Those Marines who had returned to the Pacific from the original amphibious offensive at Guadalcanal some 31 months earlier marveled at the profusion of assault ships and landing craft. The new vessels covered the horizon, a mind-boggling sight.

On 26 March, the 77th Infantry Division kicked off the campaign by its skillful seizure of the Kerama Retto, a move which surprised the Japanese and produced great operational dividends. Admiral Turner now had a series of sheltered anchorages to repair ships likely to be damaged by Japanese air attacks — and already kamikazes were exacting a toll. The soldiers also discovered the main cache of Japanese suicide boats, nearly 300 power boats equipped with high-explosive rams intended to sink the thin-skinned troop transports in their anchorages off the west coast of Okinawa. The Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, Force Reconnaissance Battalion, commanded by Major James L. Jones, USMC, preceded each Army landing with stealthy scouting missions the preceding night. Jones' Marines also scouted the barren sand spits of Keise Shima and found them undefended. With that welcome news, the Army landed a battery of 155mm "Long Toms" on the small islets and soon added their considerable firepower to the naval bombardment of the south west coast of Okinawa. Meanwhile, Turner's minesweepers had their hands full clearing approach lanes to the Hagushi Beaches. Navy Underwater Demolition Teams, augmented by Marines, blew up hundreds of man-made obstacles in the shallows. And in a full week of preliminary bombardment, the fire support ships delivered more than 25,000 rounds of five-inch shells or larger. The shelling produced more spectacle than destruction, however, because the invaders still believed General Ushijima's forces would be arrayed around the beaches and air fields. A bombardment of that scale and duration would have saved many lives at Iwo Jima; at Okinawa this precious ordnance produced few tangible results. A Japanese soldier observing the huge armada bearing down on Okinawa wrote in his diary, "it's like a frog meeting a snake and waiting for the snake to eat him." Tensions ran high among the U.S. transports as well. The 60mm mortar section of Company K, 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, learned that casualty rates on L-Day could reach 80-85 percent. "This was not conducive to a good night's sleep," remarked Private First Class Eugene B. Sledge, a veteran of the Peleliu landing. On board another transport, combat correspondent Ernie Pyle sat down to a last hot meal with the enlisted Marines: "Fattening us up for the kill; the boys say," he reported. On board a nearby LST, a platoon commander rehearsed his troops in the use of home-made scaling ladders to surmount a concrete wall just beyond the beaches. "Remember, don't stop — get off that wall, or somebody's gonna get hurt."

|