| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

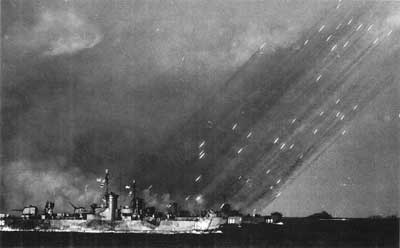

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) L-Day and Movement to Contact Operation Iceberg got off to a roaring start. The few Japanese still in the vicinity of the main assault at first light on L-Day, 1 April 1945, could immediately sense the wisdom of General Ushijima in conceding the landing to the Americans. The enormous armada, assembled from ports all over the Pacific Ocean, had concentrated on schedule off Okinawa's southwest coast and stood coiled to project its 182,000-man landing force over the beach. This would be the ultimate forcible entry, the epitome of all the amphibious lessons learned so painstakingly from the crude beginnings at Guadalcanal and North Africa. Admiral Turner made his final review of weather conditions in the amphibious objective area. As at Iwo Jima, the amphibians would be blessed with good weather on the critical first day of the landing. Skies would be cloudy to clear, winds moderate east to northeast, surf moderate, temperature 75 degrees. At 0406 Turner announced "Land the Landing Force," the familiar phrase which marked the sequential countdown to the first assault waves hitting the beaches at H-Hour. Combat troops already manning the rails of their transports then witnessed an unforgettable display of naval power — the sustained bombardment by shells and rockets from hundreds of ships, alternating with formations of attack aircraft streaking low over the beaches, bombing and strafing at will. Enemy return fire seemed scattered and ineffectual, even against such a mass of lucrative targets assembled offshore. Turner confirmed H-Hour at 0830.

Now came the turn of the 2d Marine Division and the ships of the Diversionary Force to decoy the Japanese with a feint landing on the opposite coast. The ersatz amphibious force steamed into position, launched amphibian tractors and Higgins boats, loaded them conspicuously with combat-equipped Marines, then dispatched them towards Minatoga Beach in seven waves. Paying careful attention to the clock, the fourth wave commander crossed the line of departure exactly at 0830, the time of the real H-Hour on the west coast. The LVTs and boats then turned sharply away and returned to the transports, mission accomplished. There is little doubt that the diversionary landing (and a repeat performance the following day) achieved its purpose. In fact, General Ushijima retained major, front-line infantry and artillery units in the Minatoga area for several weeks thereafter as a contingency against a secondary landing he fully anticipated. The garrison also reported to IGHQ on L-Day morning that "enemy landing attempt on east coast completely foiled with heavy losses to enemy."

But the successful deception came at considerable cost. Japanese kamikazes, convinced that this was the main landing, struck the small force that same morning, seriously damaging the troopship Hinsdale and LST 844. The 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, and the 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion suffered nearly 50 casualties; the two ships lost an equal number of sailors. Ironically, the division expected to have the least damage or casualties in the L-Day battle lost more men than any other division in the Tenth Army that day. Complained division Operations Officer Lieutenant Colonel Samuel G. Taxis: "We had asked for air cover for the feint but were told the threat would be 'incidental.'" On the southwest approaches, the main body experienced no such interference. An extensive coral reef provided an offshore barrier to the Hagushi beaches, but by 1945 reefs no longer posed a problem to the landing force. Unlike Tarawa, where the reef dominated the tactical development of the battle, General Buckner at Okinawa had more than 1,400 LVTs to transport his assault echelons from ship to shore without hesitation. These long lines of LVTs now extended nearly eight miles as they churned across the line of departure on the heels of 360 armored LVT-As, whose turret-mounted, snub-nosed 75mm howitzers blasted away at the beach as they advanced the final 4,000 yards. Behind the LVTs came nearly 700 DUKWs, amphibious trucks, bearing the first of the direct support artillery battalions. The horizon behind the DUKWs seemed filled with lines of landing boats. These would pause at the reef to marry with outward bound LVTs. Soldiers and Marines alike had rehearsed transfer line operations exhaustively. There would be no break in the assault's momentum this day.

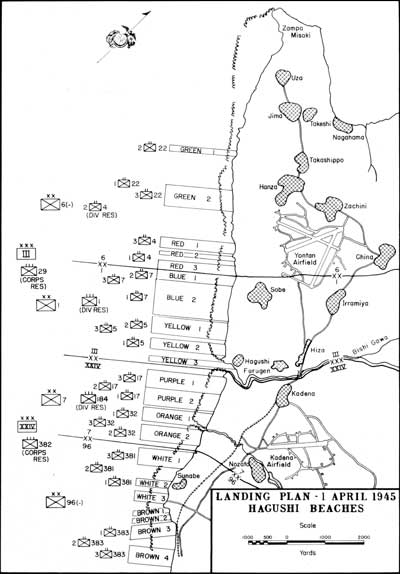

The mouth of the Bishi Gawa (River) marked the boundary between the XXIV Corps and IIIAC along the Hagushi beaches. The Marines' tactical plan called for the two divisions to land abreast, the 1st on the right, the 6th on the left. Each division in turn landed with two regiments abreast. The assault regiments, from north to south, were the 22d, 4th, 7th, and 5th Marines. Reflecting years of practice, the first assault wave touched down close to 0830, the designated H-Hour. The Marines stormed out of their LVTs, swarmed over the berms and seawalls, and entered the great unknown. The forcible invasion of Okinawa had begun. Within the first hour the Tenth Army had put 16,000 combat troops ashore. The assault troops experienced a universal shock during the ship-to-shore movement. In spite of the dire intelligence predictions and their own combat experience, the troops found the landing to be a cakewalk — virtually unopposed. Private First Class Gene Sledge's mortar section went in singing "Little Brown Jug" at the top of its lungs. Corporal James L. Day, a rifle squad leader attached to Company F, 2d Battalion, 22d Marines, who had landed at Eniwetok and Guam earlier, couldn't believe his good luck: "I didn't hear a single shot all morning — it was unbelievable!" Most veterans expected an eruption of enemy fire any moment. Later in the day General del Valle's LVT became stuck in a pothole enroute to the beach, the vehicle becoming a very lucrative, immobile target. "It was the worst 20 minutes I ever spent in my life," he said.

The morning continued to offer pleasant surprises to the invaders. They found no mines along the beaches, discovered the main bridge over the Bishi River still intact and — wonder of wonders — both airfields relatively undefended. The 6th Marine Division seized Yontan Airfield by 1300; the 7th Infantry Division had no problems securing nearby Kadena. The rapid clearance of the immediate beaches by the assault units left plenty of room for follow-on forces, and the division commanders did not hesitate to accelerate the landing of tanks, artillery battalions, and reserves. The mammoth build-up proceeded with only a few glitches. Four artillery pieces went down when their DUKWs foundered along the reef. Several Sherman tanks grounded on the reef. And the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, reached the transfer line by 1800 but had to spend an uncomfortable night in its boats when sufficient LVTs could not be mustered at that hour for the final leg. These were minor inconveniences. Incredibly, by day's end, the Tenth Army had 60,000 troops ashore, occupying an expanded beachhead eight miles long and two miles deep. This was the real measure of effectiveness of the Fifth Fleet's proven amphibious proficiency.

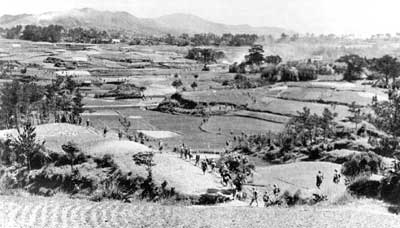

The huge landing was not entirely bloodless. Snipers wounded Major John H. Gustafson, commanding the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, late in the afternoon. Other men went down to enemy mortar and machine gun fire. But the losses of the entire Tenth Army, including the hard-luck 2d Marine Division, amounted to 28 killed, 104 wounded, and 27 missing on L-Day. This represented barely 10 percent of the casualties sustained by the V Amphibious Corps the first day on Iwo Jima. Nor did the momentum of the assault slow appreciably after the Tenth Army broke out of the beachhead. The 7th Infantry Division reached the East Coast on the second day. On the third day, the 1st Marine Division seized the Katchin Peninsula, effectively cutting the island in two. By that date, IIIAC elements had reached objectives thought originally to require 11 days in the taking. Lieutenant Colonel Victor H. Krulak, operations officer for the 6th Marine Division, recalls General Shepherd telling him, "Go ahead! Plow ahead as fast as you can. We've got these fellows on the run." "Well, hell," said Krulak, "we didn't have them on the run. They weren't there."

As the 6th Marine Division swung north and the 1st Marine Division moved out to the west and northwest, their immediate problems stemmed not from the Japanese but from a sluggish supply system, still being processed over the beach. The reef-side transfer line worked well for troops but poorly for cargo. Navy beachmasters labored to construct an elaborate causeway to the reef, but in the meantime, the 1st Marine Division demonstrated some of its amphibious logistics know-how learned "on-the-job" at Peleliu. It mounted swinging cranes on powered causeways and secured the craft to the seaward side of the reef. Boats would pull alongside in deep water; the crane would lift nets filled with combat cargo from the boats into the open hatches of a DUKW or LVT waiting on the shoreward side for the final run to the beach. This worked so well that the division had to divide its assets among the other divisions within the Tenth Army. Beach congestion also slowed the process. Both Marine divisions resorted to using their replacement drafts as shore party teams. Their in experience in this vital work, combined with the constant call for groups as replacements, caused problems of traffic control, establishment of functional supply dumps, and pilferage. This was nothing new; other divisions in earlier operations had encountered the same circumstances. The rapidly advancing assault divisions had a critical need for motor transport and bulk fuel, but these proved slow to land and distribute. Okinawa's rudimentary road network further compounded the problem. Colonel Edward W. Snedeker, commanding the 7th Marines, summarized the situation after the landing in this candid report: "The movement from the west coast landing beaches of Okinawa across the island was most difficult because of the rugged terrain crossed. It was physically exhausting for personnel who had been on transports a long time. It also presented initially an impossible supply problem in the Seventh's zone of action because of the lack of roads."

|