| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

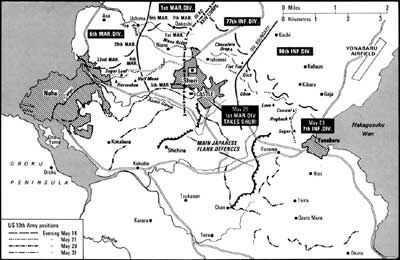

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) Assault on Shuri The 7th Marines was an experienced outfit and well commanded by Guadalcanal and Bougainville veteran Colonel Edward W. Snedeker. "I was especially fortunate at Okinawa," he said, "in that each of my battalion commanders had fought at Peleliu." Nevertheless, the regiment had its hands full with Dakeshi Ridge. "It was our most difficult mission," said Snedeker. After a day of intense fighting, Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley's 1/7 fought its way to the crest of Dakeshi, but had to withdraw under swarming Japanese counterattacks. The next day, Lieutenant Colonel Spencer S. Berger's 2/7 regained the crest and cut down the counterattackers emerging from their reverse-slope bunkers. The 7th Marines were on Dakeshi to stay, another significant breakthrough. "The Old Breed" Marines enjoyed only a brief elation at this achievement because from Dakeshi they could glimpse the difficulties yet to come. In fact, the next 1,200 yards of their advance would eat up 18 days of fighting. In this case, seizing Wana Ridge would be tough, but the most formidable obstacle would be steep, twisted Wana Draw that rambled just to the south, a deadly killing ground, surrounded by towering cliffs pocked with caves, with every possible approach strewn with mines and covered by interlocking fire. "Wana Draw proved to be the toughest assignment the 1st Division was to encounter," reported General Oliver P. Smith. The remnants of the 62d Infantry Division would defend Wana to their deaths. Because the 6th Marine Division's celebrated assault on Sugar Loaf Hill occurred during the same period, historians have not paid as much attention to the 1st Division's parallel efforts against the Wana defenses. But Wana turned out to be almost as deadly a "mankiller" as Sugar Loaf and its bloody environs. The 1st Marines, now led by Colonel Arthur T. Mason, began the assault on the Wana complex on 12 May. In time, all three infantry regiments would take their turn attacking the narrow gorge to the south. The division continued to make full use of its tank battalion. The Sherman medium tanks and attached Army flame tanks were indispensable in both their assault and direct fire support roles (see sidebar). On 16 May, as an indicator, the 1st Tank Battalion fired nearly 5,000 rounds of 75mm and 173,000 rounds of .30-caliber ammunition, plus 600 gallons of napalm. Crossing the floor of the gorge continued to be a heart-stopping race against a gauntlet of enemy fire, however, and progress came extremely slowly. Typical of the fighting was the division's summary for its aggregate progress on 18 May: "Gains were measured by yards won, lost, then won again." On 20 May, Lieutenant Colonel Stephen V. Sabol's 3/1 improvised a different method of dislodging Japanese defenders from their reverse-slope positions in Wana Draw. In five hours of muddy, back breaking work, troops manhandled several drums of napalm up the north side of the ridge. There the Marines split the barrels open, tumbled them down into the gorge, and set them ablaze by dropping white phosphorous grenades in their wake. But each small success seemed to be undermined by the Japanese ability to reinforce and resupply their positions during darkness, usually screened by mortar barrages or small-unit counterattacks. The fighting in such close quarters was vicious and deadly. General del Valle watched in alarm as his casualties mounted daily. The 7th Marines, which lost 700 men taking Dakeshi, lost 500 more in its first five days fighting for the Wana complex. During 16-19 May, Lieutenant Colonel E. Hunter Hurst's 3/7 lost 12 officers among the rifle companies. The other regiments suffered proportionately. Throughout the period 11-30 May, the division would lose 200 Marines for every 100 yards advanced. Heavy rains resumed on 22 May and continued for the next ten days. The 1st Marine Division's sector contained no roads. With his LVTs committed to delivering ammunition and extracting casualties, del Valle resorted to using his replacement drafts to hand-carry food and water to the front lines. This proved less than satisfactory. "You can't move it all on foot," noted del Valle. Marine torpedo bombers flying out of Yontan began air-dropping supplies by parachute, even though low ceilings, heavy rains, and enemy fire made for hazardous duty. The division commander did everything in his power to keep his troops supplied, supported, reinforced, and motivated — but conditions were extremely grim. To the west, the neighboring 6th Marine Division's advance south below the Asa River collided against a trio of low hills dominating the open country leading up to Shuri Ridge. The first of these hills — steep but unassuming — became known as Sugar Loaf. To the southeast lay Half Moon Hill, to the southwest Horseshoe Hill and the village of Takamotoji. The three hills represented a singular defensive complex; in fact they were the western anchor of the Shuri Line. So sophisticated were the mutually supporting defenses of the three hills that an attack on one would prove futile unless the others were simultaneously invested. Colonel Seiko Mita and his 15th Independent Mixed Regiment defended this sector. Its mortars and antitank guns were particularly well sited on Horseshoe. The western slopes of Half Moon contained some of the most effective machine gun nests the Marines had yet encountered. Sugar Loaf itself contained elaborate concrete-reinforced reverse-slope positions. And all approaches to the complex fell within the beaten zone of heavy artillery from Shuri Ridge which dominated the battlefield.

Battlefield contour maps indicate Sugar Loaf had a modest elevation of 230 feet; Half Moon, 220; Horseshoe, 190. In relative terms, Sugar Loaf, though steep, only rose about 50 feet above the northern approaches. This was no Mount Suribachi; its significance lay in the ingenuity of its defensive fortifications and the ferocity with which General Ushijima would counterattack each U.S. penetration. In this regard, the Sugar Loaf complex more closely resembled a smaller version of Iwo Jima's Turkey Knob/Amphitheater sector. As a tactical objective, Sugar Loaf itself lacked the physical dimensions to accommodate anything larger than a rifle company. But eight days of fighting for the small ridge would chew up a series of very good companies from two regiments. Of all the contestants, American or Japanese, who survived the struggle for Sugar Loaf, Corporal James L. Day, a squad leader from Weapons Company, 2/22, had indisputably the "best seat in the house" to observe the battle. In a little-known aspect of this epic story, Day spent four days and three nights isolated in a shell hole on Sugar Loaf's western shoulder. This proved to be an awesome but unenviable experience. Corporal Day received orders on 12 May to recross the Asa River and support the assault of Company G, 2/22, against the small ridge. Day and his squad arrived too late to do much more than cover the fighting withdrawal of the remnants from the summit. The company lost half its number in the day-long assault, including its plucky commander, Captain Owen T. Stebbins, shot in both legs by a Japanese Nambu machine-gunner. Day described Stebbins as "a brave man whose tactical plan for assaulting Sugar Loaf became the pattern for successive units to follow." Concerned about the unrestricted fire from the Half Moon Hill region, Major Henry A. Courtney, Jr., battalion executive officer, took Corporal Day with him on the 13th on a hazardous trek to the 29th Marines to coordinate the forthcoming attacks. With the 29th then committed to protecting 2/22's left flank, Courtney assigned Day and his squad in support of Company F for the next day's assault. Day's rifle squad consisted of seven Marines by that time. On the 14th, they joined Fox Company's assault, reached the hill, scampered up the left shoulder ("you could get to the top in 15 seconds"). Day then received orders to take his squad back around the hill to take up a defensive position on the right (western) shoulder. This took some doing. By late afternoon, Fox Company had been driven off its exposed position on the left shoulder, leaving Day with just two surviving squad-mates occupying a large shell hole on the opposite shoulder.

During the evening, unknown to Day, Major Courtney gathered 45 volunteers from George and Fox companies and led them back up the left shoulder of Sugar Loaf. In hours of desperate, close-in fighting, the Japanese killed Major Courtney and half his improvised force. "We didn't know who they were," recalled Day, "because even though they were only 50 yards away, they were on the opposite side of the crest. Out of visual contact. But we knew they were Marines and we knew they were in trouble. We did our part by shooting and grenading every [Japanese] we saw moving in their direction." Day and his two men then heard the sounds of the remnants of Courtney's force being evacuated down the hill and knew they were again alone on Sugar Loaf. Representing in effect an advance combat outpost on the contested ridge did not particularly bother the 19-year-old corporal. Day's biggest concerns were letting other Marines know they were up there and replenishing their ammo and grenades. "Before dawn I went back down the hill. A couple of LVTs had been trying to deliver critical supplies to the folks who'd made the earlier penetration. Both had been knocked out just north of the hill. I was able to raid those disabled vehicles several times for grenades, ammo, and rations. We were fine." On 15 May, Day and his men watched another Marine assault develop from the northeast. Again there were Marines on the eastern crest of the hill, but fully exposed to raking fire from Half Moon and mortars from Horseshoe. Day's Marines directed well-aimed rifle fire into a column of Japanese running towards Sugar Loaf from Horseshoe, "but we really needed a machine gun." Good fortune provided a .30-caliber, air-cooled M1919A4 in the wake of the retreating Marines. But as soon as Day's gunner placed the weapon in action on the forward parapet of the hole, a Japanese 47mm crew opened up from Horseshoe, killing the Marine and destroying the gun. Now there were just two riflemen on the ridgetop. Tragedy also struck the 1st Battalion, 22d Marines, on the 15th. A withering Japanese bombardment caught the command group assembled at their observation post planning the next assault. Shellfire killed the commander, Major Thomas J. Myers, and wounded every company commander, as well as the CO and XO of the supporting tank company. Of the death of Major Myers, General Shepherd exclaimed, "It's the greatest single loss the Division has sustained. Myers was an outstanding leader." Major Earl J. Cook, battalion executive officer, took command and continued attack preparations. The division staff released this doleful warning that midnight: "Because of the commanding ground which he occupies the enemy is able to accurately locate our OPs and CPs. The dangerous practice of permitting unnecessary crowding and exposure in such areas has already had serious consequences." The warning was meaningless. Commanders had to observe the action in order to command. Exposure to interdictive fire was the cost of doing business as an infantry battalion commander. The next afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Jean W. Moreau, commanding 1/29, received a serious wound when a Japanese shell hit his observation post squarely. Major Robert P. Neuffer, Moreau's exec, assumed command. Several hours later a Japanese shell wounded Major Malcolm "O" Donohoo, commanding 3/22. Major George B. Kantner, his exec, took over. The battle continued. The night of 15-16 seemed endless to Corporal Day and his surviving squadmate, Private First Class Dale Bertoli. "The Japs knew we were the only ones up there and gave us their full attention. We had plenty of grenades and ammo, but it got pretty hairy." The south slope of Sugar Loaf is the steepest. The Japanese would emerge from their reverse slope caves, but they faced a difficult ascent to get to the Marines on the military crest. Hearing them scramble up the rocks alerted Day and Bertoli to greet them with grenades. Those of the enemy who survived this mini-barrage would find themselves backlit by flares as they struggled over the crest. Day and Bertoli, back to back against the dark side of the crater, shot them readily.

"The 16th was the day I thought Sugar Loaf would fall," said Day. He and Bertoli hunkered down as Marine tanks, artillery, and mortars pounded the ridge and its supporting bastions. "We looked back and see the whole battle shaping up, a great panorama." This was the turn of 1/3/22, well supported by tanks. But Day could also see that the Japanese fires had not slackened at all. "The real danger at Sugar Loaf was not the hill itself, where we were, but in a 300-yard by 300-yard killing zone which the Marines had to cross to approach the hill from our lines to the north . . . . It was a dismal sight, men falling, tanks getting knocked out . . . . the division probably suffered 600 casualties that day. In retrospect, the 6th Marine Division considered 16 May to be "the bitterest day of the entire campaign." By then the 22d Marines was down to 40 percent effectiveness and General Shepherd relieved it with the 29th Marines. He also decided to install fresh leadership in the regiment, replacing the commander and executive officer with the team of Colonel Harold C. Roberts and Lieutenant Colonel August C. Larson. The weather cleared enough during the late afternoon of the 16th to enable Day and Bertoli to see well past Horseshoe Hill, "all the way to the Asato River." The view was not encouraging. Steady columns of Japanese reinforcements streamed northward, through Takamotoji village, towards the contested battlefield. "We kept firing on them from 500 yards away," still maintaining the small but persistent thorn in the flesh of the Japanese defenses. Their rifle fire attracted considerable attention from prowling squads of Japanese raiders that night. "They came at us from 2130 on," recalled Day, "and all we could do was keep tossing grenades and firing our M-1s." Concerned Marines north of Sugar Loaf, hearing the nocturnal ruckus, tried to assist with mortar fire. "This helped, but it came a little too close." Both Day and Bertoli were wounded by Japanese shrapnel and burned by "friendly" white phosphorous.

Early on the 17th a runner from the 29th Marines scrambled up to the shell-pocked crater with orders for the two Marines to "get the hell out." A massive bombardment by air, naval gunfire, and artillery would soon saturate the ridge in preparation of a fresh assault. Day and Bertoli readily complied. Exhausted, reeking, and partially deafened, they stumbled back to safety and an intense series of debriefings by staff officers. Meanwhile, a thundering bombardment crashed down on the three hills. The 17th of May marked the fifth day of the battle for Sugar Loaf. Now it was the turn of Easy Company, 2/29, to assault the complex of defenses. No unit displayed greater valor, yet Easy Company's four separate assaults fared little better than their many predecessors. At midpoint of these desperate assaults, the 29th Marines reported to division, "E Co. moved to top of ridge and had 30 men south of Sugar Loaf; sustained two close-in charges; killed a hell of a lot of Nips; moved back to base to reform and are going again; will take it." But Sugar Loaf would not fall this day. At dusk, after prevailing in one more melee of bayonets, flashing knives, and bare hands against a particularly vicious counterattack, the company had to withdraw. It had lost 160 men.

The 18th of May marked the beginning of seemingly endless rains. Into the start of this soupy mess attacked Dog Company, 2/29, this time supported by more tanks which braved the minefields on both shoulders of Sugar Loaf to penetrate the no-man's land just to the south. When the Japanese poured out of their reverse-slope holes for yet another counterattack, the waiting tanks surprised and riddled them. Dog Company earned the distinction of becoming the first rifle company to hold Sugar Loaf overnight. The Marines would not relinquish that costly ground. But now the 29th Marines were pretty much shot up, and still Half Moon, Horseshoe, and Shuri remained to be assaulted. General Geiger adjusted the tactical boundaries slightly westward to allow the 1st Marine Division a shot at the eastern spur of Horseshoe, and he also released the 4th Marines from Corps reserve. General Shepherd deployed the fresh regiment into the battle on the 19th. The battle still raged. The 4th Marines sustained 70 casualties just in conducting the relief of lines with the 29th Marines. But with Sugar Loaf now in friendly hands, the momentum of the fight began to change. On 20 May, Lieutenant Colonel Reynolds H. Hayden's 1/4 and Lieutenant Colonel Bruno A. Hochmuth's 3/4 made impressive gains on either flank. By day's end, 2/4 held much of Half Moon, while 3/4 had seized a good portion of Horseshoe. As Corporal Day had warned, most Japanese reinforcements funneled into the fight from the southwest, so 3/4 prepared for nocturnal visitors at Horseshoe. These arrived in massive numbers, up to 700 Japanese soldiers and sailors, and surged against 3/4 much of the night. Hochmuth had a wealth of supporting arms: six artillery battalions in direct support at the onset of the attack, and up to 15 battalions at the height of the fighting. Throughout the crisis on Horseshoe, Hochmuth maintained a direct radio link with Lieutenant Colonel Bruce T. Hemphill, commanding 4/15, one of the support artillery firing battalions. This close exchange between commanders reduced the number of short rounds which might have otherwise decimated the defenders and allowed the 15th Marines to provide uncommonly accurate fire on the Japanese. The rain of shells blew great holes in the ranks of every Japanese advance; Marine riflemen met those who survived at bayonet point. The counterattackers died to the man.

Even with Hochmuth's victory the protracted battle of Sugar Loaf lacked a climactic finish. There would be no celebration ceremony here. Shuri Ridge loomed ahead, as did the sniper-infested ruins of Naha. Elements of the 1st Marine Division began bypassing the last of the Wana defenses to the east. The 6th Division slipped westward. Colonel Shapley's 4th Marines crossed the Asa River, now chest-high from the heavy rain fall, on 23 May. The III Amphibious Corps stood poised on the outskirts of Okinawa's capital city. The Army divisions in XXIV Corps matched the Marines' break throughs. On the east coast, the 96th Division seized Conical Hill, the Shuri Line's opposite anchor from Sugar Loaf, after weeks of bitter fighting. The 7th Division, in relief, seized Yonabaru on 22 May. Suddenly, the Thirty-second Army faced the threat of being cut off from both flanks. This time General Ushijima listened to Colonel Yahara's advice. Instead of fighting to the death at Shuri Castle, the army would take advantage of the awful weather and retreat southward to their final line of prepared defenses in the Kiyamu Peninsula. Ushijima executed this withdrawal masterfully. While American aviators spotted and interdicted the south-bound columns, they also reported other columns moving north. General Buckner assumed the enemy was simply rotating units still defending the Shuri defenses. But these northbound troops were ragtag units as signed to conduct a do-or-die rear guard. At this, they were eminently successful.

This was the situation encountered by the 1st Marine Division in its unexpectedly easy advance to Shuri Ridge on 29 May as described in the opening paragraphs. The 5th Marines suddenly possessed the abandoned castle. While General del Valle tried to placate the indignation of the 77th Division commander at the Marines' "intrusion" into his zone, he got another angry call from the Tenth Army. It seems that that the Company A, 1/5 company commander, a South Carolinian, had raised the Stars and Bars of the Confederacy over Shuri Castle instead of the Stars and Stripes. "Every damned outpost and O.P. that could see this started telephoning me," said del Valle, adding, "I had one hell of a hullabaloo converging on my telephone." Del Valle agreed to erect a proper flag, but it took him two days to get one through the intermittent fire of Ushijima's surviving rear guards. Lieutenant Colonel Richard P. Ross, commanding the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, raised this flag in the rain on the last day of May, then took cover. Unlike Sugar Loaf, Shuri Castle could be seen from all over southern Okinawa, and every Japanese gunner within range opened up on the hated colors. The Stars and Stripes fluttered over Shuri Castle, and the fearsome Yonabaru-Shuri-Naha defensive masterpiece had been decisively breached. But the Thirty-second Army remained as deadly a fighting force as ever. It was an army that would die hard defending the final eight miles of shell-pocked, rain-soaked southern Okinawa.

|