| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

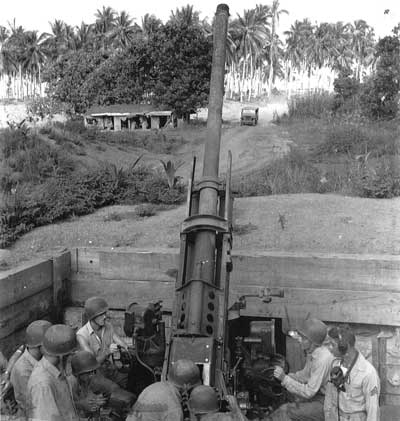

CONDITION RED: Marine Defense Battalions in World War II by Major Charles D. Melson South Pacific Tales Marines serving in the defense battalions learned lessons — some of them immortalized in legend — not taught in training or in the manuals. They learned about "air-raid coffee," strong enough to "lift one's scalp several inches per gulp." Coffee pots would go on the fire when things were quiet; then the air-raid alarm would signal Condition Red, which meant that an air raid was imminent, and the Marines would man their battle stations, sometimes for hours, waiting for and fighting off the attackers as the coffee boiled merrily away. The resulting brew became thick enough to eat with a fork, and Master Technical Sergeant Theodore C. Link claimed that the coffee "snapped back at the drinker." Veterans also learned to take advantage of members of newly arrived units, lavishly supplied but inexperienced in the ways of the world. A widely told story related how "wolf-hungry" Marines, who had been subsisting on canned rations, smelled steaks cooking at a field galley run by another service. As Technical Sergeant Asa Bordages told it, a Marine shouted "Condition Red! Condition Red!" The air raid signal sent the newcomers scrambling for cover, and by the time they realized it was a false alarm, the Marines were gone, and so were the steaks.

While American forces secured Guadalcanal and improved the security of the supply line to Australia and New Zealand, increasing numbers of Marines arrived in the Pacific, many of them members of defense battalions. The number of these units totaled 14 at the end of 1942, and the Marine Corps continued to form new ones into the following year. Three other divisions were activated during 1943, and a sixth would take shape during 1944. As the Pacific campaigns progressed, the various divisions and other units were assigned in varying combinations to corps commands. Eventually the V Amphibious Corps operated from Hawaii westward; the I Marine Amphibious Corps had its headquarters on Noumea but would become the III Amphibious Corps on 15 April 1944, before it moved its base to the liberated island of Guam. From Guadalcanal, the Marines joined in advancing into the central and northern Solomons during the summer and fall of 1943, forming one jaw of a pincers designed to converge on the Japanese base at Rabaul on the island of New Britain. While General Douglas MacArthur, the Army officer in command in the Southwest Pacific, masterminded the Rabaul campaign as an initial step toward the liberation of the Philippines, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz prepared for a thrust across the Pacific from Hawaii through the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. By the end of 1943, Marines would gain a lodgment in the northern Solomons and land in the Gilberts and on New Britain; clearly the United States was on the move.

Once the American counteroffensive got under way in earnest, the mission of the typical defense battalion changed. Initially, the defense battalions were expected to land at a site already under friendly control — either a previously developed base or a beachhead secured by assault troops — and remain until relieved. In actual practice, this concept did not work, for it overlooked the vulnerability of amphibious forces, especially to aerial attack, during and immediately after a landing. Experience dictated that the defense battalions land with the assault waves, whenever possible, and immediately set up their weapons. Besides protecting the beachhead during its most vulnerable period, the battalions freed other elements of the Fleet Marine Force from responsibility for guarding airfields and harbors. Whatever their role, the defense battalions received less coverage in the press than airmen, infantry, or raiders. A veteran of the 11th Defense Battalion, Donald T. Regan, who would become Secretary of the Treasury in the cabinet of President Ronald Reagan, remembered the anonymity that cloaked these units. "I felt," he said, "we were doing quite a bit to protect those who were doing the more public fighting." In providing this protection, in which Regan took such pride, defense battalions on Guadalcanal operated long-range radar integrated with the control network of Marine Aircraft Group 23. Lieutenant Colonel Walter L. J. Bayler — the last man off Wake Island, who had carried dispatches to Pearl Harbor on the only Navy plane to reach Wake during the siege — declared that the group's fighters were "highly successful in the destruction of enemy aircraft" whenever the improvised warning system was functioning. This experience may well have influenced a decision to convene a radar board at Marine Corps headquarters.

Formed in February 1943, the board was headed by Bayler and included Lieutenant Colonel Edward C. Dyer, who was thoroughly familiar with the techniques and equipment used by Britain's Royal Air Force to direct fighters. The board standardized procedures for "plotting, filtering, telling, and warning," as the radar specialists fed information to a direction center that integrated antiaircraft and coastal defense, the primary responsibilities of the defense battalions, with the interception of attacking aircraft by pilots of the Marine Corps, Army, or Navy. The radar board refused, moreover, to lift the veil of secrecy that concealed the radar program, directing that "no further items on the subject would be released" until the Army and Navy were convinced the enemy already had the information from some other source.

|