| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

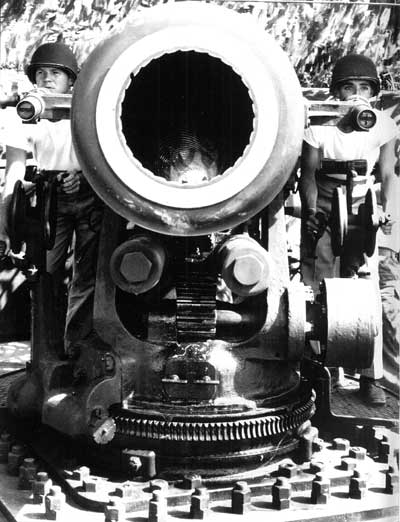

CONDITION RED: Marine Defense Battalions in World War II by Major Charles D. Melson Japan, its military leaders confident they — could stagger the United States and gain time to seize the oil and and other natural resources necessary to dominate the western Pacific, attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, sinking or badly damaging 18 ships, destroying some 200 aircraft, and killing more than 2,300 American servicemen. Though caught by surprise, Marines of the 1st, 3d, and 4th Defense Battalions standing guard in Hawaii fought back as best they could. Few heavy weapons were yet in place, and ammunition remained stored on ship board, along with many of the guns. Nevertheless, these units had eight antiaircraft machine guns in action within six minutes after the first bombs exploded at 0755. By 0820, 13 machine guns were manned and ready, and they cut loose when a second wave of Japanese aircraft began its attack a few minutes later. Unfortunately, shells for the 3-inch antiaircraft guns did not reach the hurriedly deployed firing batteries until after the second and final wave of attacking aircraft had completed its deadly work. The Marines responded to the surprise raid with small arms and an eventual total of 25 machine guns, claiming the destruction of three aircraft during the morning's fighting.

As the Japanese aircraft carriers withdrew after the raid on Pearl Harbor, a pair of enemy destroyers began shelling Midway Island shortly before midnight on 7 December to neutralize the aircraft based there. A salvo directed against Midway's Sand Island struck the power plant, which served as the command post of the 6th Defense Battalion, grievously wounding First Lieutenant George H. Cannon. He remained at his post until the other Marines wounded by the same shell could be cared for and his communications specialist, Corporal Harold Hazelwood, had put the battalion switchboard back into action. Cannon, who died of his wounds, earned the first Medal of Honor awarded a Marine officer during World War II. Hazelwood received a Navy Cross. Base Defense in a Possible War with Japan For decades before Japan gambled its future on a war with the United States, the Marine Corps developed the doctrine, equipment, and organization needed for just such a conflict. Although the Army provided troops for the defense of the Philippines, the westernmost American possession in the Pacific, the Marine Corps faced two formidable challenges: placing garrisons on any of the smaller possessions that the Navy might use as bases at the onset of war; and seizing and defending the additional naval bases that would enable the United States to project its power to the very shores of Japan's Home Is lands. A succession of Orange war plans — Orange stood for Japan in a series of color-coded planning documents — provided the strategy for the amphibious offensive required to defeat Japan and the defensive measures to protect the bases upon which the American campaign would depend. As a militaristic Japan made in roads into China in the 1930s, concern heightened for the security of Wake, Midway, Johnston, and Palmyra Islands, the outposts protecting Hawaii, a vital staging area for a war in the Pacific. (Although actually atolls — tiny islands clustered on a reef-fringed lagoon — Wake, Midway, Johnston, and Palmyra have traditionally been referred to as islands.) By 1937, the Marine Corps was discussing the establishment of battalion-size security detachments on the key Pacific outposts, and the following year's War Plan Orange proposed dispatching this sort of defense detachment to three of the Hawaiian outposts — Wake, Midway, and Johnston. The 1938 plan called for a detachment of 28 officers and 428 enlisted Marines at Midway, armed with 5-inch coastal defense guns, 3-inch antiaircraft weapons, searchlights for illuminating targets at night, and machine guns. The Wake detachment, similarly equipped, was to be slightly smaller, 25 officers and 420 enlisted men. The Johnston Island group would consist of just nine officers and 126 enlisted men and have only the antiaircraft guns, searchlights, and machine guns. The plan called for the units to deploy by M-Day — the date of an American mobilization for war — "in sufficient strength to repel minor naval raids and raids by small landing parties." In the fall of 1938, an inspection party visited the sites to look for possible gun positions and fields of fire and to validate the initial man power estimates.

Meanwhile, a Congressionally authorized board, headed by Admiral Arthur J. Hepburn, a former Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, investigated the need to acquire additional naval bases in preparation for war. While determining that Guam, surrounded by Japanese possessions, could not be defended; the Hepburn Board emphasized the importance of Midway, Wake, Johnston, and Palmyra. As a result, during 1939 and 1940, Colonel Harry K. Pickett — Marine Officer, 14th Naval District, and Commanding Officer, Marine Barracks, Pearl Harbor Navy Yard — made detailed surveys of the four atolls. In 1940, the Army and Navy blended the various color plans, including Orange, into a series of Rainbow Plans designed to meet a threat from Germany, Japan, and Italy acting in concert. The plan that seemed most realistic, Rainbow 5, envisioned that an Anglo-American coalition would wage war against all three potential enemies, defeating Germany first, while conducting only limit ed offensive operations in the Pacific, and ultimately throwing the full weight of the alliance against Japan. Such was the basic strategy in effect when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

|