| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

CONDITION RED: Marine Defense Battalions in World War II by Major Charles D. Melson An Organization for Base Defense The interest of the Marine Corps in base defense predated the proposal in the Orange Plan of 1937 to install defense detachments at Wake, Midway, and Johnston Islands. Although the spirit of the offensive predominated over the years, both the Advanced Base Force, 1914-1919, and the Fleet Marine Force, established in 1933, trained to defend the territory they seized. In 1936, despite the absence of primarily defensive units, the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico, Virginia, taught a 10-month course in base defense, stressing coordination among aviation, antiaircraft, and artillery.

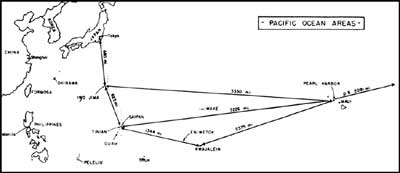

The increasingly volatile situation in the Pacific, which led ultimately to war, the evolving Orange plan for a war against Japan, and the long time interest of the Marine Corps in base defense set the stage for the creation of defense battalions to garrison the crescent of outposts stretching from Wake and Midway to Samoa. Influenced by American isolationist attitudes, Major General Commandant Thomas Holcomb decided to ask for funds to form new defensive — rather than offensive — units. In carrying out the provisions of the plan for a conflict with Orange, the Commandant intended to make the best use of appropriated funds, which had only begun to increase after the outbreak of war in Europe during September 1939. In doing so he reminded the public that the Marine Corps would play a vital role in defending the nation. After the war, General Gerald C. Thomas recalled in his oral history that General Holcomb realized that Congress was unlikely to vote money for purely offensive purposes as long as the United States remained at peace. At a time when even battleships and heavy bombers were being touted as defensive weapons, Holcomb seized on the concept of defense battalions as a means of increasing the strength of the Corps beyond the current 19,432 officers and men. Two officers at Marine Corps headquarters, Colonel Charles D. Barrett and Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Pepper, turned concept into reality by drawing up detailed plans for organizations expressly designed to defend advance bases. The Kentucky-born Barrett entered the Marine Corps in 1909, served in the occupation of Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914, and during World War II would become a major general; in 1943, while commanding I Marine Amphibious Corps, he died as a result of an accident. Pepper, would rise to the rank of lieutenant general, assuming command of Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, after the war. Aware that isolationism still gripped the United States in 1939, the two planners emphasized the defensive mission of the new units, stressing their ability to "hold areas for the ultimate offensive operations of the Fleet." As the danger of war with Japan increased, the first of several 900-man defense battalions took shape in the United States. Each of the new outfits consisted of three antiaircraft batteries, three seacoast batteries, ground and antiaircraft machine gun batteries, and a team of specialists in administration and weapons maintenance. In late 1939, when the Marine Corps formed its first defense battalions, the future was still obscure. Japan remained heavily engaged in China, but a "phony war" persisted in western Europe. At Marine Corps headquarters, some advocates of the defense battalions may have felt that these new units were all the service would need by way of expansion, at least for now. On the other hand, within the G-3 Division of Holcomb's staff, officers like Colonel Pedro A. del Valle kept their eyes fixed on a more ambitious goal, the organization of Marine divisions. Eventually, the Marine Corps would expand, creating six divisions and reaching a maximum strength in excess of 450,000, but the frenzied growth occurred after Japan attacked the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

In the immediate aftermath of the outbreak of war in Europe and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's declaration of a limited national emergency, the Marine Corps grew by small increments that included the defense battalions. To explain the role of these units, General Holcomb in 1940 circulated throughout the Corps a classified document drafted by First Lieutenant Robert D. Heinl, Jr., who would serve in a wartime defense battalion, become the author of widely read articles and books and active in the Marine Corps historical program, and attain the grade of colonel. Heinl declared that "through sheer necessity, the Marine Corps has devised a sort of expeditionary coast artillery capable of occupying an untenanted and undefended locality, of installing an all around sea-air defense, and this within three days." In his annual report to the Secretary of the Navy for the fiscal year ending in June 1940, General Holcomb stated that four battalions had been established and two others authorized. "The use of all six of these defense battalions can be foreseen in existing plans," he wrote, adding that the fleet commanders had already requested additional units of this type. The new organizations took advantage of the latest advances in automatic weapons, radios, tanks, coast and antiaircraft artillery, sound-ranging gear, and the new mystery — radar. Teams of specialists, which had mastered an array of technical skills, it was hoped would enable a comparatively small unit to defend a beachhead or airfield complex against attack from the sea or sky. As time passed and strategic circumstances changed, the defense battalions varied in strength, weaponry, and other gear. As an official historical summary of the defense battalions has pointed out, their composition also reflected "the geographic nature of their location and the availability of equipment." Consequently, the same battalion might require a different mix of specialists over the years.

|