| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

CONDITION RED: Marine Defense Battalions in World War II by Major Charles D. Melson Fighting Boredom One technique used by a defense battalion's communications specialists in the battle against boredom consisted of eavesdropping on the radio nets used by the fighter pilots. The chatter among aviators, though discouraged by commanders, rivaled the dialogue in the adventure serials broadcast in late afternoon back in the United States — radio shows such as Captain Midnight or Hop Harrigan. First Lieutenant William K. Holt remembered hearing cries of: "I'm Deadeye Dick, I never miss"; or, borrowing directly from a yet another radio serial, "Here comes Jack Armstrong, the all-American boy." Imitations of machine gun fire punctuated the commentary. By the end of 1943, as the program reached its peak wartime strength, 19 defense battalions had been organized. One of the early units, the 5th Defense Battalion, was redesignated as the 14th Defense Battalion, so that the 19 units accounted for 20 numbers. At the peak of the program, 26,685 Marines and sailors served in the 19 defense battalions, a figure that does not include the various replacement drafts that kept them at or near authorized strength. Since a Marine division in 1943 required some 19,000 officers and enlisted men, the pool of experienced persons assigned to the defense battalions made these units a target for reorganization and consolidation as the war approached a climax.

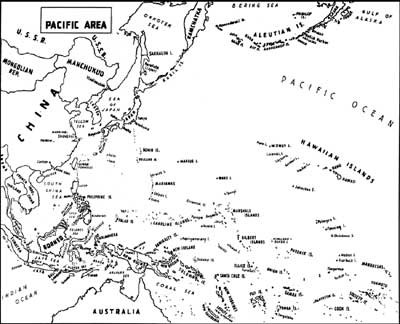

Defense battalions supported the attack by V Amphibious Corps across the Central Pacific, an offensive that began in November 1943 with the storming of two main objectives, Makin and Tarawa, in the Gilbert Islands. Long-range bombers based in the Ellice Islands helped prepare the atolls for the impending assault, and the 5th and 7th Defense Battalions protected the bases these aircraft used from retaliatory air strikes by the Japanese.

In the bloodiest fighting of the Gilberts operation, the 2d Marine Division stormed Betio Island in Tarawa Atoll on 20 November and overwhelmed the objective within four days. On 24 November, the last day of the fighting, Colonel Norman E. True's 2d Defense Battalion relieved the assault units that had captured Betio. The defense battalion set up guns and searchlights to protect the airstrip on Betio — repaired and named Hawkins Field after First Lieutenant William D. Hawkins, one of the 2d Marine Division's heroes killed in the battle — and another airfield built by Seabees at adjacent Bonkiri. The defenders emplaced radar and searchlights to guard against night bombing raids, employing a combination of radar-directed and free-lance searchlights that could pick up approaching aircraft at a slant range of 60,000 feet. Between November 1943 and January 1944, the Japanese hurled 19 air raids against True's battalion, along with numerous harassing raids by lone airplanes known as "Washing-Machine Charlie." Only once did the enemy escape detection. According to one of the unit's officers, Captain John V. Alden, the Japanese raiders usually aimed for the airfields, often mistaking the beach for the runways at night and, in one instance, hitting gun positions on the coast of Bairiki. On 28 November 1943, the 8th Defense Battalion, commanded by Colonel Lloyd L. Leech, went ashore at Apamama, an atoll in the Gilberts captured with a minimum of casualties, to relieve the Marine assault force that had landed there. Apamama lay just 80 miles from blood-drenched Tarawa, but for First Lieutenant James G. Lucas, a Marine Corps combat correspondent, it was "difficult to imagine they were in the same world." Japanese bombers from the Marshall Islands sometimes raid ed Apamama, recalled Sergeant David N. Austin of the antiaircraft group, and one moonlit night the gunners "fired 54 rounds before the cease-fire came over the phone." The bold thrust through the Gilberts penetrated the outermost ring of Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific. The next objectives lay in the Marshall Islands, where in a fast-paced series of assaults V Amphibious Corps used Marine reconnaissance troops and Army infantry to attack Majuro on 30 January 1944 and, immediately afterward, two objectives in Kwajalein Atoll. The 4th Marine Division assaulted Roi Namur — actually two islets joined by a causeway — on the 31st, and an Army infantry division landed at Kwajalein Island on 1 February. A mixed force of Marines and soldiers stormed Eniwetok Atoll, at the western limit of the Marshall group, on 17 February. Those who watched from shipboard off Roi-Namur saw "pillars of greasy smoke billow upward." This awesome sight convinced an eyewitness, Master Technical Sergeant David Dempsey, a combat correspondent, that the preliminary bombardment by aircraft and naval guns must have blasted the objective to oblivion, but somehow the Japanese emerged from the shattered bunkers and fought back.

The 1st Defense Battalion, under Colonel Lewis A. Hohn, and the 15th, led by Lieutenant Colonel Francis B. Loomis, arrived in the Mar shalls and initially emplaced their weapons at Roi-Namur and Majuro. On Roi, the defenders set up antiaircraft guns in some of the 50 or more craters gouged in the Japanese runways by American bombs and shells. Machine gunner Ed Gough recalled that his special weapons group came ashore "on the first or second day," remaining "through the first air raid when the Japanese succeeded in kicking our ass." The enemy could not, however, overcome the antiaircraft defenses, and calm settled over the captured Marshalls. Marines from the defense battalions helped is landers displaced by the war to return to Roi-Namur, where, upon coming home, they helped bury the enemy dead and clear the wreckage from a "three-quarter-square-mile junk yard." Tractors, trucks, and jeeps ground ceaselessly across the airfield on Roi bringing in construction material for new installations and removing the rubble. Colonel Hohn's battalion moved on to Kwajalein Island and Eniwetok Atoll by the end of January, and Lieutenant Colonel Wallace O. Thompson's 10th Defense Battalion joined them on 21 February. The victory in the Marshalls advanced the Pacific battle lines 2,500 miles closer to Japan. Far to the south, the African American 51st Defense Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Curtis W. LeGette, landed at the Ellice Islands in February 1944. One glance at the isolated chain of desolate islands suggested that the white Marines of the departing 7th Defense Battalion "were never so glad to see black people" in their lives. The 51st took over airfield defense and engaged in gun drills and practice alerts, finally firing on a radar return from a suspected surfaced Japanese submarine on 28 March. The 51st assumed responsibility for defending Eniwetok in September, replacing the 10th Defense Battalion, but actual combat continued to elude the black Marines despite unceasing preparation.

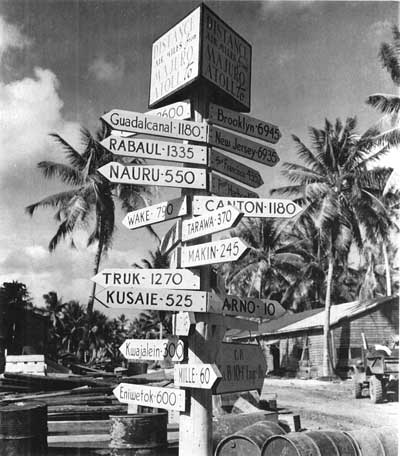

Once established ashore in the Gilberts and Marshalls, the defense battalions rarely, if ever, faced the threat of marauding Japanese ships or aircraft. As the active battlefields moved closer to Japan, the phenomenon of sign-painting took hold. One of them summarized the increasing isolation of the defense battalions from the fury of the island war. "Shady Acres Rifle and Gun Club," read the sign, "Where Life Is a 155mm Bore." Such was the forgotten war on the little islands, described as "almost microscopic in the incredible vastness of the Pacific," which became stops on the supply lines that sustained other Marines fighting hundreds of miles away. According to one observer, the captured atolls served as "stopovers for the long, gray convoys heading westward," though some of them also became fixed aircraft carriers for bombing the by-passed enemy bases. While the defense battalions prepared for attacks that did not come, a relatively small number of airmen harassed thousands of Japanese left behind in the Marshall and Caroline Islands.

|