| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

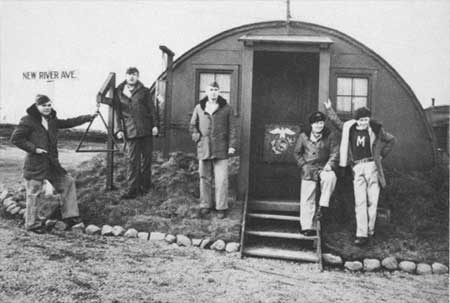

OUTPOST IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC: Marines in the Defense of Iceland by Colonel James A. Donovan, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret)

Some joint Army-Marine command post exercises were conducted for the staffs. When the weather and darkness began to restrict field training, some units of the brigade initiated schooling for both officers and enlisted Marines. The 1st Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Oliver P. Smith, who was well schooled himself and a graduate of France's Ecole de Guerre Superieure, held officers' schools on military subjects. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel William A. Worton, commander of the 2d Battalion, was interested in establishing literacy classes in "everything from simple arithmetic to calculus." Lieutenant William C. Chamberlin, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Dartmouth College, who had been working in his spare time on his doctorate degree at the University of Iceland, was made "Headmaster" of the battalion's schools which employed officer and NCO teachers. Eventually more than 125 Marines attended classes in a variety of basic subjects. It helped to keep young minds busy when they had very little else to occupy their spare time. Before it had become too dark during the days, there had been a fair amount of range firing of crew-served weapons—machine guns and mortars—but field exercises were just no longer feasible now. During their deployment to Iceland, the firing batteries of the 2d Battalion, 10th Marines, had been attached in support of the three infantry battalions of the 6th Marines and initially were located adjacent to the infantry camps. In the late fall, the batteries were returned to their parent battalion control and relocated at a new camp, Camp Tientsin. This move was made to facilitate artillery technical training and permit more efficient field firing planning and execution by the battalion.

In the ever-darker winter weeks, almost all military training came to a standstill. Close-order drill in the morning by moonlight was just not effective. Rifles' barrels had to be inspected indoors by lamp light reflected from a thumbnail placed in the chamber. Some weapons drills were held in the huts. Much time was dedicated to ensuring the health and comfort of the Marines without losing sight of the defense mission. It wasn't easy. The wind blew constantly with gusts of 70 to 100 miles per hour and the Marines settled down to whatever training they could conduct in their quarters. A traditional pastime which always kept Marines busy was to maintain personal gear with "spit and polish." The M1903 Springfield rifle had a wooden stock made of carefully selected walnut. It took a beautiful polish when linseed oil was rubbed into the wood by the Marine's palm. His rifle was his personal weapon, constantly inspected and handled with care and pride. The other habitual Marine practice was to shine the issue chocolate brown-colored, high-top leather shoes to a high gloss. Dealing with their own and their Marines' sheer boredom became a real problem for both junior and senior commanders. Mail call, though the letters and packages often arrived late in battered and tattered condition, very often wet, was a highlight in a day's schedule. Enlisted marines were issued two free cans of beer per day from the post exchange, an event which also broke the monotony. As always, card games for high stakes were a popular pastime. Most of the gamblers' pay "rode the books" as there was no place to spend it. Because there was little to read, one company commander often to a book to his men's huts and read to them as they and their salty and grizzled NCOs sat at his feet and listened with rapt attention. Some nights he sneaked in a bottle of whiskey for the men. They described these visits as "the skipper's mail call."

With the advancing cold weather and snow, each battalion formed an ad hoc "ski patrol" with a potential mission of rescuing crews of downed aircraft or to find persons lost in the rugged country. The patrol consisted of an officer and a few men, mostly from New England, who claimed to be experienced skiers. Their chief problem was that they had no supply of proper ski boots or bindings or wax. The skis purchased in Charleston were simple wooden ones with a toe strap only, and the poles provided were basic beginner's bamboo sticks. The snow was never deep enough around Marine camps for good skiing and fortunately there were no emergencies calling for a ski patrol rescue. As noted earlier, a major difficulty facing Marine units in remote outpost camps was the shortage of transportation. Marine infantry battalions had no motor transport of their own—neither jeeps nor trucks, prime movers nor weapons carriers. The 2d Battalion, 10th Marines, had small, one-ton truck prime movers for its 75mm pack howitzers. The brigade had a motor transport platoon with some old two-ton trucks. The defense battalion had a few vehicles, but there were no general-purpose, staff, command, or utility vehicles in the brigade. Only the generosity of the U.S. and British armies, which loaned the Marines a small number of trucks enabled them to meet the most basic logistic requirements. The British had also loaned the Marines a few of their small "staff" or reconnaissance vehicles which were little more than four-cylinder sport cars painted olive drab. The Army generously provided the brigade with some jeeps and 3/4-ton trucks available to transport Marine working parties and for logistic support. Lack of motor transport was a continuing problem for the brigade for most of its time in Iceland. With the dearth of motor vehicles and material handling equipment, the Marines continued to move by foot and to use their backs to handle supplies. One benefit was that most enlisted ranks kept physically fit despite the lack of a formal physical fitness program.

Recreation for Marines in the city and vicinity of Reykjavik was very limited. The few existing restaurants were small, barely able to serve both the local citizens and a few British and American troops. There were only two small movie theaters and the Hotel Borg—the largest and best in town—which were the centers of the Icelanders' social life. The Borg attracted the Allied officers to its dances but was "out of bounds" to enlisted troops. Single girls frequented the hotel to dance with the officers and even to establish some promising friendships.

|