| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

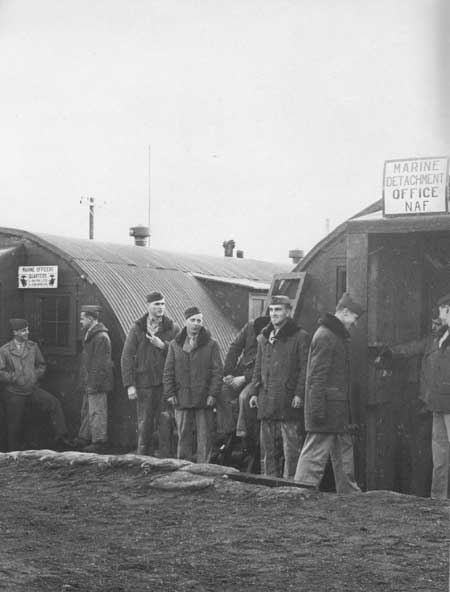

OUTPOST IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC: Marines in the Defense of Iceland by Colonel James A. Donovan, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) In the early spring of 1941, with the war in Europe a year and a half old, the recently formed 2d Marine Division trained for what observant Marines expected would be an amphibious war against the Japanese in the Pacific. The division was then stationed at Marine Corps Base, San Diego, and also at the newly opened Camp Elliott. Field training for the 6th Marines and the other 2d Division regiments (2d and 8th Marines, infantry; 10th Marines, artillery) was conducted in the scrubby hills and arroyos of Camp Elliott where large wooden, yellow-painted, Navy designed barracks housed the Marine companies and battalions at what is now Naval Air Station, Miramar. Some units were in nearby tent camps.

Unit training consisted of weapons schools, drills, and firing of individual and crew-served weapons. Small unit tactical exercises were run by companies, and there was a considerable number of long-distance hikes. The Marines had virtually no vehicles or motorized mobility, so nearly all movement was by foot. There were very few battalion or larger-unit filed exercises. Night training was minimal. In April, the 6th Marines' landing teams began a series of amphibious training exercises embarked in a group of recently modified freight/passenger ships procured for the purpose. Ship-to-shore drills were held on San Clemente Island, west of San Diego, using the recently developed Landing Craft Personnel (LCP) or "Higgins Boat." This boat had no ramp in the bow, so the Marines had to roll over the gunwales to debark. (The LCPR with a ramp at the bow was not widely available to Marines until after the landing on Guadalcanal in August 1942.) The 6th Marines received a warning order in May 1941 for a possible move to the East Coast to join the 1st Marine Division for contingency operations related to the war in Europe. At the time, the regiment was not yet up to peacetime strength, so the call went out to both the 2d and 8th Marines for volunteers—both officers and enlisted Marines—to augment the 6th. There was no shortage of volunteers. Colonel Leo D. "Dutch" Hermle, a much-decorated veteran of World War I, commanded the 6th Marines. For its move, the regiment was to be reinforced by the 2d Battalion, 10th Marines (with 12 75mm pack howitzers); Company A, 2d Tank Battalion, minus one platoon (with 12 light tanks); a parachute platoon; an antitank platoon; and the 1st Platoon, Company A, 2d Service Battalion. The regiment and the reinforcing units were brought up to a strength of 204 officers and 3,891 enlisted, Marines and Navy, following the arrival of 58 officers and 577 enlisted men from the other units of the division. The division ordered the reinforced regiment to take 10 units of fire for all weapons, gasoline, 30-days' rations, and other supplies. On 31 May, the reinforced 6th Marines mounted out of San Diego with orders to report to the Commanding General I Corps (Provisional), Fleet Marine Force, Atlantic Fleet. At that time, combat loading for an assault landing had not yet become as refined as it was to be later in the war. In any case, the regiment and its supporting units did not know where they were going or what their mission was to be, so the ships were loaded more for convenience than for combat. higher headquarters kept adding items to be embarked, leading some companies to take everything in their camp supply sheds. Most of the Marines embarking with the 6th believed that the force would go to the Caribbean region, so some officers packed summer service uniforms, dress whites, and summer and winter civilian dinner clothes, in addition to all their winter service uniforms. One credible rumor was that they were going to Martinique to guard an impounded Free French aircraft carrier against a potential German takeover. Still another rumor held the Azores as the objective. In the early spring of 1941, the British had, in fact, expressed concern about the security of the Azores which, if taken by the Germans, would threaten both Portugal and the British supply lines into the Mediterranean Sea. British and American staff planners meeting in Washington had been making contingency plans for the growing likelihood of America's participation in the war. In such a case, the United States would relieve the British of responsibility for the defense of Iceland, among other things. While the U.S. Army was rapidly expanding, it appeared that Congressional support for the draft was wavering, which meant the Army could not deploy units containing draftees overseas.

By late spring 1941, Britain's back was against the wall. Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to send American troops to Iceland to replace the British garrison there. The President agreed, provided the Icelanders invited an American occupation force to their island. Churchill, meanwhile, was having difficulty in securing the invitation and the reluctance of the Icelandic government to issue one very nearly upset an Anglo-American timetable already in process.

A large volcanic island on the edge of the Arctic Circle, Iceland was strategically located for the air and naval control of the North Atlantic "lifeline" between the British Isles and North America. In 1941, France having fallen, Britain alone faced Nazi Germany. Churchill knew that the survival of his nation depended upon support from the United States, and by no means could Iceland be allowed to fall into enemy hands.

At the end of May, the Joint Board of the Army and Navy, formed after the Spanish-American War to prepare joint war plans, approved a contingency plan to land some 28,000 U.S. Army troops and Marines on the Azores under Marine Major General Holland M. Smith. The 1st Marine Division would provide most of the Marine component, but at that time the division was expanding and its regiments were still understrength. It was then decided to reinforce the division with a regiment from the 2d Division and the task fell to the 6th Marines (Reinforced). Lieutenant General Leo D. Hermle

Lieutenant General Leo D. Hermle, who died in January 1976, was born in Hastings, Nebraska, in 1890, and was graduated from the University of California in 1917 with bachelor of arts and doctor of jurisprudence degrees. He reported for active duty as a Marine second lieutenant in August 1917, and sailed for France in February 1918 with the Sixth Marine Regiment. He participated with the regiment in all of its major battles in France, and for his service he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal, the Silver Star with an Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a second Silver Star, and the French Croix de Guerre with Palm and Diploma. He also was awarded the French Legion of Honor with the rank of Chevalier, and was cited twice in the General Orders of the 2d Division, American Expeditionary Forces. For five years after his return to the United States, he served as a legal officer at Marine Barracks, Mare Island, and in the office of the Judge Advocate General of the Navy. During the interwar period, he had duty in the States as well as overseas. As commander of the 6th Marines, he took his regiment to Charleston, South Carolina, where it became the nucleus of the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional), in June 1941, when it sailed for Iceland. Upon his return to Camp Elliott, California, in March 1942, Colonel Hermle became chief of staff of the 2d Marine Division and traveled with it when it was assigned to duty in the Pacific. Upon promotion to brigadier general, General Hermle became assistant division commander (ADC) of the 2d, and as such, participated with it in the assault of Tarawa. He returned to the West Coast to become ADC of the 5th Marine Division and landed with it in the invasion of Iwo Jima in February 1945. For his exploits, he received the Navy Cross. He was both deputy island commander and island commander of Guam, 1945-1946, and assumed command of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, in 1946, where he remained until his retirement in 1949, after more than 32 years of active service. For having been specially commended for his performance of duty in combat, he was advanced to the rank of lieutenant general on the retired list. he was a professor of law at the University of San Diego for many years following retirement. The ships carrying the 6th Marines consisted of three transports (APs). The 1st Battalion was in the USS Fuller (AP-14), the 2d Battalion in the USS Heywood (AP-12), and the 3d Battalion in the USS William P. Biddle (AP-15) with the regimental headquarters. Each transport's embarkation team included elements of the reinforcing units. There were two destroyer escorts and four fast destroyer transports (old four-stackers), stacks of each of two having been removed to make room for transporting one rifle company. The captains and executive officers of the transports were experienced regular Navy officers, but most of the remaining officers and men were recently called-up Reservists. many of the Marines on these ships had far more time at sea than did most of the ships' companies.

|