| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

OUTPOST IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC: Marines in the Defense of Iceland by Colonel James A. Donovan, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) While the Marines cruised south to Panama, the war situation in Europe prompted President Roosevelt to reconsider his plan for seizing and occupying Martinique or the Azores and turn his attention to the more immediate threat to Iceland and the relief of British forces there. Washington planners decided to form a provisional Marine brigade at Charleston, South Carolina, with the west coast Marines as its nucleus, augmented by the 5th Defense Battalion from Parris Island, South Carolina. The battalion had been organized at Parris Island on 1 December 1940, with a cadre of officers and men from the 4th Defense Battalion. Colonel Lloyd L. Leech was the initial commanding officer. When ordered to Charleston in June 1941, the 5th Battalion was only partially trained and under-equipped, so emergency requisitions went to U.S. Army antiaircraft artillery commands nationwide to provide the Marine battalion some new weapons and equipment, which were hastily delivered at dockside. Battalion personnel were embarked in the Orizaba (AP-24); guns and cargo were loaded on the USS Arcturus (AK-18) and the USS Hamul (AK-30), two new cargo ships.

The Marines were deployed to Iceland because they were all volunteers, and unlike the draftee-encumbered Army, could be ordered overseas. moreover, the 6th Marines was already at sea prepared for expeditionary duty. On 5 June, Roosevelt directed the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Harold R. Stark, to have a Marine brigade ready to sail in 15 day's time. The brigade was formed on 16 June, the day following the arrival of the 6th Marines (Reinforced) in Charleston. The 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional) was formally organized under Brigadier General John Marston. His new command consisted of: Brigade Headquarters Platoon; Brigade Band; 6th Marines (Reinforced); 2d Battalion, 10th Marines; 5th Defense Battalion (less its 5-inch Artillery Group, which remianed in the States); Company A, 2d Tank Battalion (less 3d Platoon); Company A, 2d Medical Battalion; Company C, 1st Engineer Battalion; 1st Platoon, Company A, 2d Service Battalion; 3d Platoon, 1st Scout Company; and Chemical Platoon. The parachute platoon was detached and reassigned to the 1st Marine Division, which happened also to be in Charleston when the 6th Marines arrived. General Marston arrived in Charleston on 18 June with a small brigade headquarters staff. Admiral Stark's mission statement for the brigade was simple and direct: In cooperation with the British garrison, defend Iceland against hostile attack.

The new brigade, consisting of 4,095 Marines, departed Charleston on 22 June. The men were not unhappy to leave the hot, humid, and noisy Navy yard. Most of the brigade's Marines were kept busy loading ships with additional supplies and equipment procured in Charleston by supply officers, and such incongruous items as skis, ski poles, and winter "protective clothing" purchased by supply officers at a local Sears Roebuck store.

Added to the convoy at Charleston were two cargo ships and two destroyers. It was met outside Charleston harbor by an impressive force of warships and escorts. When the entire convoy began its move towards the North Atlantic, it consisted of 25 vessels, including two battleships, the USS New York (BB-34) and USS Arkansas (BB-33), and two cruisers, USS Nashville (CL-43) and the USS Brooklyn (CL-40). While the convoy was underway, a Marine wrote a letter home on 27 June:

The ships did not yet have surface radar, and so Marines were added to the continuous submarine watches from deck stations. Frequent appearance of U.S. Navy PBY aircraft flying antisubmarine warfare (ASW) patrols reassured the convoy and its Marine passengers. The Marine's letter continued:

The convoy moved into Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, on the night of 27 June, leaving the fog outside. Some officers and men were allowed to go ashore at the small village of Argentia to stretch their legs and see the local scenery. Despite the windy, cold, wet weather, the battalions were able to get ashore at least one day for exercise and limited hikes, which helped to reduce the ill effects of too many hours of confinement and bunk duty on board the transports. During foul weather the only spaces troops had were below decks in their compartments and on their bunks. Major General John Marston

Major General John Marston, who died in November 1957, was born on 3 August 1884 in Pennsylvania, and was commissioned a Marine second lieutenant in June 1908. After five months' training at the School of Application at Annapolis, he began a period of barracks and sea-going duty. This culminated in assignment to the 1st Advance Base Regiment, which landed at and occupied Veracruz, Mexico, in January 1914. In 1915, then-First Lieutenant Marston was assigned to he Haitian Constabulary and operations against the bandit Cacos in Northern Haiti. After three years in Haiti, he served at the Naval Academy and at Quantico, until another overseas assignment, this time to the American Legation in Managua, Nicaragua, where he remained from 1922 to 1924. Following a number of assignments in the Quantico-Washington area, including a brief tour again in Nicaragua as a member of the U.S. Electoral Mission, in 1935 Colonel Marston was transferred to me American Embassy, Peiping. There he commanded the Marine Detachment, 1937-1938, and was senior commander of Marine forces in North China, 1938-1939. Brigadier General Marston became commander of the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional) in June 1941 and took it to Iceland. Upon return to the United States in April 1942, he was promoted to major general and given command of the 2d Marine Division, moving with it to New Zealand. He returned to the States in August 1942 and was appointed commander of the Department of the Pacific, with headquarters in San Francisco. In April 1944, he was named Commanding General, Camp Lejeune, and served in that position until 1946, when he retired to Lexington, Virginia. The interlude at Newfoundland "to await further orders" continued until 1 July, when the government of Iceland finally, and reluctantly, invited the American occupation that Winston Churchill had requested and promised. On the night of 1 July, the transports upped anchors at 2200 and slowly moved back out to sea headed for Iceland. During the following day, the transports steamed in file behind the Arkansas and New York. Fog drifted over the convoy, fog horns blew every few minutes, and all hands anxiously examined the ships' formation when the fog cleared. One day at officers' school the maps of Iceland were broken out and the staffs began to brief the company officers on the island, its terrain, weather, people, and what the mission would be. On 5 July, a more serious note was added when troops were ordered to wear life jackets at all times, for the convoy was entering the European war zone. Then at 2000 one night the destroyer on the starboard flank picked up a lifeboat with 14 survivors (four Red Cross women and 10 Norwegian sailors) of a ship torpedoed 200 miles to he south on 24 June. Their ships, the Vigrid, a Norwegian merchant ship, had developed engine trouble, fell behind its convoy, and was picked off by a German submarine. The next day the convoy went through the flotsam and jetsam of the British battleship HMS Hood, which had been sunk by the German pocket battleship Bismarck on 24 May. Items of equipment from the Hood floating alongside their ships brought the war to the close attention of sober Marines lining the rails of their transports.

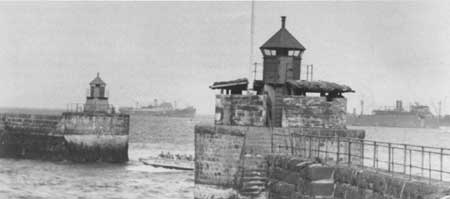

Early in the morning of 7 July, the brigade's convoy approached Iceland and the capital city of Reykjavik. The sea was glassy calm, the sun was well up and bright as it did not set in July in northern lands. The strong odor of fish floated out over the troop ships from the port. A couple of the transports were able to tie up at the small stone quays and Marines lined the rails to examine the people and sights of their new station. Earlier, in May 1941, a battalion of Royal Marines had landed and occupied the capital city, Reykjavik. Ten days later they were relieved by a Canadian Army brigade. The Canadians soon left for England and were replaced by British Army and Royal Air Force units. Some of the replacements were remnants of regiments which had been evacuated from Dunkirk. They were mostly Territorial Army units which are similar to the U.S. National Guard. Antiaircraft artillery units, air defense fighters, and patrol bombers also established island defense installations. Hvalfjordur, a deep fjord 35 miles north of Reykjavik, became the site of an important naval anchorage. Based at an airfield at Keflavik, about 30 miles south of Reykjavik, was a mixed bag of Royal Air Force aircraft including a few Hurricane fighters. It also held some patrol bombers: Hudsons, Sunderlands, and a small group of obsolescent float planes. Most of the British pilots at the field were veterans of the Battles of Britain and were sent to Keflavik for a spell of more relaxed duty. By the summer of 1941, the British contingent had about 25,000 troops in Iceland, including the Tyneside Scottish, the Durham Light Infantry, and the Duke of Wellington's Regiment in the 49th Division, as well as some Royal Artillery field batteries, Royal Army engineers, and other detachments. In addition, 500 RAF personnel and about 2,000 sailors, who manned and serviced the anti-submarine vessels and mine sweepers based at Hvalfjordur, were on the island. British soldiers ("Tommies") in their rugged battle-dress uniforms, heavy black boots, and garrison-type caps cocked over one ear, waved and yelled at the Marines as the American ships tied up at the quay. A few British officers also in battle dress but with peaked caps, swagger sticks, and gleaming leather walked along the quay examining the ships and their Marine passengers. British officers came on board to welcome the Marines and in due course departed with some of the senior brigade staff to confer about landing plans, camp areas, and missions. The cargo ships and the 5th defense Battalion had to unload at the quays, so the troop ships moved out in the harbor, from where they landed Marine style over a small rocky beach named "Balbo" using Higgins boats and a few tank lighters.

The Marines coming ashore from the transports appeared to be a motley crew wearing mixed uniforms and carrying odd personal baggage. Some wore service caps and some wore broad-brimmed campaign hats. Others were in working party blue coveralls, and still others in greens. Some Marines toted sea bags. Some had rifle-cleaning rods stuck in rifle barrels and strung with rolls of toilet paper, some carried their good blouses on coat hangers hooked to their rifles. The British soldiers didn't know what to make of the spectacle. But to be safe, they saluted all Marines who wore peaked caps and neckties because that is what their own officers wore.

One detail the British neglected to discuss with the Marines was the matter of tides in northern latitudes and neither the U.S. Navy nor the Marine planners seemed to be aware of the 14-foot tide which almost washed the landing force back from its small stony landing beach into the cold Arctic seas. Marines unloaded the ships by manhandling bulk cargo equipment, and ammunition from holds into cargo nets which were lowered into the landing craft alongside by the ships' large booms. The boats then ran the short distance to shore where Marine working parties again unloaded the cargo by hand and carried it up onto the beach. Because the Marines had few trucks, they were almost completely dependent upon Royal Army Service Corps two-ton lorries (trucks) to move supplies and equipment to destinations inland. It all went slowly and with hours the tide began to overtake the unloading. The sea came in and inundated the beaches and Marine supplies. Soon cardboard containers of rations, wool shirts, equipment, and supplies were awash or drifting out into the stream. It took a few days to salvage and dry out some of the gear. Regimental supplies and equipment coming into Balbo beach became mixed and piled up in great confusion. The value of the few tank lighters was apparent and the need for a ramp at the bow of the LCPs was also evident. Motorized material-handling equipment, palletized cargo, and weatherproof packing were in the future. Despite the problems with the tide and the narrow beach, the unloading proceeded around the clock. In four days the Marines manhandled and moved 1,500 tons of supplies and equipment from the three transports over the beach and into lorries and to the battalions' assigned camps, some as afar away as 15 miles.

|