| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

OUTPOST IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC: Marines in the Defense of Iceland by Colonel James A. Donovan, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) The question of command relations had surfaced early in the top-level discussions. The British desired that the brigade be placed under their direct command because they had the major force and its commander was senior to General Marston. But Admiral Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations, had reservations about attaching the marines to the army of a nation at war while the U.S. was still ostensibly neutral. Subsequently, General Marston's orders read that he would coordinate his operations "with the defense operations of the British by the method of mutual cooperation" while reporting directly to the CNO.

When British major General Henry O. Curtis suggested that the Marines wear the British forces' 49th Division Polar Bear shoulder patch, General Marston accepted for the Marines. "The mutual cooperation directive was working to the entire satisfaction of the British Commander and the Brigade. The British complied with our requests and we complied with theirs. It was as simple as that. Our reception by the British has been splendid," General Marston reported to the Major General Commandant on 11 July. "They [the British] have placed at our disposal all of their equipment and have rationed us for ten days to cover the period of disembarkation." The Marine brigade would war the 49th Division's polar-bear shoulder patch with considerable pride. The 49th Division's commander, General Curtis, became popular with the Marines of all ranks by a display of simple leadership and genuine interest in Marine activities, including trying his hand in their softball games.

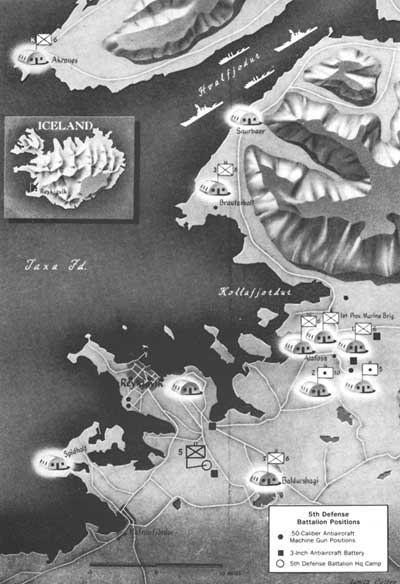

A special board of officers established by the brigade shortly after its arrival estimated the Germans had varied capabilities to threaten the security of Iceland. They could attempt an amphibious or airborne attack, they could bomb Allied forces and installations, or they could conduct some limited raids from the sea. However, the planning board judged that as long as the British Home Fleet maintained superiority in the seas north of Scotland and areas east of Iceland, the Germans would be unable to support any sizable or prolonged offensive against the Iceland base. The Marine brigade's mission was two-fold: the British division commander designated the 6th Marines (Reinforced), as a "mobile force" for use at any point along the winding coastal road leading from Reykjavik to the naval base at Hvalfjordur. The 5th Defense Battalion service as an air defense unit with the mission of protecting the city, the harbor, and the airfield from German attack. Brigade headquarters was established in the same camp where the 6th Marines headquarters was located — Camp Lumley near Reykjavik. Further up the road, the 1st Battalion occupied two adjacent camps, Victoria Park and Camp MacArthur, about 10 miles from Reykjavik. The camps were near the Varma River, which was unique because its waters were hot, with a temperature of about 90 degrees. It was fed from hot spring nearby and afforded the Marines a warm swimming hole. The 2d Battalion was located at Camp Baldurshagi, near the regimental headquarters. This was an attractive camp in a rocky valley with a stream feeding into a nearby river stocked with salmon. The Icelanders maintained strict fishing rights but the Marines were constantly tempted to cast a line.

In late September, the 3d Battalion was moved to Camp Brauterholt, which was on a wet, rugged, rocky peninsula located near the entrance of Hvalfjordur, the long, deep naval base fjord. The naval base anchorage was a key feature of the Iceland defense area. It was located some 45 miles up the jagged coast from Reykjavik and was surrounded by bleak mountains with no civilian houses nearby. The entrance to the fjord was closed by a submarine net and gate tended by a small British naval vessel. The route leading north to the fjord consisted of a desolate, one-way gravel road with frequent turnouts for passing. Boggy tundra ran along the roadside for some stretches. One side of the road was flanked by water and the other side by steep mountain slopes. The British, worried about parachute attacks, had prepared road blocks at selected locations along the road with fortified strong points. Small garrisons had orders to hold out against any attack until reserves could arrive. When the 3d Battalion assumed this mission, it posted a rifle platoon in a few huts of the key Saurbaer pass. A reinforced rifle company was also sent to the town of Akranes on the north side of the entrance to the fjord.

Camp Brauterholt was a small unfinished camp recently vacated by the British. At Brauterholt and the outposts there was no electricity and no plumbing, only open air heads and mud. The officers mess consisted of an Icelandic cow barn made partially livable by a British officer, a theater designer in civilian life, who painted the barn's walls with scenes of an English village pub. With a large mess table and an adequate galley, it became a center of officer life in the camp. Upon landing and offloading its equipment, the 5th Defense Battalion immediately coordinated with the British command and was integrated with the British defense forces around the port and airfield. The battalion command post was established at Camp Ontario and then moved to Camp Hilton in September. Within a week of landing, the battalion was training, establishing gun positions, and performing camp routines and maintenance. In addition to its three batteries of 3-inch antiaircraft artillery and a battery of 36 .50-caliber heavy water-cooled, antiaircraft machine guns, the 5th operated a number of searchlights and three SCR 268-type radar sets which were most secret and closely guarded. These were the first radars employed by U.S. Marines in the field. No one was allowed near the large rotating, bed-spring-like units, and they remained too secret to even discuss. With a strength of about 950 officers and enlisted Marines, the battalion was widely dispersed among a number of camps at their battery positions covering a considerable area. Battery personnel were located in some 10 small Nissen hut camps in the Reykjavik port and airfield defense sectors. The batteries supplied camp construction working parties which erected many of the Nissen huts and other camp and gun installations. Such construction projects continued until the battalion was redeployed back to the States.

|