| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

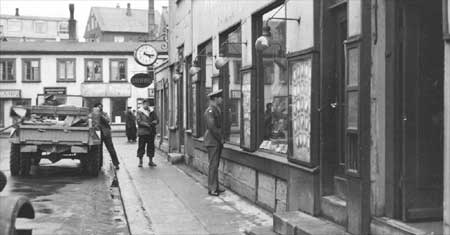

OUTPOST IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC: Marines in the Defense of Iceland by Colonel James A. Donovan, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) The staff non-commissioned officers had a favorite restaurant and the lower ranks made do with what facilities were left, which weren't much. Travel was so difficult that many Marines decided that going to town wasn't worth the effort required.

The Marines had brought with them a few musical instruments, such as guitars. As time passed, the Red Cross provided additional recreational equipment, radios, and record players. As the troops were forced to depend upon their own resources, they soon produced several clever and amusing shows.

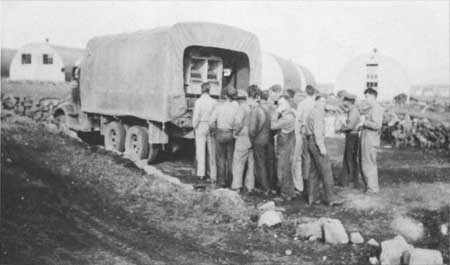

Movies for the Marines weren't available until September. The brigade had brought no projection equipment with its expeditionary combat gear. One projector was passed around the battalions of the brigade, which then used living huts or mess buildings for shows once or twice a week until they could finally build recreation huts. Eventually some of the camps were able to construct recreation huts for movie shows, where the small beer ration could be dispensed, and in which a small post exchange could be set up. Previously, a truck would visit the camps periodically with a selection of post exchange items such as smoking, washing, asn shaving supplies. During the winter months, the recreation buildings served to provide space for small libraries, barber service, amateur shows, classrooms, and religious services.

The battalion camp galleys were primitive at best and tested the skills of the cooks and frequently the stomachs of the Marines, but at least the rations were usually feshly prepared and warm. World War II combat rations had not yet appeared. Rations were never elaborate or fancy but were healthy and adequate. Meals were made with frozen, dried, and tinned foods prepared on old Marine Corps World War I-vintage, kerosene-burning, trailer-mounted "buzzacot" stoves. Beans, forzen fowl, salmon, mashed potatoes, corned beef, stew, canned fruits, posdered milk, coffee, and some baked goods were typical items on the menu. (Officers were charged fifty cents per day for rations.) The menu was repeated every ten days. There were no field combat rations. Troops ate from their Wolrd War I mess kits: two pans with a handle and steel spoon, knife, and fork. Each man washed his own mess kit in GI cans holding boiling soapy water followed by a dip in boiling clear water. Nobody suffered, but it was an intiquated system.

With the arrival of the Army, the Marines changed from Navy rations to the Army menu which included experimental field rations consisting largely of Spam, sausage, and dehydrated items. The Navy had been supplying an acceptable variety of canned and dried foods, but the new Army rations werent' very popular with most Marines. There was no refrigeration, no running water in the galleys, and no good way to heat water until the Army brough in No. 5 coal ranges and immersion heaters to heat water to boiling for washing the men's mess gear. Prior to this, water had been heated on the cooking ranges. The mess hals had rough wooden benches and tables, and both the galleys an mess halls were pungent with the odor of mutton and codfish obtained from local sources. Messmen described the day's menu as "mutton, lamb, sheep, or ram." Local milk and cheese products were prohibited because it was reported that many of Iceland's cows were tubercular. The Marines were issued a highly concentrated chocolate candy bar as a "combat" rations to be consumed in case the Germans attacked and other rations were not available. one gunnery sergeant dubbed this ration "the last-chance goody bar." Communications in the brigade were primitive even by the standards of World War II. The primary means of tactical and administrative communications were the land lines and sound-powered telephones whic h tied together companies, battalions, regiments, and brigade. Battalion and higher headquarters had radio equipment that could be broken down into man-pack loads and were powered by hand-cranked generators. Eventualy gasoline-powered generator units provided electricity for radios as well and camp lighting. World news and information of events at home came mostly from naval channels and personal mail, which took tow to four weeks to arrive via destroyers. A brigade weekly newspaper, The Artic Marine, provided some world ne3ws, American sports news, some local news items, and Marine humor.

|