|

The land administered as Mount Rainier National Park has been since time immemorial the Ancestral homeland of the Cowlitz, Muckleshoot, Nisqually, Puyallup, Squaxin Island, Yakama, and Coast Salish people. By following Elders’ instructions passed through generations, these Indigenous Peoples remain dedicated caretakers of this landscape. Their Traditional Knowledge and Management of this Sacred Land will endure in perpetuity, and we honor each nation’s traditions of landscape stewardship in our endeavors to care for, protect, and preserve the features and values of the mountain. From the Native American tribes who gathered resources in the area for millennia to the bustling park that exists on the land today, a wide variety of groups have found meaning and importance in the mountain now called Mount Rainier. All of these groups mapped their values on the landscape and contributed to a broader sense of what the area should be. Though these values were often very different and sometimes conflicted, they all played a part in shaping Mount Rainier National Park. The mountain is a product of its past in more than just a geological sense: understanding the human history of Mount Rainier is crucial to realizing the intricacy of the mountain today.

"Artwork by Michael Stasinos, originally published in “Berkeley Rockshelter Lithics: Understanding the Late Holocene Use of the Mount Rainier Area.” Bradford W. Andrews, Kipp O. Godfrey, and Greg C. Burtchard. Journal of Northwest Anthropology, 50(2):16 Early Human HistoryFor millennia, the ancestors of modern tribes came to the mountain seasonally to hunt and gather resources. In subalpine regions, early humans hunted mountain goats and gathered huckleberries and other plants. In the lower-elevation forests, they collected cedar bark to weave into baskets and hats and fished in the rivers flowing from the mountain. Far from being an “untouched” wilderness, the landscape of the mountain has long been utilized and shaped by humans. Many of these traditional activities continue to this day. Tribal members return to the park to camp and recreate. Each of the tribes associated with the mountain have their own names for this iconic peak: Tahoma, Takhoma, Tacoma, Ta-co-bet, Taqo ma, Tkobed, Taqo bid, Tkomen, Nutselip, Pshwawanoapami-tahoma, and others.

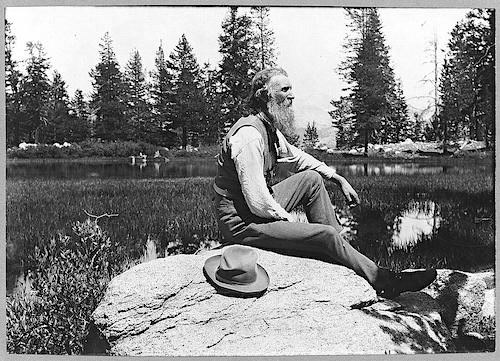

NPS Photo Changing Populations: 1792-1800sThe mountain captivated early European and American visitors. Captain George Vancouver of the British Royal Navy observed the mountain while surveying the Pacific coast in 1792 and decided to name the mountain after his friend, Rear Admiral Peter Rainier. Rear Admiral Rainier never saw the mountain named for him in person. In 1854-1855 three tribal treaties, the Treaty of Medicine Creek, the Treaty of Point Elliot, and the Treaty with the Yakama, ceded lands of the Nisqually, Puyallup, Steilacoom, Squaxin, Yakama, and other bands to the United States, including the area around Mount Rainier. The treaties include provisions that native people could continue to hunt and gather on the land, though interpretation of the treaties varied. Mountaineers made some of the first non-native incursions on land, eager to summit the iconic peak. P.B. Van Trump and General Hazard Stevens made the first recorded climb of the mountain in 1870, after being led to a basecamp near Paradise by a native guide known as Sluiskin. Other climbers and explorers would soon follow. In 1883, James Longmire, on his way down from summiting the mountain, found a mineral spring and opened a hotel and spa there not long after. The entrepreneurial spirit and scenic appreciation for the mountain that drove Longmire would emerge as key themes in the future development of Mount Rainier National Park.

Library of Congress Creation of the parkIt was not predetermined that Mount Rainier would become a national park. A growing interest in timber led to the formation of the Pacific Forest Reserve in 1893, a rough square, thirty-five miles on a side, with Mount Rainier’s summit on the western edge. Then in 1897, the area was renamed the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve and the boundaries were greatly enlarged to the west and south. Several mining claims were made in the area and some of the early explorers, like Bailey Willis, were geologists surveying the area for minerals. However, scientists, mountaineers, conservation groups, local businesses, and large railroad companies all saw some possible benefit from a national park around Mount Rainier. They combined their often-disparate interests into a lobbying campaign starting in 1893. It stressed the potential for tourism from the nearby cities of Seattle and Tacoma, the unsuitability of land for other commercial purposes like agriculture and grazing, and a need to preserve the unique glacial landscape for further study. After hesitant congressmen received assurances that the park would not come as an added expense to the government, the bill passed in 1899. Mount Rainier became the nation’s fifth national park.

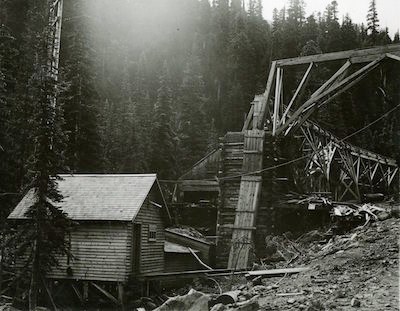

NPS Photo Early Years: 1899-1915The advent of automobiles increased the accessibility of the park but also created new challenges. The Nisqually Entrance Road, also called Government Road, was the first road constructed in the park beginning in 1904. The road was planned by a landscape architect to artfully move visitors through the mountainous landscape to Longmire and then to Paradise. Mount Rainier was the first national park to allow personal vehicles and to collect entrance fees in 1907. The road to Paradise Park was finished in 1911, making travel to the mountain even easier. Development at the park grew at a torrid and often chaotic pace. Visitation ballooned from 1,786 in 1906 to 34,814 nine years later and park administrators struggled to keep up with the constant demand for more roads, lodging, and other services. Concurrent with the growth in tourist activity was an increased commercial interest in the natural resources of the park. During the first fifteen years of the park’s existence and in the absence of established regulations, mining, water development, and timber schemes sprang up but met with limited success. Congress passed legislation in 1908 preventing further mining claims within the park, and remaining claims were slowly bought back over the following decades.

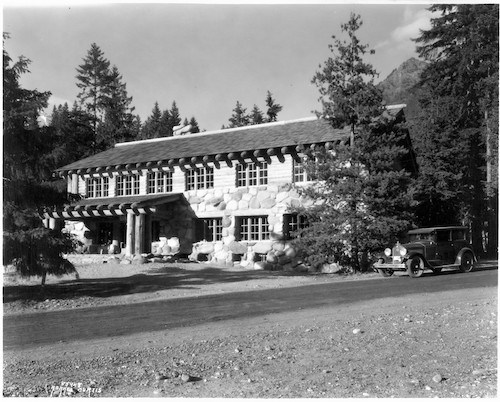

Asahel Curtis/Mount Rainier National Park Archives Development of the National Park Service: 1916-1930The creation of the National Park Service in 1916 brought significant changes to Mount Rainier. Park rangers began to take on a greater role in managing the park, including starting interpretive programs in 1921. This early period before the Great Depression was also key for the development of park infrastructure. At Longmire, a new style of architecture was being developed. Early buildings like the Longmire Library (1910) and Museum (1916), were simple, wooden structures. In designing the Longmire Administration Building in the 1920s, National Park Service architects in San Francisco decided to make a building that looks like it belonged here: a rustic building constructed with local stone and wood echoing the surrounding forests and mountains. Soon to be known as “National Park Service Rustic”, this style of architecture became a model for buildings across the National Park Service. At Mount Rainier, NPS Rustic architecture can be found in the design of numerous buildings in the park, as well as historic structures like Christine Falls Bridge. Some experimentation in design can be found in the park as well. The Paradise Inn, modeled after a European alpine resort, opened in 1917, while plans to develop Sunrise envisioned structures in the style of a frontier fort.

NPS Photo Great Depression and WWII: 1931-1945During the Great Depression, the park was forced to shift its goals and priorities. Visitation initially fell, leading to new efforts to attract sightseers. A nine-hole golf course at Paradise and plans for a ski lift provide just a few examples. The Sunrise Road was completed in 1931, but the frontier fort-style buildings, now home to the Sunrise Visitor Center, took several years to finish. The Sunrise Lodge was never fully completed and was left as a day lodge. Cabins around the lodge were sold off to the Defense Department during WWII as worker housing. President Roosevelt’s "New Deal" brought new funding to Mount Rainier. Between 1933-1940, over 1,000 men from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) came each summer to work on trail construction, campground improvement, and forest fire protection. A boundary expansion in 1931 pushed the park’s boundary east to the Cascade Range, bringing the Ohanapecosh area within the park boundaries. Funding and visitation plummeted during World War II, though the park did find new use as a training ground for the army’s new mountain divisions.

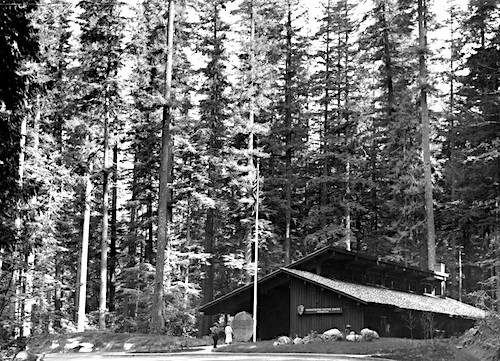

NPS Photo Mission 66 Era: 1945-1965After World War II, the focus of the park shifted toward managing the extreme increase in visitor use. During the mid-1950s, the federal government’s Mission 66 project sought to upgrade and expand visitor facilities at national parks while relieving the congestion that accompanied increased day use. Mount Rainier was the first national park to develop a Mission 66 plan as the park exemplified several nationwide trends – greater use of cars, shorter stays, and growing use overall. The program provided money for new park buildings, roads, and trails to ease congestion and spread use around the park. At Mount Rainier National Park, a good example of Mission 66 is the development of the Ohanapecosh Area as an alternative to the crowded Paradise and Sunrise areas. The Ohanapecosh Visitor Center was completed in 1964 and the campground was greatly expanded with additional loops. Improved employee housing and maintenance facilities were constructed. The east and west sides of the park were finally linked in 1957 when Stevens Canyon Road was completed, 25 years after it was started, connecting Ohanapecosh to Paradise with a new picnic area at Box Canyon. At Paradise, a new road route was constructed, and the old road turned into a one-way scenic loop, the Paradise Valley Road, to better guide the flow of increased traffic in the popular area. A new visitor center was also built at Paradise. Based on Mount Rainier as a prototype, Mission 66 aimed to absorb the impact of larger numbers of visitors without “impairment” to the parks by rearranging the patterns of visitor use.

NPS Photo Shifts in park management: 1966-1990sIncreased visitor use led to increased impact on the natural resources of the park and a realization that more was needed to preserve them for the enjoyment of all. Though visitation has shown considerable variability, it swelled to over 2.5 million people visiting the park in 1977. Attempts to summit Mount Rainier had grown almost tenfold since 1965. In response to these shifts, the park zoned the mountain into different use areas to manage the various impacts of recreation. After the Wilderness Act of 1964 and a boom in wilderness recreation during the late 1960s, a new backcountry management plan was created in 1973. Under the plan, restrictions on campfires, horse use, and camping site capacity aimed to minimize damage to wilderness areas. The Washington Wilderness Act of 1988 designated 97% of the park as wilderness, giving these lands greater protection against development. Coinciding with the broader environmental movement and the passage of the Clean Air Act (1970), Clean Water Act (1972), and Endangered Species Act (1973), the park management refocused on meadow restoration efforts, more intensive surveys of the park’s wildlife and plants, and studies of the mountain’s glaciers and rivers. Between 1915 and 1972, over nine million fish were stocked into lakes and streams within Mount Rainier National Park. The park historically prioritized recreational fishing, but a better understanding of natural ecosystems brought recognition that non-native fish compete with native fish and amphibians. Fish stocking was halted after 1972. However, approximately 35 mountain lakes within the park continue to support breeding populations of non-native fish to this day and fishing is encouraged to reduce non-native fish amounts.

NPS Photo An ever-changing park: 2000 – Present DayAs designated wilderness and a National Historic Landmark District, Mount Rainier National Park has a strong obligation to protect both the natural and cultural resources of the park. At the same time, visitation has continued to grow, with congestion at park entrances, parking lots, and visitor areas impacting visitor experiences. Efforts to modernize the park have included building a new visitor center at Paradise in 2008, replacing the exhibits in the Sunrise Visitor Center in 2010, and updating outdoor exhibit panels throughout the park. Historic structures like the Paradise Inn (2006-2008), Chinook Entrance Arch (2012), and the Paradise Inn Annex (2019) were rehabilitated to ensure their continued use into the future while still preserving their historic character. New exhibits and facilities incorporated better accessibility standards so visitors of all abilities could utilize them. At Carbon River, a new ranger station, located in a remodeled property just outside of the park’s entrance, opened in 2013. Designated use areas for tribes were established in 2015 at Longmire for the Nisqually Tribe and in 2016 at Ohanapecosh for the Cowlitz Tribe, part of ongoing efforts to improve co-stewardship with the mountain’s associated tribes. Climate change has been recognized as a growing influence on the mountain’s natural systems and has proved to be a challenge for maintaining park infrastructure. As glaciers melt, they deposit more and more rocky debris in river systems. As rivers fill up, they can change course and damage the historic roads that parallel the rivers. Carbon River Road to Ipsut Creek Campground washed out numerous times in the park’s history and was finally closed to vehicles after the November 2006 flood. As glacier’s retreat, exposing even more unstable rock higher on the mountain, debris flows are expected to become more frequent. Park scientists also monitor the mountain’s glaciers, rivers, meadows and forests, tracking how ecosystems may change in a changing climate.

NPS Photo Throughout its history, Mount Rainier has varied widely in its significance and benefit to its visitors. The idea of what the area can and should be, has changed dramatically and will continue to shift. These changes are particularly evident in the century since Mount Rainier became the nation’s fifth national park. The park is no longer home to a health spa and golf course, but the core values of enjoyment and preservation continue to drive its existence. As Mount Rainier pushes into the 21st century, park management faces a challenge balancing the competing meanings of the area with increased use. But if its history is any guide, the park will adapt to new challenges and continue to preserve the mountain as a place of wonder and amazement.

|

Last updated: August 19, 2024