NPS The Chilkoot Trail has served as a travel route for thousands of years. First used by the coastal Tlingit to trade with people in the interior, the trail became famous during the Klondike Gold Rush as one of two routes from the Lynn Canal to Lake Bennett, the headwaters of the Yukon River. Today, the Chilkoot is a recreational hiking trail and 33-mile-long outdoor museum lined with artifacts from its illustrious past. Some of our park's most valuable cultural resources are located along the trail and have been preserved by favorable environmental conditions. As our climate warms, conditions that have been stable are beginning to change. A warmer, wetter climate presents a number of threats to archeological resources; these factors build upon one another, intensifying their effects and destroying sites faster. Archeologists must adapt and find new ways to cope with these changes to ensure valuable resources are not lost forever. Continue reading to discover threats to cultural resources and how archeologists are dealing with them

NPS photo Early Snow MeltHistorically, the summit of the Chilkoot Pass was covered with snow for ten months out of the year, which allowed the preservation of organic Gold Rush era materials like leather and canvas. Increased warming in the winter and summer months is now causing snow to melt off earlier, exposing artifacts to conditions that cause decomposition and decay. A warmer and wetter climate will destroy organic artifacts that have long been preserved in snow and ice near the scales and summit of the Chilkoot Pass. Previously considered stable, archeologists will now have to closely monitor these artifacts to assess the impacts of the warmer weather. The park will either remove the artifacts for conservation or leave them in place and document them as they decay. While it is unfavorable to allow these materials to decompose, collecting and storing the artifacts is costly and removes them from the trail where they are accessible to the public.

NPS photo Melting Ice PatchesThere are over 250 ice patches located within the boundaries of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. Ice patches, which form over time as snow accumulates and is compressed into ice, have excellent qualities for preserving artifacts. Unlike glaciers, which move once they gain enough mass, ice patches are stationary and preserve artifacts in context. Instead of being crushed or deformed by moving glaciers, artifacts embedded in ice patches are kept in near-pristine condition until the ice melts.

NPS photo The warming climate in southeast Alaska causes both decreasing winter snow accumulation and increasing summer ice patch melting, resulting in the shrinkage, or even disappearance, of ice patches. This is a catch-22 for archeologists, because though melting ice reveals new artifacts, it also exposes them to harmful atmospheric elements. In 2016, park archeologists began surveying ice patches on the Chilkoot Trail to determine if they contained archeological materials and to document and preserve any cultural resources that had emerged. The melting of the ice patches will continue to be monitored over time to provide insight into the changing climate and to assess how these changes are impacting archeological sites.

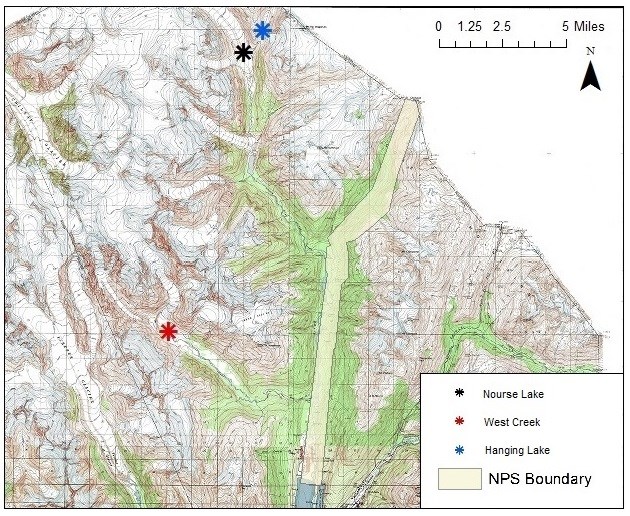

NPS map/C. Rankin Glacial Outburst FloodsLocated in the mountains along the Chilkoot Trail are several pro-glacial lakes. These lakes are formed by glacial melt water and are often dammed only by earthen materials, sometimes containing an ice core. The failure of these dams could result in glacial outburst floods, which would inundate the trail and wash away archeological sites. Climate change is pushing the risk of glacial outburst floods to critical levels; the warming climate melts the ice-cores of lake dams, which can lead to the failure of the dams, and causes glaciers to retreat, which increases lake water volume. Three pro-glacial lakes along the Chilkoot Trail have the potential to destroy archeological resources. One of them, Nourse Lake, poses particularly catastrophic consequences because a flood could impact four significant Gold Rush sites: Canyon City, Finnegan's Point, Kinney Bridge, and Dyea. These sites must be thoroughly documented to ensure data is not lost in the event of a flood.

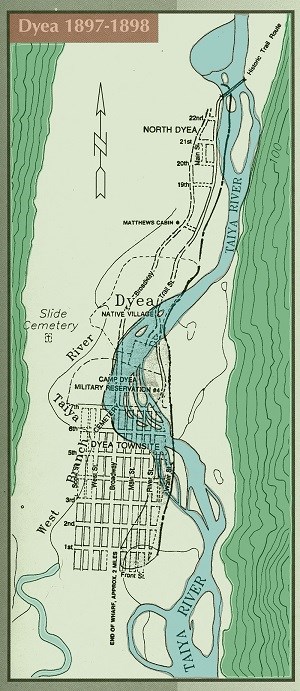

NPS map River Channel InstabilityIn some cases, the changing climate causes rivers to become unstable. The Taiya River, which runs along the Chilkoot Trail, has shifted in recent years, threatening the archeological sites associated with the trail. The shift in the Taiya River's course was caused by glacial rebound, the rise of land that was once depressed by glaciers. The rise in elevation in the river valley, approximately six feet since the Gold Rush, caused the river's base level to change. The head of the Chilkoot Trail, Dyea originated as a seasonal Tlingit village and grew to a boomtown of up to 8,000 people during the Gold Rush. The Taiya River has eroded the northern end of the town site, washing away the majority of Camp Dyea, which served as Gold Rush era military grounds, and much of the native village. There, the changing course of the river has been monitored since the 1970s. Not far from Dyea is the Kinney Bridge, which historically connected the first few miles of the Chilkoot to the rest of the trail on the opposite side of the river. In 2011, archeologists noticed the Taiya River was eroding the site of Kinney Bridge and excavated the site to save the information before it washed away. Today the river continues to erode Kinney Bridge at an average rate of 2-4 meters each year. Though stabilizing the Taiya River was considered, it was rejected due to high costs and potential negative impacts on natural resources. Instead, archeologists will continue to monitor and document these sites closely. For More InformationThis page was adapted from a brief written by Caitlin Rankin, George Melendez Wright Young Leaders in Climate Change intern at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in 2016. Read more about archeological work at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. Discover additional ways the National Park Service is adapting to Climate Change. Or browse more articles about the intersection between archeology and climate change. |

Last updated: August 6, 2024