|

Discovery On July 16, 2001, during a routine whale survey, park biologists discovered the bloated body of an adult female humpback whale floating "belly up" near the mouth of Glacier Bay. The next day, her 45-foot long carcass was towed to the shore near Point Gustavus.

NPS

NPS Photo Once on the beach, park biologists examined the carcass more closely and noted extensive bruising near the left eye. This prompted questions regarding time and cause of death. Six days later a more thorough examination by marine mammal veterinarian, Dr. Frances Gulland, revealed multiple compound fractures at the base of the skull, indicating a collision with a large cruise ship. During the necropsy, several fetal bones were also found in the whale's peritoneal cavity, indicating she was probably four or five months pregnant when she died. Numerous biological samples were taken to help determine age, genetic relatedness to other whales, sex, and diet.

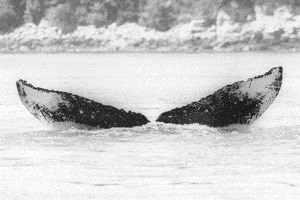

Jurasz Photo Who Was Whale #68? Park biologists very quickly were able to identify the dead whale by using photo identification. Much like a fingerprint, humpback whales have distinct markings on their tail flukes that identify them as unique individuals. Using a catalog of fluke photographs compiled by whale biologists, the park was able to identify this individual as Whale 68, aka "Snow.". Often seen throughout Southeast Alaska and Hawaii, she was first photographed in Glacier Bay by pioneer researcher, Charles Jurasz, in 1975. Jurasz nicknamed her "Snow", presumably because of the white dots on her flukes.

What We Learned Though Snow's death was untimely, she contributed much to science. Between 1975 and 2000, she was sighted throughout southeastern Alaska and Hawaii. Because she had such a long sighting history, she was quite valuable to studies of humpback whale life history in the North Pacific. Not only was she long-lived, but may have also contributed to the growth of the population of this endangered species. She was likely the mother of at least 10 offspring and (assuming that at least half of those were female, the grandmother of an additional 10 calves. Skin samples were collected at the time of death to help biologists determine genetic relatedness of humpback whales in the North Pacific. Through DNA analysis, biologists can genetically match Snow to other whales that may share similar DNA. By using 67 sloughed-skin samples previously collected during whale monitoring studies, they may even be able to identify some of Snow's offspring. Many other samples were taken (blubber and stomach contents), but none quite as significant as the earplugs. They helped put a long controversial debate to rest. What is an earplug? The earplug of a humpback whale is essentially a layered piece of wax that accumulates over the whale's lifetime. And just like a tree, a whale's age can be determined by counting the layers of wax like the rings on a tree. However, there was much debate over whether a humpback whale earplug accumulates one or two layers of wax per year. For example, if you see 20 layers does that mean the whale was 10 or 20 years old when it died? By using Snow's sighting history and the data from her ear plugs, biologists were able to confidently conclude that one growth layer is deposited annually and that Snow was 44.5 years old when she died.

Learn more about Whale 68: |

Last updated: September 8, 2016