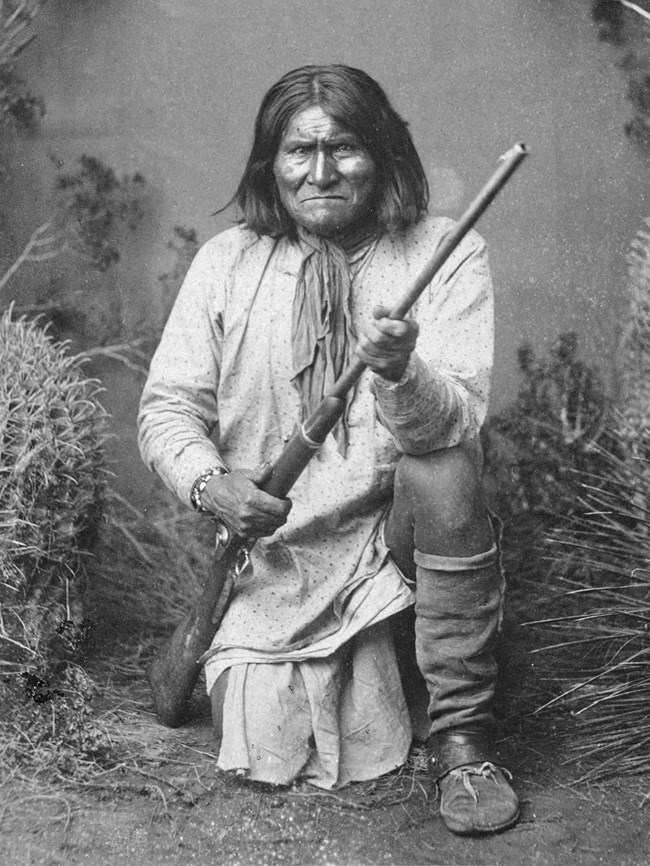

Public Domain/US National Archives, Ben Wittick, 1887 Geronimo was born on the Gila River in New Mexico, not far from the Gila Cliff Dwellings. His birth name, Goyakla, meant "one who yawns." He would go on to become a brilliant war leader. While Cochise was a noble leader, Geronimo was more of a rogue. As a young man, Geronimo had lost one of his wives, some of his children, and his mother to a massacre carried out by Mexican soldiers. He would never forgive the Mexican people for this nor forget his hate for them. Geronimo felt he had little purpose after this event. One night, atop Bowie Peak, he heard Ussen’s voice on the wind say to him, “You will never die in battle, nor will you die by gun. I will guide your arrows.” Geronimo believed this to be true for the rest of his life, and for good reason. He petitioned to Chief Cochise and Chief Mangas to campaign deep into Mexico to avenge his family’s death. Geronimo told them he would lead the battle as he did not care whether he lived or died. It was during this campaign that Geronimo would get the name he is known by today. During the battle, Geronimo did not fire arrows from cover as many of the other Apache did. Instead, he ran zig-zag at the Mexican soldiers so as not to be hit by their bullets. He would then kill them with a knife and take their rifles back to other Apache warriors, as he did not know how to use a rifle at this point. The Mexican soldiers began to shout "Geronimo!" to warn each other of his charges. The origins of this word are still unknown. The Chiricahua Apache began to chant the name in enthusiasm and intimidation. Geronimo was a complicated man. Many Americans at the time dubbed him as “the worst Indian that ever lived.” He was quick-tempered and paranoid; nervous, but very, very lucky. He was deceitful and cruel, prophetic and brilliant, ambivalent and even sometimes a little sheepish. His contradictory yet effective nature makes him one of the most fascinating characters of the Apache Wars.

Public Domain/ New York Public Library, Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection, American History 1880s, C.S. Fly Geronimo’s First EscapeJohn Clum, agent of the San Carlos Reservation, struck a deal with Juh and Taza, who had taken his father's place as chief. Juh and Taza agreed to gather their people and things, scattered throughout the now disintegrating Chiricahua Reservation, and move to the San Carlos Reservation. Geronimo instigated a disagreement between the leaders. Only one third of the Chiricahua went with Taza to the San Carlos. Two thirds followed Juh and Geronimo off the reservation, thus breaking the deal with Clum.After arriving at the reservation, Taza ended up taking a trip to Washington, D.C. to learn about the ways of the white man. While there, however, he got sick and died. Chieftainship passed to his younger brother, Naiche, who Cochise had not groomed to be a leader the way he had Taza. Geronimo’s First CaptureThe broken deal infuriated Agent Clum. He received word that Geronimo was the instigator of the broken deal, and that he had made it all the way to the Ojo Caliente Reservation in New Mexico. Clum set out for the reservation at once. Geronimo must have not realized what danger he was in at the time. Geronimo was easily outsmarted and captured by Clum at the Ojo Caliente Reservation. This was due mostly to the Apache scouts who had betrayed him. Clum took Geronimo back to San Carlos where he hoped to put him to death, but Geronimo’s luck ran deep.Back in Washington, D.C. the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of War were still fighting over jurisdiction of the Chiricahua Apache. They could not reach a decision on Geronimo’s fate. Clum was furious as Geronimo sat in shackles before his release. Geronimo stayed on the San Carlos Reservation for a few days, however. He decided to leave before his sentence could be finalized. Clum resigned shortly after Geronimo's escape. Chief VictorioWhen Geronimo was captured on the Ojo Caliente Reservation, he accidentally brought the attention of the U.S. military to the Warm Springs band of the Apache who were living on the reservation at the time. They were led by Chief Victorio. The Ojo Caliente Reservation was closed, and Victorio and the Warm Springs band were ordered to move to the San Carlos Reservation, which they knew was far inferior to Ojo Caliente. Victorio and the Warm Springs band escaped in the night. An order was made, stating that any Chiricahua found off reservation was to be killed. The Warm Springs band were pursued across the Southwest and into Mexico fighting furiously the whole time. They were eventually killed by Mexican soldiers. Victorio was said to be the last one standing.

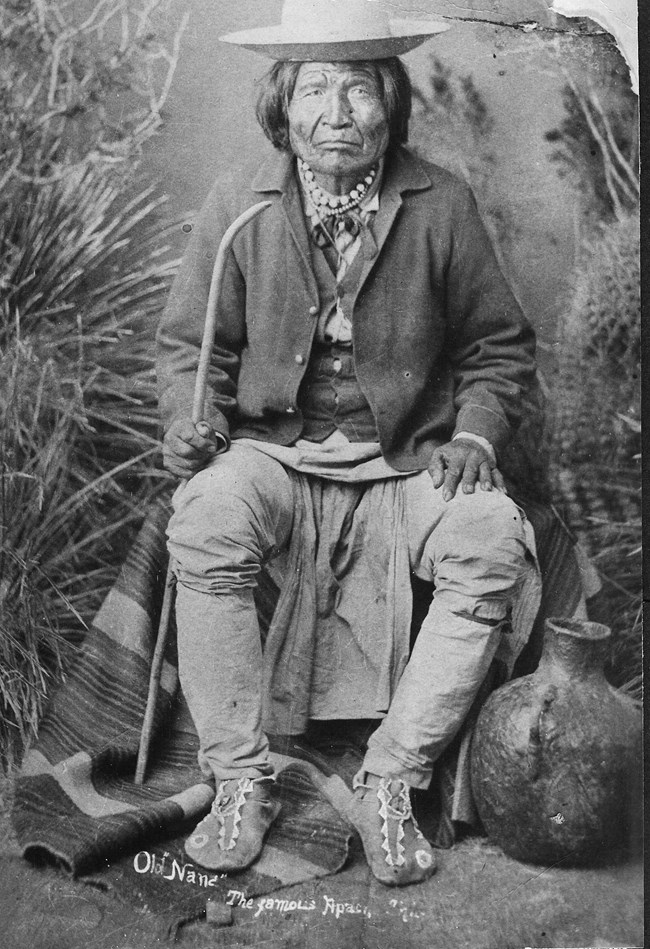

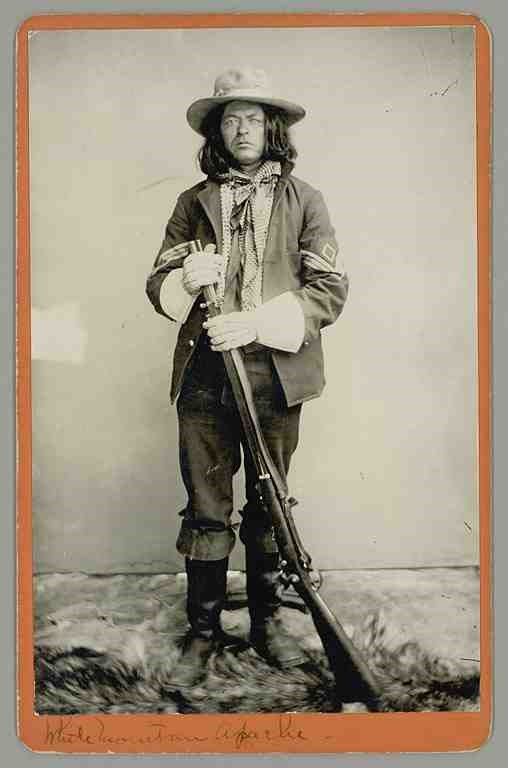

Public Domain/US National Archives, Ben Wittick The Chiricahua Apache GatherDeep in the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico, in a place called Juh’s Stronghold, the Chiricahua Apache were beginning to gather in the largest numbers since the time of Cochise. Great warriors came, including the ironically named Fun, perhaps the best warrior of the group. Once Fun found himself surrounded by seven Mexican soldiers with only a bush to hide in. He killed each soldier with a bullet to the head and escaped with his life. Lozen, the famous woman who gave up a life of marriage to become a warrior, attended as well. There were also Chief Chihuahua and Chief Nana. Nana was a brilliant and shrewd leader who led some of the most successful raids even at 75-years-old.The Chiricahua hid caches of food and supplies across much of the Southwest and Mexico. Geronimo trained young warriors. He despised the leaders of his people who gave up easily or made choices that led to their capture or death. Geronimo even went so far as to force Chief Loco and his band to depart the San Carlos Reservation at gunpoint, and it was a grueling journey. The Chiricahua at this point numbered around 600; half of what it had been at the beginning of the war in 1862. Juh unfortunately fell off his horse and died. The Tan WolfGeneral George Crook returned to fight the Apache once again. His nickname, the Tan Wolf, came from the khaki-colored civilian clothing he wore. Chief Nana saw his return as good because he was a "good enemy." Like Nana, Crook also had a strong respect for his enemy. When asked about the Chiricahua Apache he said, “Acuteness of sense, perfect physical condition, absolute knowledge of locality, almost absolute ability to persevere from danger. We have before us the tiger of the human species.”Geronimo’s notoriety as a successful Chiricahua leader had grown. Crook knew that finding Geronimo would now be the key to U.S. victory. Crook set out with both Apache scouts and U.S. soldiers to do just that. Foray into Mexico The Chiricahua continued to raid in both the United States and in Mexico. The Mexican people began to believe that Geronimo was the devil come to punish them for their sins. The U.S. and Mexico continued to track, capture, and kill Chiricahua Apache when they could. Deaths continued for both sides. The U.S. and Mexico struck a deal that they could cross each other’s borders in pursuit of the Chiricahua. The United States and Mexico had been at war only decades earlier, however. The deal was a shaky one at best, as Lieutenant Emmet Crawford would find out. He was able to track Geronimo and his band down in Mexico. Before Crawford could confront Geronimo and his band, Mexican soldiers, unaware of Geronimo’s nearby whereabouts, accused Crawford of breaking the border deal. Crawford tried to reason, but the Mexican soldiers shot and killed him. Treachery was likely involved. Geronimo was rumored to have been sitting on a nearby hill, watching the events unfold, and laughing. Crook ChargesGeneral Crook was hot on the heels of Crawford and was able track Geronimo down not long after Crawford’s death. Crook wanted to enter negotiations, but things were too tense at first. After a short skirmish, Geronimo and his band sat on a cliff above Crook’s company exchanging taunts with Crook’s Apache scouts. They entered into negotiations in a way no one could have predicted. Crook was a compulsive hunter, and the next day he wandered off on his own tracking an animal. Before long, he found himself alone face-to-face with Geronimo and some of his best warriors.Geronimo didn’t kill Crook. He had found the same truths about life on the run as Cochise before him. The U.S. was too well-supplied, and had what appeared to be an endless number of troops. Constant vigilance and hiding was no way to live. The Chiricahua were of a low morale and wanted to enter negotiations. The Chiricahua respected Crook, and after some deliberating, they struck a bargain that the Chiricahua would move to a new reservation called Turkey Creek. Lieutenant Britton Davis became the agent.

Public Domain/ Library of Congress, C.S. Fly 1886

Public Domain/Charles Gatewood Turkey Creek: A New ReservationThe war once again entered a peaceful period, however this one only lasted a year. Agent Davis tried to get the Chiricahua to farm. It was popular belief in the U.S. at the time that Native Americans would have to assimilate to the ways of the white man to survive.Davis made it law that Chiricahua men could no longer beat their wives which within their culture was their right. Davis also made it illegal for the Chiricahua to brew the alcoholic beverage called Tizwin. One Chiricahua man was even sent as far away as Alcatraz for breaking these laws. Unrest began to slowly brew on the reservation. It reached a boiling point as Apache translators began sowing seeds of tension between the Chiricahua and Agent Davis. One of these scouts was Mickey Free, who was once known as Felix Ward. He was the very same boy who had been kidnapped from John Ward’s farm in the raid that caused the Bascom Affair. Mickey was raised by Apache scouts but showed little allegiance to either the U.S. or the Apache. Mickey had been an Army scout and later an Apache scout. He understood both English and Apache, though imperfectly, so he served as a translator. Translations around this time were often more complex than English directly to Apache. Translations would often have to go from English into Spanish into Apache and vice versa. Miscommunication ensued. Geronimo eventually heard a rumor that he was going to be arrested. He decided to instigate another breakout. Davis wired Crook, but it was too late. Carnage followed in the wake of the Apache escape from Turkey Creek. The Final RunMost of the Chiricahua remained on reservations this time. The remaining free Chiricahua took up hiding once again in the Sierra Madre Mountains. Crook pursued Geronimo into Mexico one last time. When he found him, Crook was upset with Geronimo for breaking all of their deals. Geronimo pleaded that he wouldn’t have broken the deals if he hadn’t heard that he was going to be arrested. Crook was not able to offer the terms of surrender that he was able to before. Geronimo knew his cause to be hopeless and surrendered once again.Crook left for Fort Bowie, leaving the Apache removal in the hands of Lieutenant Marion Maus. That same night, Geronimo and his band bought whiskey from a Swiss bootlegger named Robert Tribolet. Tribolet supposedly profited from the Apache Wars and thus sought to perpetuate the war. He told Geronimo that, upon returning to Arizona, he would be hanged. In the days to come, in a drunken stupor, the Apaches escaped and broke the terms of their surrender. General Crook wanted Tribolet dead. A New General Takes ChargeAfter this last failed surrender, General Crook contacted President Grover Cleveland. Crook told him he still wanted to offer the Chiricahua terms for their surrender. Cleveland rejected this, stating that the surrender needed to be unconditional. Crook disagreed with this method and felt that his way would bring about better results. Crook resigned and was not looked upon favorably afterwards.A $25,000 bounty was placed on Geronimo’s head and a new general took over: Nelson Miles. General Miles would earn little respect from the Chiricahua Apache. Unlike Crook, Miles lead from faraway forts. Miles also came up with a shrewd and cruel idea that would bring about a final Chiricahua surrender.

Public Domain/US Army Military History Institute, Caroline Thurber 9,000 vs. 37Fear gripped the Southwest during the final summer of Chiricahua freedom in 1886. Geronimo led through Naiche, who was still chief. The final free band of Chiricahua numbered only 37. They included 18 warriors, 13 women, and six children including two infants. They remained at large for five months while around 5,000 employees of the United States Army (a quarter of the force) were stationed in the area to track the Apache. Around 3,000 Mexican soldiers and a little less than 1,000 volunteers were also put to the task.Some of the women and children in the final Apache band surrendered as the summer wore on. The band only experienced one death that whole summer. Many U.S. soldiers found conditions in the Southwest during summer to be unbearable. Meanwhile, Geronimo was more reckless than ever. He felt it was the best fighting the Apache had ever done. He was also said to have trusted in his powers more than ever. When a Chiricahua encampment was found, he was supposedly able to intuit the situation from miles off. The Chiricahua spent most of their time during that summer in Mexico. The last six years of the war had cost the lives of 319 Americans and 682 Mexicans. Miles’ IdeaThere were still 434 Chiricahua living on the San Carlos Reservation. Miles’ idea was to banish all of them to prison thousands of miles away in Florida. The free Chiricahua remaining had close family members in this group. Miles hoped that knowing they would never see their families again without surrendering would cause a final Chiricahua Apache surrender.SurrenderLate that summer, Lieutenant Charles Gatewood pursued Geronimo and his band deep into the Sierra Madre. At a place in the mountains called Bavispe, he knew he was closing in. Gatewood sent two Apache scouts forward who some of the free Chiricahua band had personally known. The scouts told Geronimo and his band that the rest of their people, including their families, had been sent thousands of miles away. This had the intended effect. Geronimo held a conference with Gatewood and agreed to surrender.“Once I moved about like the wind. Now I surrender to you and that is all,” Geronimo said. Continue the story of the Chiricahua Apache after the surrender. |

Last updated: August 19, 2018